A collaborative, international effort to study parathyroid tumors is needed to uncover potential treatments, reports a multidisciplinary panel led by UConn Health and the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Advanced parathyroid cancer is deadly but rare, and finding enough patients will be crucial for development of badly needed new therapies for this disease.

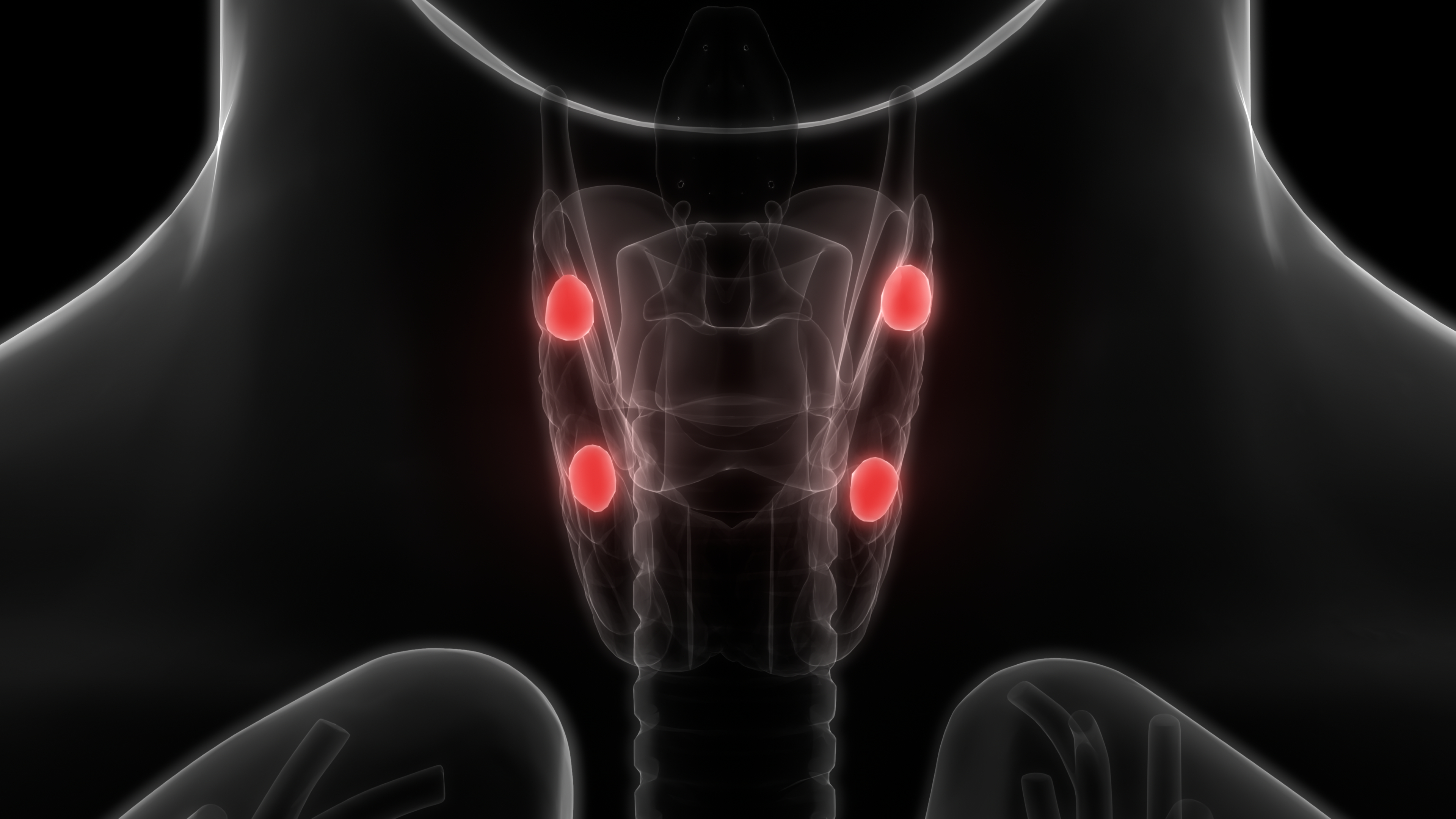

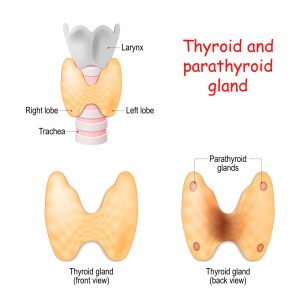

The parathyroid may be the most important set of glands you never knew you had. First discovered in 1852 during the dissection of a deceased Indian rhinoceros cadaver, the parathyroid glands are very small. In humans they’ve been described as four lentil-sized bits of tissue on either side of the thyroid; even in a rhinoceros, each “lentil” is barely a centimeter in diameter. But though it’s small, it’s crucial to proper calcium flow through the body. If the parathyroid malfunctions it can destroy both your bones and your kidneys.

The parathyroid’s major job is to regulate the amount of calcium in the blood. Calcium is famously important for the hardness of our bones and teeth. However, it’s just as important for cells, which use it to generate electrical fields that open and close membranes and carry messages along our nerves. Because of its vital roles, our body is very good at keeping calcium available at stable levels in our blood. The bones act as a calcium reserve, and if the level drops too low, the parathyroid glands release parathyroid hormone (PTH) to tell the bones to release a little. PTH also tells the kidneys to retain calcium instead of peeing it out, and the hormone acts indirectly on our guts to tell them to scavenge more calcium from our food.

The most common type of parathyroid disease is actually caused by chronic kidney disease. The kidneys lose function and don’t retain enough calcium, so levels in the blood continually drop. The parathyroid has to work overtime, releasing large amounts of PTH and growing bigger, sometimes turning into a benign tumor, in an effort to keep the heart and nervous system functioning. Meanwhile, the bones lose calcium and eventually develop osteoporosis.

Fortunately, if the kidney disease is treated and, if necessary, any parathyroid tumors are removed, the bones regain calcium and everything comes back into balance. The same positive outcome happens if someone develops a benign parathyroid tumor without kidney disease, also a common scenario. Surgical removal is typically successful and patients make a full recovery.

However, there’s a third kind of parathyroid disease, parathyroid cancer. It’s very rare, but hard to cure. Even when the primary tumor is removed, it can recur in the neck or spread to the lungs or elsewhere, in 50% of patients. Neither traditional chemotherapy nor radiation therapy has been effective in such advanced disease, so finding new therapies is essential. A team led by Dr. Andrew Arnold, the chief of endocrinology and metabolism at UConn Health and Professor of Medicine and Genetics and Genome Sciences at the UConn School of Medicine, has made important headway by discovering several key genetic derangements responsible for the growth of these cancers.

“The genetic insights we’re now looking for in the lab is how…these gene mutations are driving the tumor growth,” Arnold says. “We could hopefully find very targeted therapies to shut the tumor down.”

Another key goal of the researchers is to develop parathyroid cell lines that can be grown in the lab.

“In culture, they don’t grow well. Right now, they’ll stay alive, but they stop acting like parathyroid cells. They stop making PTH,” says Dr. Jessica Costa ’09 (DMD, PhD), a cancer researcher at UConn Health and assistant research professor at the UConn School of Medicine . “We need to get better at knowing what makes a parathyroid cell a parathyroid cell,” and creating that environment in the lab, Costa says.

Costa, Arnold, and the other national leaders who authored the report, which was published in August in Endocrine-Related Cancer, emphasize the need for a collaborative, international effort to identify parathyroid cancer patients and share tumor tissue and data, a need for better imaging of parathyroid tumors, more genetic analysis of the tumors, and cell lines so that drugs to treat parathyroid cancer can be tested in the lab.