Melatonin is used as a dietary supplement to promote sleep and get over jet lag, but nobody really understands how it works in the brain. Now, researchers at UConn Health show that melatonin helps worms sleep, too, and they suspect they’ve identified what it does in us.

Our bodies produce melatonin in darkness. It’s technically a hormone, but you can readily buy melatonin as a supplement in pharmacies, nutrition stores, and other retail shops. It’s widely used by adults and often in children as well.

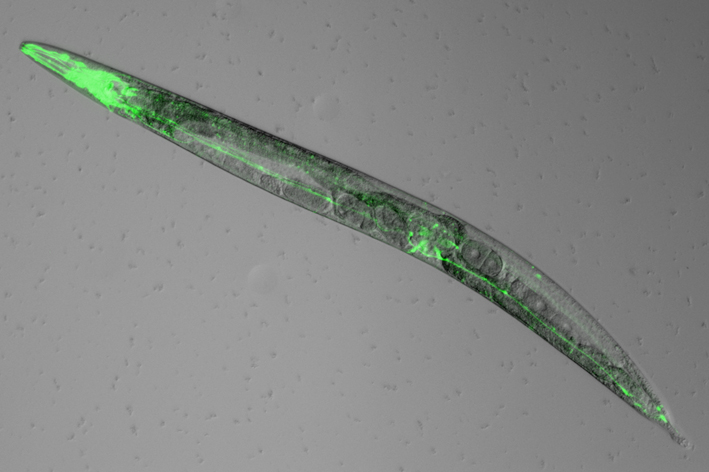

Melatonin binds to melatonin receptors in the brain to produce its sleep-promoting effects. Think of a receptor as a keyhole, and melatonin as the key. The two keyholes are called MT1 and MT2 in human brain cells. But scientists didn’t really know what happens when the keyhole is unlocked. Now UConn Health School of Medicine neuroscientists Zhao-Wen Wang and Bojun Chen and their colleagues have identified that process through their work with Caenorhabditis elegans worms, as reported in PNAS on Sept. 21. When melatonin fits into a receptor in the worm’s brain, it opens a potassium channel known as the BK channel.

A major function of the BK channel in neurons is to limit the release of neurotransmitters, which are chemical substances used by neurons to talk to each other. In their search for factors related to the BK channel, the Wang and Chen labs found that a melatonin receptor is needed for the BK channel to limit neurotransmitter release. They subsequently found that receptor. When the BK channel is activated, less neurotransmitter is released, meaning the neurons quiet down and don’t talk to each other as much. In worms, as in humans, that appears to be the state we call sleep. Worms that lack either melatonin secretion, the melatonin receptor, or the BK channel spend less time in sleep.

But wait—worms sleep?

Indeed they do, says Chen. There’s actually been quite a lot of research on worm sleep, and researchers found that sleep is similar between worms and mammals like humans and mice.

Wang and Chen next plan to see if the melatonin-MT1-BK relationship holds in mice. The BK channel is involved in all kinds of bodily happenings, from epilepsy to high blood pressure. By learning more about the relationships between the BK channel, sleep, and behavioral changes, the researchers hope both to understand melatonin better and also help people who suffer from other diseases related to the BK channel.