What will the new normal look like after COVID-19?

On May 20, many UConn researchers returned to campus laboratories and research spaces as part of the phased reopening of the University and the state.

Now, faculty in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences share what the new normal for UConn researchers looks like, including missed chances, surprising opportunities, and a lot of hand sanitizer.

Currently, over 400 researchers have applied to return to research operations on campus, and about 100 researchers in CLAS have been approved.

For the past five years, Hannes Baumann, associate professor of marine sciences, and his fish ecology lab, have been surveying the coastal fish community at a cove near the Avery Point campus. In the past, Baumann and his graduate and undergraduate students took a shared truck out to the cove, where they deployed a large net, called a beach seine, a few times every two weeks. The lab tracks levels of oxygen and pH in the cove, which means taking out a small boat to service the monitoring sensors anchored in the water. Exploring how coastal marine organisms cope with changes in their environment due to climate change is essential to their research.

Now, the survey must be done with no more than two researchers at a time, and only one person can be in the truck. Before and after they go out on the boat, they wipe every surface with disinfectant, including the life vests.

“Prior to the pandemic, the thought of wiping off the boat before taking it out or disinfecting our old, oily and grimy life jackets, would have seemed comical,” Baumann says.

Julie Fosdick, assistant professor of geosciences, collects data to understand how tectonic and sedimentary processes interact to shape the Earth’s mountains. Though she was allowed to keep her laboratory instruments, two mass spectrometers and a noble gas extraction line, running for maintenance, she will need to recalibrate them before resuming research on the cooling age of minerals from the Patagonian Andes in Chile.

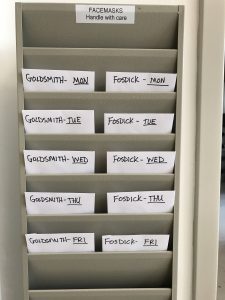

“Protocols include staggering work locations and schedules,” she says, including social distancing and rigorous cleaning. “We have five face masks per person, and will reuse them each five times before replacing them,” she says.

Researchers returning to campus must complete a COVID-19 safety training course based on current CDC guidelines and UConn procedures. But it’s a different playing field for many humanities researchers.

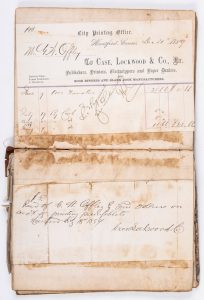

Anna Mae Duane, associate professor of English and American studies, planned to visit Philadelphia this spring to examine the records of the “House of Refuge for Colored Children”—the first juvenile detention center for black children considered “delinquent” in the 1850s. The Philadelphia institution has original records essential to Duane’s research for her next book on child labor and the role of work as redemptive in the nineteenth century penitentiary, which explores the belief that work was both a punishment and path to redemption for people.

One of Duane’s favorite parts of researching archival documents is being able to hold and feel pieces of history in her hands. But the detention center doesn’t have online records, so Duane couldn’t access them during the shutdown.

“I had to change the order [of the book] and put off the chapter on the juvenile prison until later,” Duane says.

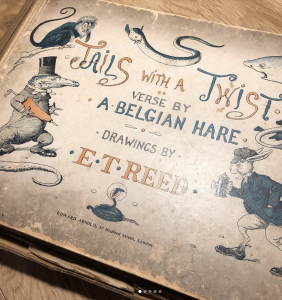

Victoria Ford Smith, associate professor of English, also ended up accessing texts and archives online. Smith needed the book for a near-complete academic article she wanted to publish.

“I was able to purchase one rare book online, although typically I would not spend money to assemble my own archive, but instead rely on library copies,” she says.

Duane attended a video conference with the American Antiquarian Society, a national research library of pre-twentieth century American history and culture, which usually holds in-person meetings.

“I hardly ever get to attend those meetings,” Duane says. “It’s taken us all a little while to figure it out, but there are advantages to [readjusting to virtual work].”

Bernard Goffinet, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, was scheduled to travel the southern United States to examine a species of moss that emerges in early spring. His research focuses on the significance of polyploidy, or having more than two sets of chromosomes, using a moss called common bladder moss.

Though he lost the ability to collect moss, Goffinet saw a chance to engage citizen scientists. He launched an online moss hunt, asking people to collect species across the U.S. Naturalists from 10 states have collected nearly 160 new observations since January.

Baumann recently received tenure, which he says has provided some peace of mind and stability. And though he lost some fish, he made a surprising catch when UConn approved him to visit the cove on May 20.

“For the first time since starting the survey, we discovered juveniles of pollack, an equally tasty but rarer relative of Atlantic cod,” he says. “How fortunate that we got to document this.”

Additionally, he has been organizing a one-day virtual science town hall for June 23 to bring together over 250 scientists across the world whose research touches on climate to exchange ideas.