He was told he had less than six months to live, and he should get his affairs in order. Tumors had reached his brain and control seemed unlikely. His daughter moved up her wedding date.

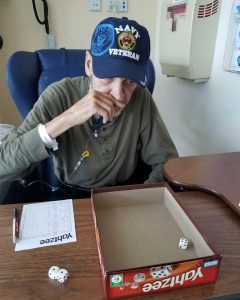

But Lenny Lewis wasn’t ready to give up.

Not only did he live to see his daughter get married, he danced with her at the wedding, and now, almost two years after he walked her down the aisle, indications are he’s cancer-free.

“I didn’t want to die,” Lewis says. “I just decided to mentally fight it. That’s what kept me going. That, and I just didn’t want to be without my family.”

Supporting this patient’s will to live was a small army of UConn Health providers in neurosurgery, oncology, radiation oncology, pulmonary medicine, and radiology.

‘Really Bad Headaches’

It was late summer 2017 when Lewis, a Navy veteran, found himself taking aspirin for headaches that were becoming more frequent and severe over a period of about two months. He’d been doing work outdoors and chalked it up to sun exposure. Then one day he blacked out and ended up at the UConn John Dempsey Hospital, where he learned he had a complex tangle of blood vessels called a brain arteriovenous malformation, or AVM.

The AVM itself was inoperable. But the multidisciplinary expertise available at UConn Health made radiosurgery a treatment option.

The headaches still persisted and repeat imaging a few months later revealed this tangle of blood vessels was concealing a brain tumor.

When Dr. Ketan Bulsara, chief of UConn Health’s Division of Neurosurgery, explained the situation, Lewis didn’t need much convincing.

“The first day he and I talked, he said, ‘I’ve got to operate on this to give you the best chance of recovery,’” Lewis says. “He thought I was going to maybe argue with him, but I said, ‘You gotta do what you gotta do.’”

When a tumor is embedded in an inoperable mass of blood vessels, removing it becomes a much higher-risk operation.

“Care had to be taken not to violate any of these blood vessels while resecting the tumor, because doing so would lead to severe neurological disabilities,” Bulsara says.

The operation went as planned and the tumor was resected successfully. But Lewis’s problems were far from over. There were other, smaller lesions on his brain.

“Lenny required stereotactic radiosurgery, or pinpointed high dose radiation therapy, to ablate several small spots in his brain,” says Dr. Charles Rutter from UConn Health’s Division of Radiation Oncology. “As with everything else, he was willing to do whatever he had to do to beat this.”

Beyond the Brain

With the first brain tumor removed and the radiation attacking the smaller brain lesions, the focus shifted. Imaging tests showed troubling spots on Lewis’s chest, liver, and abdomen.

And a large mass in his left lung.

“And then they started the chemo treatment,” Lewis says. “They said it traveled from my lungs up to my brain. That’s why I was getting the headaches I was getting. I mean, they were horrible.”

The prognosis was far from good. By March 2018, it appeared that neither the systemic tumors nor the brain tumors were responding. His condition continued to worsen and hope appeared dismal.

“There were two brain tumors on different sides of the brain that were contributing to his rapid decline,” Bulsara says. “They were causing a lot of pressure on his brain and limiting not only his survival, but also ability to get further treatments.”

Bulsara went back in, this time performing bilateral craniotomies to resect the lesions.

“As weakened as he had become, Lenny wanted to keep fighting,” Bulsara says. “He knew that our multidisciplinary UConn Health team and family was going to do all we could to continue to fight this with him. We needed more time to find a regimen that would treat his systemic tumors, but the brain tumors threatened to take away any time.”

It was around this time Patricia Desjardins, Lewis’s daughter, remembers deciding to move up her wedding date by nearly a year.

“Dad and I would spend sometimes five days a week at UConn,” Desjardins says.

At this point, Lewis also was under the expert care of Dr. Susan Tannenbaum, chief of UConn Health’s Division of Hematology/Oncology, and Dr. Omar Ibrahim, director of interventional pulmonology, for his other systemic tumors. Still, the plan to find a chemotherapy regimen to treat the lung metastasis wasn’t working.

“The side effects were horrible,” Lewis says.

He recalls being told he doesn’t have very long.

“That kind of blew my mind,” Lewis says. “And so I just said I’ll keep up with the treatments, pray, and do whatever you tell me.”

‘Our Last Option’

The next, and likely last, step was a relatively new therapy: pembrolizumab, a humanized antibody designed to catalyze the patient’s immune system to attack cancer cells. Considered not a chemotherapy but an immunotherapy, it’s not without its own risks, including the potential to also attack healthy organs and tissue.

Lewis recalls being told, “We don’t know if it’s going to work, but that’s our last option to fight the cancer.”

Through UConn Health’s Department of Surgery and Division of Neurosurgery, Bulsara and The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine (JAX) had established a tumor genomics pilot initiative. The tumor in Lewis’s brain was the first Bulsara sent to JAX for extensive sequencing.

“What was encouraging was, through this precision medicine initiative, this was a class of medications identified that would be beneficial for Lenny’s tumor,” Bulsara says.

It was early 2018 when Lewis started coming to the Carole and Ray Neag Comprehensive Cancer Center every three weeks to be infused with pembrolizumab, also known under the brand Keytruda.

“They put a port in my right chest area, near my shoulder, right next to my collarbone,” Lewis says. “They put a port because they were putting so many needles into my arms. That was really, really painful. I hated it.”

Turning a Corner

The regimen called for infusions every three weeks, and how long it continues depends on the patient’s response. Generally a patient will stay on pembrolizumab a maximum of two years – a life sentence to someone who’d been told he might have six months to live.

Every three weeks, Lewis would come in for the infusion.

“All the nurses and staff were very, very helpful and friendly,” Lewis says. “When I was going through that stage, every so often, you know, you just get in a crappy mood and you take it out on whoever’s around you. But they put up with it. That helped a lot, how they were friendly and they would help me in any way I wanted or needed.”

He was about five months into his infusions when his daughter would get married.

“The wedding went by so fast and I was really worried that Dad wouldn’t make it the whole day, or to our father daughter dance,” Desjardins says. “Boy was I wrong!”

Their song was “Hotel California” by the Eagles. She recalls tapping her fingers on his back in time with the drumbeats, and them singing the song to each other, as they did when she was growing up.

“He looked so happy he smiled and sang like the old times like cancer wasn’t even the reason he was 115 pounds, bald and scarred on his head from multiple surgeries, and for that moment life seemed normal again,” Desjardins says. “I’m glad we moved it up and honestly it was a perfect day.”

But it was still unclear how many days would be left. Christmas with Dad was far from a certainty.

But another five months went by, then then five more, and as he continued the immunotherapy, something remarkable was happening.

“His systemic tumors started disappearing and nothing new appeared in the brain,” Bulsara says.

‘Simply Outstanding Results’

The combined expertise of UConn Health and JAX had led to a therapy that would change the trajectory of Lewis’s treatment.

“Lenny started off with a drug that was expected to work very well,” Rutter says. “However, when that failed he moved on to immunotherapy, which revs up his immune response to his cancer. That has led to simply outstanding results in his case.”

Earlier this year, as the state and country were on the verge of COVID-19 lockdown, Lewis reached the end of his two-year window with pembrolizumab. A late-spring positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed no active disease.

“I got lucky as hell the Keytruda killed the cancer when the medication period ran out and the pandemic started,” Lewis says. “So I guess God was working on my side.”

“When COVID-19 surfaced in the United States they stopped dad’s treatment and I was worried the cancer was going to return full force and we would lose him during a time that family cannot enter the hospitals to be with loved ones,” Desjardins says. “I have to tell you the only good thing that came out of quarantine was the diagnosis of my father being told he was in remission!”

Lewis, who lives in Killingworth, turns 59 this fall.

“We just can’t say enough about Dr. Bulsara and Dr. Rutter, and all the wonderful doctors and nurses at UConn,” says Faith Meyers, Lewis’s sister. “Seeing what they did for my brother, it’s clear, UConn is the place to go for health care. All my doctors are at UConn now, and I wish I’d done that years ago.”

Bulsara says the span of specialties involved in this success story demonstrates UConn Health’s continued commitment to being a world-class destination center for care.

“Multidisciplinary care of patients is optimizing outcomes,” Bulsara says. “And the addition of medical neuro-oncologist Kevin Becker to the Carole and Ray Neag Comprehensive Cancer Center last fall is yet another example of a programmatic treatment dimension added for patients with brain and spine tumors.”