Hayley Stefan is a doctoral candidate in English and a Humanities Institute Dissertation Research Fellow who is focusing her research on the growing genre of school shooting fiction. Her dissertation is titled: “Writing National Tragedy: Race & Disability in Contemporary U.S. Literature and Culture.” From her dissertation research, she has established The School Shooting Fiction Archive, which investigates school shooting fiction. The archive currently includes 76 school shooting fiction texts published between 1977 and 2019, with more than half published after the shootings in Sandy Hook in December, 2012. She spoke with UConn Today about her research.

You have come to a very contemporary and serious subject with high school shootings. How did you decide that was what you were going to focus your scholarly research on?

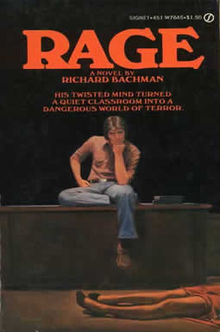

I grew up in a family of funeral directors. We spent our sick days, family meetings, around other people’s trauma. During my research, I kept coming across that idea of the flashbulb memory, the recalling of where you were when you learned about something. For a lot of people in my generation, it’s 9-11. For my students, it seems to be more Sandy Hook and the Boston Marathon bombing. While I continued doing my coursework and research, I kept coming across these books, starting with Stephen King’s “Rage,” and I kept thinking: there’s got to be something here. There are more and more of these books being published.

When did you begin to figure out what you wanted to examine?

When I first started teaching for college, my first class was at Worcester State University. It was right after the Sandy Hook shooting and I decided to teach Stephen King’s short essay “Guns.” In that essay, he talks about pulling his book “Rage” from publication in the ‘90s because three or four shooters quoted from the book or re-enacted it in real shootings. As I kept researching for my dissertation, I kept finding more and more of these books. After a while, my dissertation committee said, look, you can’t write about 76 books. So I chose Stephen King’s “Rage” from 1977 written under his pen name, Richard Bachman, and Jodi Picoult’s “Nineteen Minutes” from 2007. The digital archive grew out of the rest.

The digital archive is a collection of the information about these books. What does this include?

Pathologies of Mad Violence, a School Shooting Fiction Archive is a collection and a listing of those 76 books, dating from 1977. Other lists of school shooting books have included nonfiction as well as fiction. This is the first archive that looks specifically at how these events are fictionalized. I also bring together research on what these books are doing, how they’re using these different ways of setting up the novels, using flashbacks and flash forwards, and how they’re using specific language about race and mental disability to tell us a bit about the assumptions we have about gun violence. What I hope that the archive does is add to that by bringing educators, librarians, and readers into the conversation so they can make educated choices about what kinds of books they’re reading and what kinds of books they’re advocating for others.

These books often are aimed at a young adult audiences. What do you think about the marketing of these books to that audience?

It’s absolutely fascinating. A lot of the books kind of give us what I call a chronology of mad violence. They follow the shooters across their lives, suggesting that it was inevitable this shooting was going to happen; all of the moments that they were acting crazy in the past or being bullied. What school shooting activists and gun violence activists are doing now is saying that’s not the full story, that what happens when gun violence occurs is much bigger than the conversation around mental illness and mental disability. Realistically, school shootings make up an almost negligible amount of the gun violence that we see in the world, and an even smaller amount of the gun violence fatalities. School shootings tend to happen in areas that we consider to be white, middle class suburban areas, but gun violence occurs much more broadly than that. Gun violence deaths tend to more often affect people who are people of color and disabled people. We start making arguments about who’s crazy and who should be surveilled.

In your presentations and on your website you list some guiding questions for how you’re going about searching for answers to those questions. What are those questions and how are you trying to answer them?

Some of the questions that I’m asking include who’s writing these books, when are they being published, and by whom are they being published? It turns out it’s a lot of white women writing and a lot of smaller presses, though a few of the big publishing houses have picked them. I’m also really asking how these books are recycling these ideas, that madness always leads to violence or that disability always leads to violence, and that the sort of ideal or imagined victim of gun violence is a white child in a classroom. We know that’s not the case, that gun violence affects a much broader audience. I’m asking how these books are continuing to spectacularize the school shooting rather than talk about these larger issues. It makes it more of a school shooting as an individual, spontaneous event rather than a systemic problem about violence, guns, and surveillance.

When starting your talks, you note that the way the discussion about gun violence takes place matters. What do you mean by that?

When we talk about gun violence, we talk about who the people are that are victims. More often than not, our conversations center on who the shooter was, what they were doing in their life and how come we didn’t catch all of the warning signs that this was going to happen? As we see with some of the activists coming out of Parkland, the March for Our Lives activists, this is not the way that gun violence tends to take place. So when we start zooming into that idea of the crazy school shooter, we end up reinforcing ideas that we should be surveilling bodies; restrict movement. It comes back to that “See something, say something” thing about mental illness. The way that our education system and our social systems work now, people of color are much more likely to be read as disabled, distressed, or having an emotional breakdown. What this means is that anytime we put in place policies to surveil or punish those people who are acting abnormal, it exponentially affects people of color much more. But the reality is that people of color and disabled people are much more likely to be victims of gun violence than they are to be perpetrators of it.

“Writing National Tragedies” examines a concept of national tragedies in the United States, multiethnic literature, legal documents, and other cultural artifacts from World War II to the present. What are you trying to do with your dissertation on this topic?

I’m trying to figure out why some events get more attention than others, particularly traumatic events. That ends up being a conversation about whose trauma ends up mattering more. For me, this is a conversation of how that trauma is discussed, whether it’s in the media, political, social coverage, popular culture, or even legislation. All of this brings us back to what we signal is the ideal imagined American. I’m certainly not the first to point out that person tends to be a white, cisgender, heterosexual male who’s able-bodied and financially stable. In my dissertation, I focus specifically on those identity categories of race and disability, how we signal through pop culture, what we write, who we valorize is that ideal person and how all of these coverage of traumatic events can be used by activists and scholars to kind of push for alternative histories and coverage.

You are living in the state where Sandy Hook occurred. Has that energized you a bit more on this project?

I’m from Massachusetts, right over the border. I think being close by, having conversations with my students who either were nearby or had family members who were working at hospitals that helped, it’s been eye-opening. It has motivated me more to want to research this and help out.

What is it that people should know about this issue that would signal what you’re doing is having some sort of impact out in the world?

I would say look to the youth activists. They are the ones directly affected and they’re the ones whose voices we should be listening to. I’m not just speaking about Parkland activists. I’m speaking about young adults like [March for Our Lives activists] Naomi Wadler or Edna Lizbeth Chavez who are fighting for recognition of the violence that affects multiple communities, not just white suburban areas. They’re doing some excellent work, and if my archive can help get that conversation out there, then I’m happy to do so.