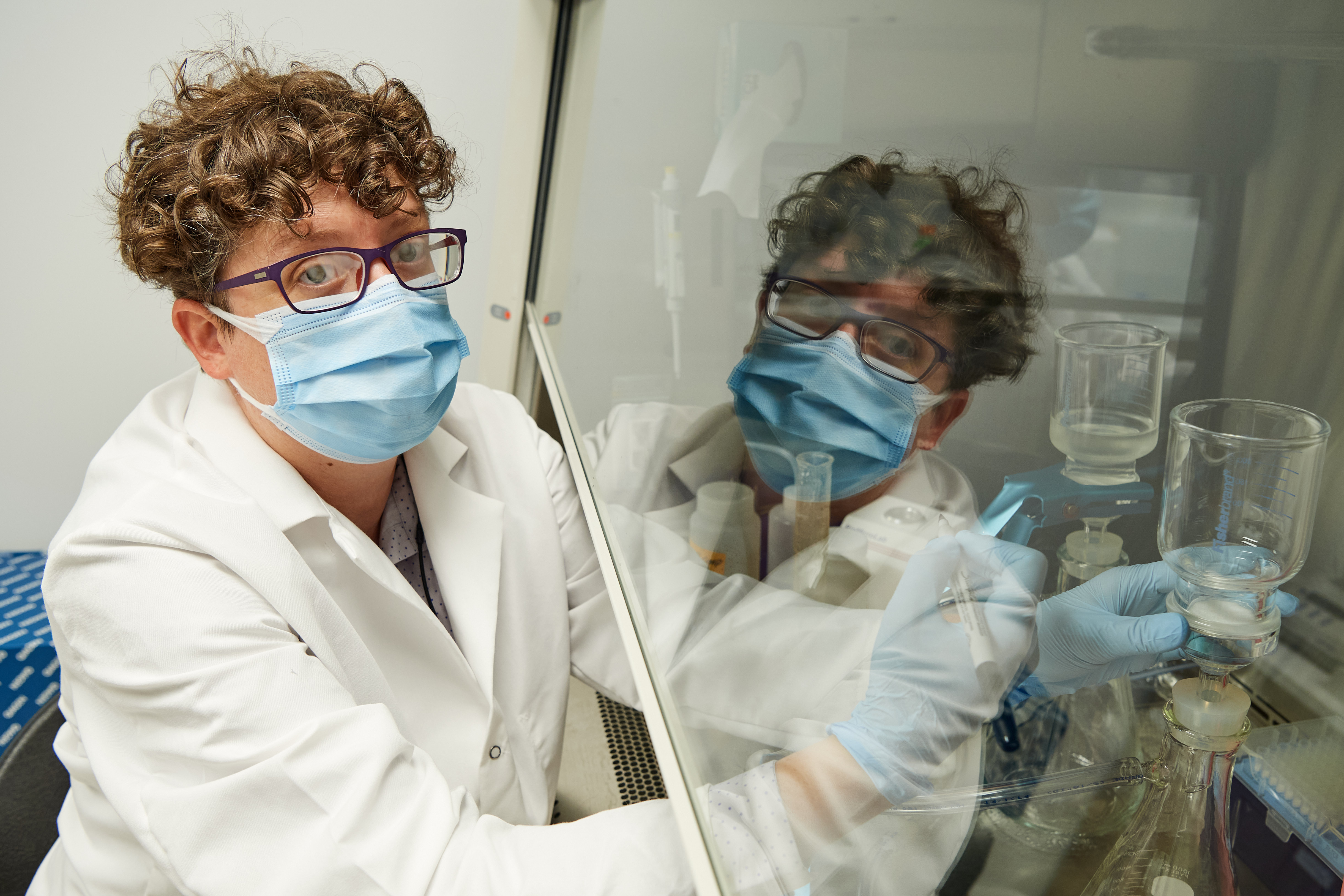

Kendra Maas tested 680 samples of wastewater from the Storrs campus for the COVID-19 virus during the fall 2020 semester.

And she still doesn’t think wastewater is all that gross.

Saliva samples, though, are another story.

“Pooled saliva is not as gross, because we’re doing gargle samples, so it’s like a little bit of water that you gargle for 10 seconds and then spit back into the tube,” she says. “But when you tell someone to spit in a tube? It’s just so gross.”

Maas, who works as the facility scientist for UConn’s Microbial Analysis, Resources, and Services laboratory, also known as MARS, is getting ready for more spit, and more wastewater, when campus reopens for the spring semester. Her lab will again be processing pooled saliva samples as part of the University’s multi-pronged coronavirus testing and surveillance program. She’ll also continue testing samples of campus wastewater from the 15 pump locations that were established and installed during the fall as well as from new locations that they’re setting up over the winter break.

“We’ll be putting pumps on some additional buildings – including the facilities and warehouse buildings – just to capture that area, because that’s a huge proportion of the population on campus right now,” Maas says. “I’m also trying to figure out where to put a pump on the science complex. That one is difficult because of construction.”

Adding difficulty for Maas and her lab team – which included one post-doctoral student, three graduate students, and two undergrads during the fall semester – is Connecticut’s winter weather, which has already caused some of the wastewater sampling pumps to freeze.

Maas, though, is currently testing a new sampling method using a common, inexpensive, and highly absorbent product that would allow samples to be taken in areas where a pump cannot be installed, as well as eliminating the problems caused by frozen pumps.

“We put out this absorbent product, otherwise known as a tampon,” Maas says, “and it sits in the sewer, in the wastewater, and you let it absorb for 24 hours and then quantify the virus from that.”

Maas, who is in regular contact with wastewater testing colleagues from around the globe, said the “tampon method” has been deployed with success by a researcher in Colombia, who is unable to purchase pumps, as well as a scientist in Arizona who wanted to develop a more cost-effective method that could be deployed across the Navajo Nation. Over the winter break, she plans to test the method’s effectiveness on her own by comparing tampon samples with those collected from the pumps, with the hopes of deploying both sampling methods during the spring semester.

“There’s some dorms that we can’t get pumps on,” she says, “because there’s nowhere to put a pump. Then there’s other dorms where we can get a pump, but it is 10 buildings. So, we could have a pump going there, and then also sample a few of the buildings with the tampon method.”

Maas initiated the wastewater testing program over the summer and began deploying it around the start of the semester. Shortly after an individual contracts the coronavirus, they begin to shed large amounts of the virus through their feces, typically before they show any symptom of illness. Researchers believe that wastewater testing can begin to show increased viral abundance – evidence that an outbreak is about to occur – up to seven days before individuals become symptomatic.

Maas had hoped that wastewater testing on campus would give an early warning of when outbreaks might happen, and where they were starting to occur on campus. Instead, though, the wastewater testing became more of a backstop – confirming the validity of the University’s individual and pooled testing programs and contact tracing efforts.

“Student Health and Wellness is so good at their contact tracing, that most of the time I would tell them that I was seeing a spike, and they had already found it through contact tracing,” Maas says. “And that’s not a bad thing at all. In September, I would have been worried about the low levels I was seeing, except Student Health and Wellness was also seeing no positives. And at the same time, they felt better that all of their negative tests were okay, because they had the wastewater to prove that it was correct.”

Cities and towns have a much more difficult time conducting contact tracing, Maas says, which is where the seven-day lead of wastewater testing may prove most valuable. She’s opened up her lab – from the outset, she purposely built in capacity to test a significant number of samples at a time – to municipalities within the state looking to use their wastewater systems to track infection. The towns of Manchester, Windham, and Glastonbury are all currently supplying Maas with samples to test, and she has plans to work with the U.S. Coast Guard Academy and the University of Hartford on wastewater testing in the spring as well.

“There’s a few more towns that I have heard rumors about, that they’re going to be talking to me,” she says, “and we still have plenty of capacity.”

While she has also been building the methodology to begin testing wastewater for influenza as well as COVID-19 – flu viruses are similarly shed through fecal material – those plans have been put on hold for now, because there hasn’t been any influenza to be found.

“The thought was that it would be good to tease out who has flu-like symptoms because of influenza and who has flu-like symptoms from COVID,” she says. “The thing is, though, there’s no influenza right now. Anywhere. Because masking works. It’s incredible, and it’s a great side effect, because when people were saying, ‘COVID is just a flu’ – well, no, it’s worse than the flu. It’s worse than the worst flu year. But also, the flu is not good. We should be trying to prevent the flu.”

Maas says that a new informational website has been created that includes information about various wastewater testing methods. The plan, she says, is to eventually use the site as an automatic data repository, making public results and data from the wastewater testing program for broader use by researchers and members of the public.

The MARS laboratory will also be ramping up pooled saliva sample processing, in coordination with Student Health and Wellness, for the spring semester. Residential students will receive instructions and sampling kits when they arrive on campus, while off-campus students will receive information from SHaW with instructions for weekly pooled sampling. The testing option is voluntary, with the hope that students will sign up and participate in order to help in the COVID-19 surveillance and containment effort in Storrs.

Maas says UConn students took the threat of the coronavirus seriously, and were conscientious about engaging in behaviors to reduce the virus’s spread on campus. But she does have one request for students returning in the spring.

“Please stop flushing paper towels,” she pleads, along with so-called “flushable wipes,” which are not actually meant to be flushed.

“They wrap around the inlet of the pump tubing and really clog it. So, please just stop flushing paper towels.”