“Your cap is a passport,” the nurses were told, as they were recruited from their home in the Philippines to work at hospitals in the United States and around the world – a reference to the starched dresses and caps worn by nurses that have since fallen out of fashion as well as the recognition and dignity placed on that ubiquitous white uniform.

About one third of all foreign-born nurses in the United States are from the Philippines, and since the 1960s, more than 150,000 Filipino nurses have migrated to the United States, bringing Filipino culture with them and establishing a legacy of care in this country. A new exhibit on display now through the end of the year at UConn’s School of Nursing pays tribute to the work of Filipino nurses through stories and original art pieces that incorporate elements of Filipino migration stories and their political and social history.

“Filipino nurses are a vital part of U.S. health care, and they have overcome enormous obstacles to be that,” said Jason Oliver Chang, director of UConn’s Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, who wrote and produced the Filipino nurses’ exhibit in collaboration with School of Nursing Professor-in-Residence Thomas Long. The exhibit features the path-breaking scholarship of Ethnic Studies historian, Catherine Ceniza Choy, of the University of California, Berkeley, who also served as a consultant for the project.

“Asian Americans have been integral to different parts of the workforce, and have been integral to health care, for basically a century,” said Chang, “but that’s not something that always gets recognized. I wanted underrepresented nursing students be able to see themselves in the history of the profession. The Filipino Diaspora is such a large part of the nursing world, but it is often invisible. People like to say it’s hidden in plain sight, so I wanted to give voice to that.”

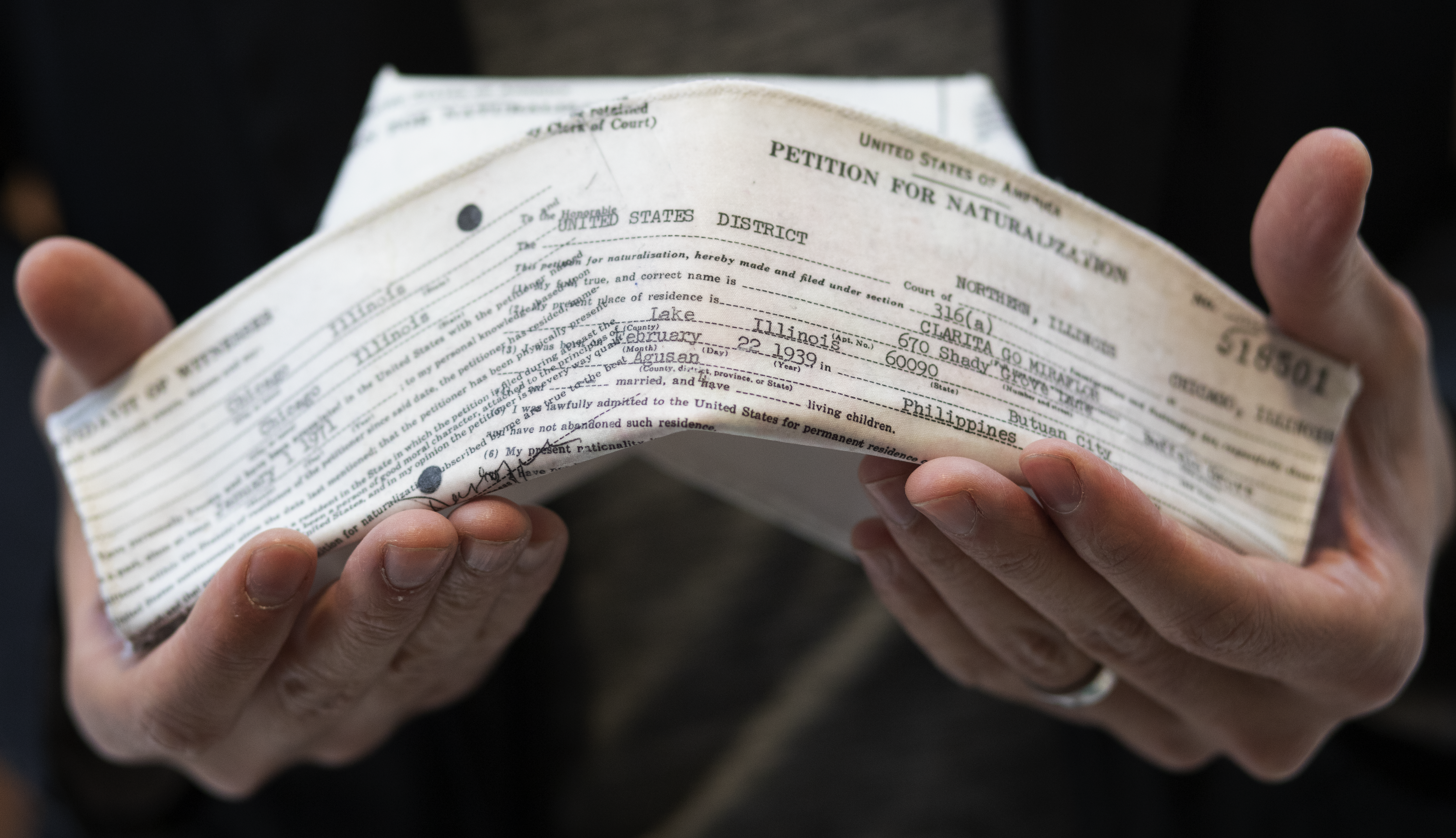

The exhibit highlights facts and statistics about the contributions of Filipino nurses in the American health care system and tells the story of Dr. Clarita Go Miraflor – a Filipino nurse, researcher, author, and founding president of the Philippine Nurses Association of America. A handmade nurse’s cap featured in the exhibit, commissioned from Manhattan-based Filipino American artist Jeanne F. Jalandoni, is imprinted with ripped and repeated layers of Miraflor’s naturalization form – “an echoed declaration to demand the visibility and respect of Filipino nurses around the world,” according to the artist’s statement.

“I wanted to be able to draw from Filipino voices,” Chang said of his decision to focus on Miraflor. “She epitomizes the strength of Filipino women in the nursing field as a nurse, as a researcher, as an organizer, and as someone who really throughout her career identified the ways that Filipinos were being discriminated against within the health care industry.”

The exhibit also features a second textile commission from Jalandoni: a stylized nurses’ uniform that combines a variety of fabrics and hand-weaving techniques with the iconic symbol of Filipino fashion, the terno sleeve. The dress bears a red cross on one sleeve, inspired by a 1919 photograph of Red Cross Filipina nurses wearing traje de mestizas – sometimes referred to as the Filipiniana dress or Maria Clara gown – posing in front of the American flag during the period of U.S. occupation of the Philippines. The fabrics woven through the dress are floral, representing family; sheer, representing elegance; satin, representing respect; and batik, for Philippine roots.

“Once woven together,” Jalandoni wrote, “the fabrics mimic the DNA strands of a Filipino identity.”

Chang said that Jalandoni’s pieces are the “real gem of the exhibit,” drawing on a long history of uniforms and attire that characterized Filipino nurses but also gave credit to Filipino culture.

“One of the things that struck me about the nursing uniform is that it’s so standardized that it has a way of erasing heritage,” said Chang. “It comes from a long tradition of being professionals, being credentialed, and having the uniform as a symbol of their training and of the respect that it draws from. But it also is a way of erasing heritage and ethnicity. As a part of a lived experience and a struggle for equity and justice, the uniform helps to expose that long history in a way that just reading a narrative alone wouldn’t.”

While the exhibit will live in the School of Nursing throughout the end of this year – part of the school’s celebration of the World Health Organization’s designation of 2020 as the Year of the Nurse and Midwife – Chang already has plans to replicate the exhibit, with his next stop being the Bulosan Center for Filipino Studies at University of California, Davis, and hopes to work with other UConn schools and colleges to highlight the work of Asian and Asian American professionals and researchers in their fields.

Chang said that changing demographics in Connecticut and across the country, including increasing Asian immigration, will continue to highlight the importance of cultural studies not only in the humanities but also in professional fields, like nursing.

“I want to be able to build recognition for the contributions of Asian Americans and show the kind of obstacles that they’ve overcome in order to do public work,” he said.

“Filipino Nurse Diaspora: Culture, History, and Migration” is available to view in the UConn School of Nursing’s Widmer Wing in Storrs Hall. To learn more about the work of Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, visit asianamerican.uconn.edu or follow the institute on Twitter at @UConnAAASI.