Authors Javon Adote, Haylie Alter, Margot Eversdyke, Calista Giroux, Madison González, Phillip K. Graham, Alyssa Harvey, Sarah Hubelbank, Iris Jordan, Christine Jorquera, Rosemary O’Mahony, Mercedez Patrick, Angelica Sistrunk, and Eddie Vitcavage are students at the University of Connecticut, where they were enrolled in ENGL 2203-001 and -003 in the fall of 2019.

[Editor’s note: Earlier this summer, as the US saw the beginning of the largest protest movement in its history, English PhD candidate Anna Ziering organized a collaboration with former students on an activist writing project in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. The process built on coursework from Ziering’s FA 19 course “American Literature Since 1880” (ENGL 2203), which closed with Angie Thomas’s YA novel “The Hate U Give.” Using Zoom and GoogleDocs, a team of twelve students worked together, building on their experience in two different sections of the class and, says Ziering, “organically sharing their diverse perspectives, experiences, and histories of activism.” They produced the following piece, demonstrating an application of their classroom skills to the wider world.]

Breonna Taylor. George Floyd. Tony McDade. Riah Milton. Dominique Fells. Rayshard Brooks. Oluwatoyin Salau. Victoria Sims. Racism has outlived them all.

In Angie Thomas’s YA novel The Hate U Give (2017), sixteen-year-old Khalil Harris explains Tupac Shakur’s THUG LIFE tattoo as a comment on systemic racism: “The Hate U Give Little Infants F—s Everybody.” Minutes later, Khalil is murdered by a police officer in front of his friend, Starr Carter. In the aftermath, Starr’s father elaborates: “the hate they’re giving us, baby, [is] a system designed against us. That’s Thug Life.” And Starr realizes, “it won’t change if we don’t say something.” This reading from our American Literature class last fall came to mind when we saw Donald Trump threaten military action against Black Lives Matter protestors, calling them “THUGS”—a moment that illuminated just how clearly our government picks and chooses between its people. To this president, non-violent Black Lives Matter protesters working for an anti-racist United States are “thugs.” Gun-toting white people protesting national health guidelines are “good people” who “want their lives back again, safely!”

None of this is new. Black people have never been safe here, as the growing list of lost Black lives makes painfully clear. Black people have been subject to anti-Black violence in this country since before it was a country—to kidnapping, enslavement, Jim Crow, neoliberalism, prison- and military-industrial complexes. This is not the history we are usually taught in school. But this is the history we acknowledge—the history of a community currently rising up in self-defense after hundreds of years of violent oppression. At first, some of us felt ashamed of this history. Now, we are angry. This is the history we refuse to be silent about; silence is a privilege that we cannot afford. Nuestro fuerza viene en la unidad.

A Newsweek piece earlier this summer asked where college activists were, implying that a lack of campus action means we have been silent. Of course, we’re not on campus—UConn closed for the pandemic in March. But we’re right here. We are Black, Latinx, biracial, white-passing, and white, ages eighteen to forty-one, from Simsbury, South Windsor, Bridgeport, Southington, Fairfield, Trumbull, and out of state. We are UConn students in neurobiology, physiology, urban and community studies, English, psychology, Spanish, human rights, agriculture, health, theater, engineering, education, and linguistics. Some of us have studied racism since childhood, without ever having a choice; those of us who think about our skin only when it freckles in the sun came to the issue later. It has been hard to discover that a system we were taught to admire is fundamentally unjust, hard to spend years unlearning the racism taught to us in our childhoods. But it has been harder for those of us who live, every day, with the constant reality of racist violence.

So we are taking action. When our campus was open, we organized there. Now, we are leading protests, attending marches, signing petitions, on phone and Zoom calls, on texts and DMs, having conversations at the dinner table, reading books and watching documentaries, making posters and donations, and staying home to protect ourselves from the double threat of anti-Black racism and COVID-19. We study our privilege, our histories, our mistakes, and our progress. We talk to our families and friends, explaining intersectionality and social entanglements. We remind our communities that immigration policy and gender justice are inextricable from anti-racism and access to education.

In The Hate U Give, Starr’s father tells her, “The system’s still giving hate, and everybody’s still getting f—ed…And we won’t stop getting f—ed till it changes. That’s the key. It’s gotta change.” But how do we change it? What will all this lead to? How do we find justice? We’re not sure. We’re still learning. But for now, we march. We speak. We demonstrate and protest. We challenge and educate ourselves. We stop supporting businesses that issue platitudes without action, business without people of color in leadership or with unjust labor conditions for their workers. We rally, register, and vote in every election from the local to the federal level. We make art and we make noise.

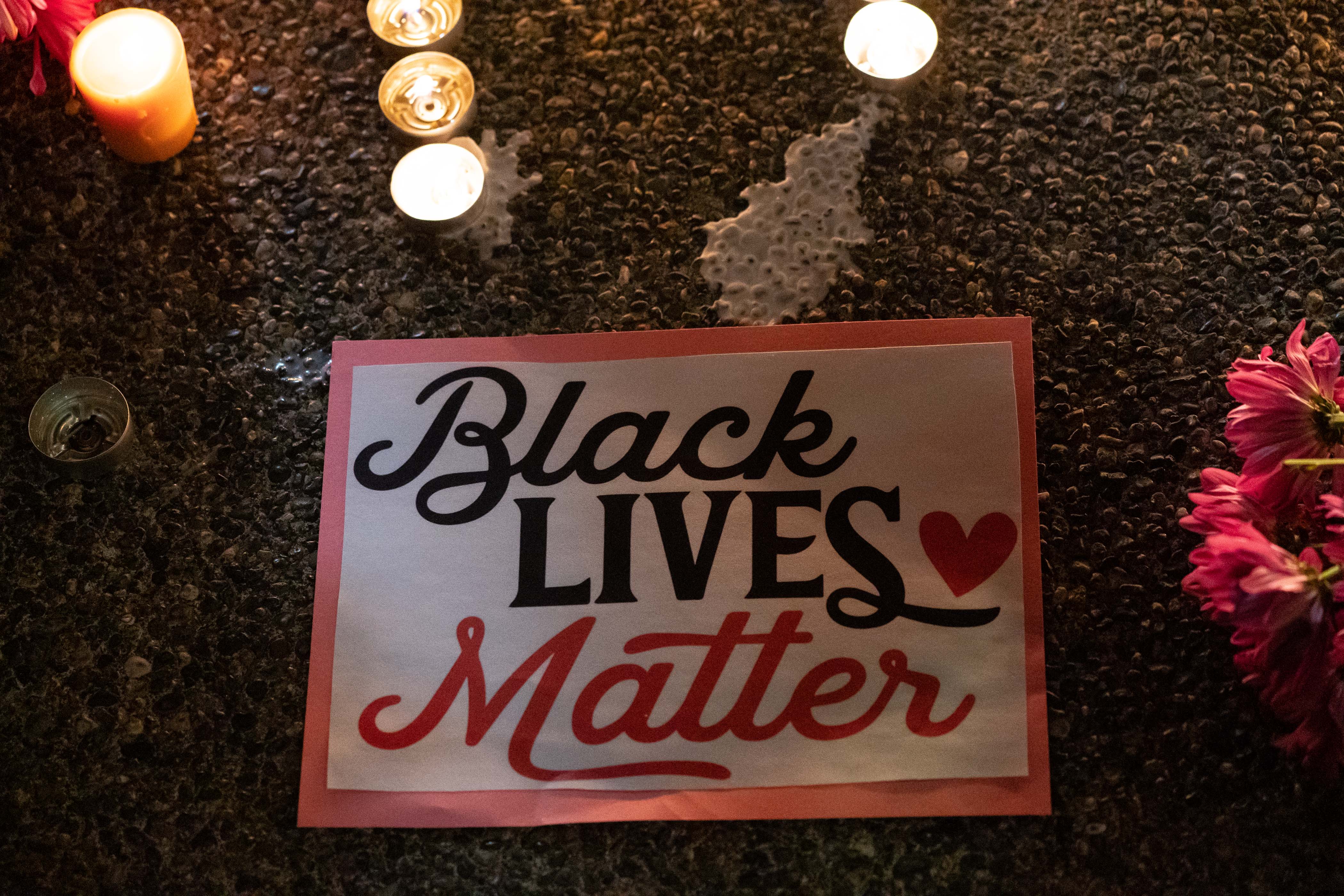

At the 2019 March of Solidarity, organized by UConn Collaborative Organizing, students hesitant to add their voices to the cry of “Black Lives Matter” were answered by a peer: “Say it like it’s my life, because it is.” It is time to stop prioritizing the comfort of those who benefit from systemic oppression over the lives of people being oppressed—time to stop prioritizing white comfort over Black lives. Change is coming; we are bringing it. And so we say: Black lives matter. Black women matter. Black queer people matter. Black trans people matter. Poor Black people matter. Black immigrants matter. Black children matter. Black incarcerated people matter.

Black Lives Matter.