Fifteen days and nights of continuous sunlight, followed by 15 days and nights of continuous darkness. Passing meteorites that frequently strike the ground and kick up debris. Radiation unfiltered by any sort of atmosphere. One-sixth of the Earth’s gravity, no air pressure to speak of, and persistently occurring moonquakes.

On the moon, the environment is extremely harsh, there’s no atmosphere, and it’s a hard vacuum; the temperature fluctuates in the extreme, and it is under continuous exposure to a deadly level of radiation. — Ramesh Malla

The environmental conditions on the surface of the moon are harsh, to say the least, making NASA’s goal of returning and staying on the moon by 2024 a challenge for scientists and engineers.

UConn researchers, though, will be on the front line of the effort, through a new NASA-funded project aimed at advancing the design of resilient, deep-space habitats.

A team from UConn – in a partnership led by Purdue University and including Harvard University and the University of Texas at San Antonio – was recently selected to be a part of a new Space Technology Research Institute (STRI). The institute’s goal is to help mature the mission architecture needed to meet NASA’s challenging goals of creating a sustainable human presence first on the moon, and later on Mars or possibly other planetary bodies, like other planets, moons, or asteroids.

“On the moon, the environment is extremely harsh, there’s no atmosphere, and it’s a hard vacuum; the temperature fluctuates in the extreme, and it is under continuous exposure to a deadly level of radiation,” says Ramesh Malla, a professor of structural engineering and applied mechanics in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at UConn’s School of Engineering, who is leading UConn’s team on the NASA project.

“When you build a human habitat in such an extreme environment, engineers face a great many challenges,” Malla says. “Materials will behave differently in this extreme temperature fluctuation. Not only that, you really have to worry about radiation, and there is continuous danger of micrometeorite impact. Our purpose is to come up with habitats to survive in this kind of situation, this kind of extreme environment. We’ll be looking to build resilient habitats, where if there is some disruption, it can maintain critical functions and quickly come back to its original operational condition.”

A disruption could be internal – such as an instrumentation or life support malfunction – or external, like a meteorite strike that punctures the structure of the habitat, Malla says.

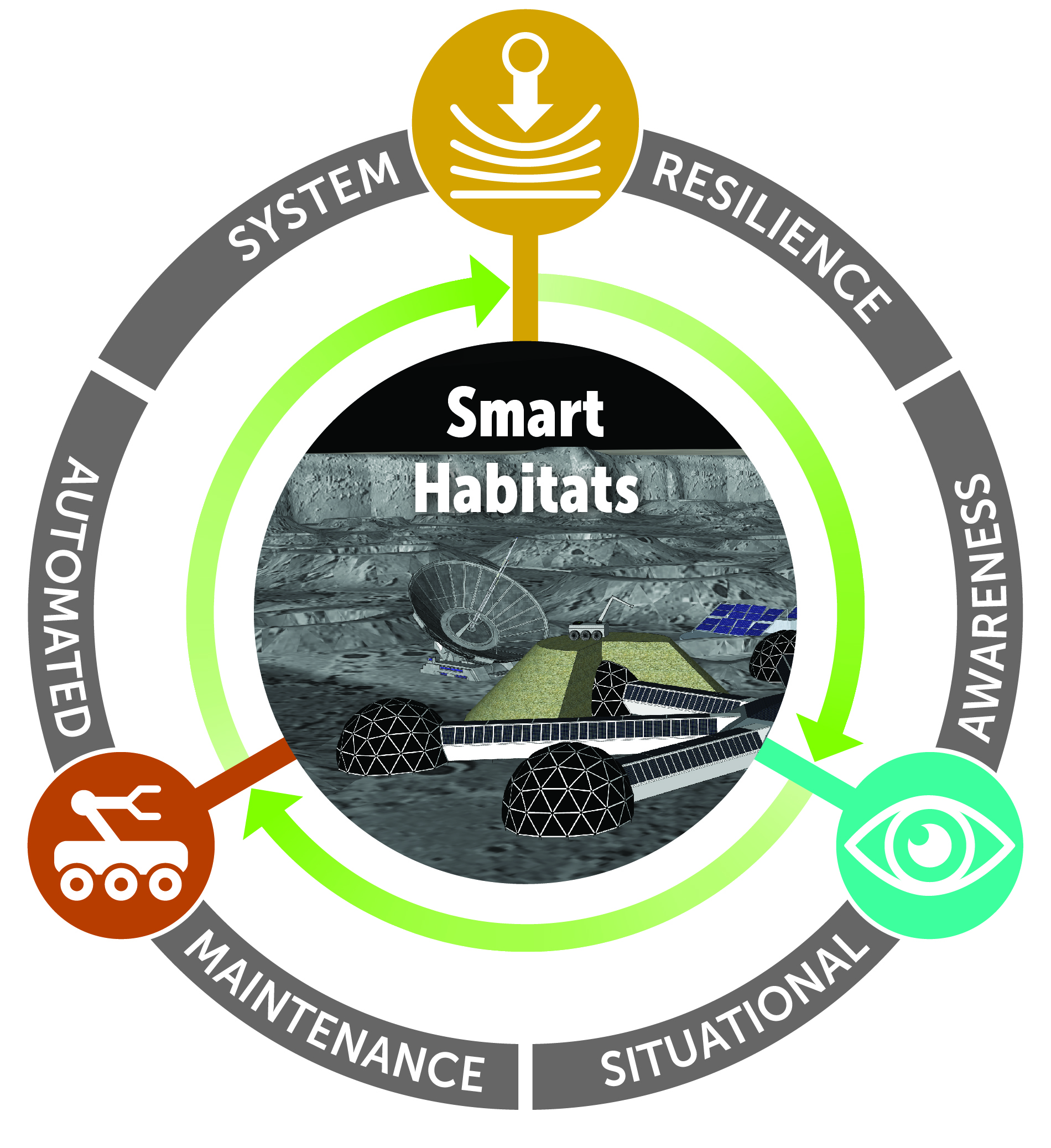

The UConn team will take part in the Resilient ExtraTerrestrial Habitats institute (RETHi), which will seek to design and operate resilient deep-space habitats that can adapt and recover from expected and unexpected disruptions. The new institute will receive as much as $15 million over a five-year period to fund its work of designing and ultimately creating a prototype of an autonomous, resilient, deep-space habitat that is capable of functioning with and without the presence of a human crew.

“As NASA works toward its goal of returning to the moon,” says Radenka Maric, vice president for research at UConn and UConn Health, “UConn researchers are at the forefront – developing the resilient technology to allow greater space exploration and human habitation beyond our planet.”

UConn researchers are expected to receive approximately $3.25 million for their work. Malla says his team will be involved in all aspects of the project, which will focus on three main areas: smart design, growth and architecture; context-based situational awareness and intelligent health management; and autonomous robotics for operation, maintenance, and recovery.

“UConn has a truly multidisciplinary team contributing on all aspects of the project,” he says. “Bringing all these different areas together, really seamlessly connecting them to a particular project, is going to be an interesting, enriching experience, and challenging all at the same time.”

Led by Malla, UConn’s team of faculty researchers includes Ashwin Dani, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering; Song Han, assistant professor of computer science and engineering; Krishna Pattipati, Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor and UTC Chair Professor of Systems Engineering in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering; and Jiong Tang, professor and director of graduate studies in the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

Malla, who has been involved with space structure work for more than 35 years, is an Elected Fellow of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) and Associate Fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), and also currently serves as chair of ASCE Aerospace Division’s Technical Committee on Space Engineering and Construction. He played a key role in securing funding and establishing the NASA-sponsored statewide Connecticut Space Grant College Consortium in 1991, and served as the founding campus director of the Consortium from UConn for the first nine years.

UConn President Susan Herbst says the project is “an exciting, collaborative opportunity that recognizes the expertise and experience that our UConn faculty have to offer. UConn’s team will be contributing to all aspects of this project, which has important and broad implications for space research both in the United States and internationally.”

Adds Kazem Kazerounian, dean of UConn’s School of Engineering, “This project is one in a long line of strategic research projects we have embarked on. Our inclusion in this project speaks to the strength of our faculty, and the track record of our research in this field.”

The RETHi project also aims to accomplish more of NASA’s key objectives: Educating the next generation of engineers and scientists, building partnerships with U.S. industries and organizations and other nations, and generating research knowledge that will inform and guide future research and development. UConn’s team plans to engage UConn undergraduate and graduate students, as well as postdoctoral fellows, in the project. The institute currently has two industry collaborators: Collins Aerospace, a unit of United Technologies Corp.; and the engineering and manufacturing company ILC Dover.

The project is funded by NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate, which is responsible for developing cross-cutting, pioneering new technologies, and capabilities needed by the agency to achieve its current and future missions.

For more information, visit nasa.gov/spacetech.