David K. Ware didn’t know that the modest Cape Cod-style house where he grew up in Manchester held a secret past until he was in his late sixties and studying for his Master of Laws (LLM) degree at the UConn School of Law.

“I visit with my father, who still lives in Manchester, a couple times a week,” says Ware, who earned his law degree from UConn in 1976 and completed his LLM in 2020. “I was visiting with him while I was studying for my LLM, and typically I would talk to him about the topics I was studying and the ideas that we were discussing in these classes.”

One of those classes was about the interconnection of race and property rights in United States’ history and, after one of their talks, Ware’s father produced documents related to their family home that the son had never seen before.

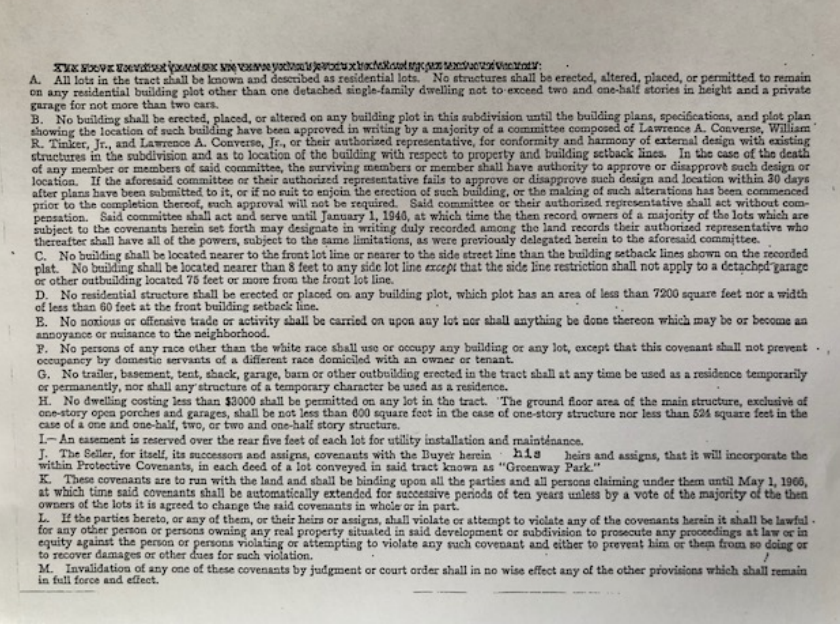

“When I went over to see him, he showed me a copy of a deed in the chain of title for his house in Manchester, which is the only house he has ever owned and the house I grew up in,” Ware says. “The old deed that he showed me had one of these restrictive race-based covenants.”

Restrictive covenants are a legal tool used to impose limits on what can and cannot be done with a piece of property. Most are innocuous enough – limiting the size or number of structures on a parcel of land, set-back requirements, prohibiting certain uses of the property, or things of that nature.

Other restrictive covenants are the opposite of innocuous: They are overtly racist statements prohibiting people from certain racial or ethnic groups from owning or residing on the property. And it was one of these racially restrictive covenants that Ware found himself reading in the deed to his childhood home.

“It was the first time I had ever known about it, and it had, I think, only recently become known to my father,” Ware says. “He’s very interested in history and ancestry– he loves things like looking through old records. So, it doesn’t surprise me that he had copies of all of the old deeds concerning his property.”

Ware continues, “He showed this to me, and that’s what really sparked my interest. I said to myself, ‘I wonder just how prevalent these things are, and what properties they affect, and what their history is, and what’s up with these things?’”

With the support of his professors, Ware dove deeply into the history of the development of his father’s house, as well as other developments in Manchester. He found three subdivisions – the Greenway development, where his father lives; the Lakewood Circle development; and the Bowers Farm development – that were founded in the 1940s, which all contained racially restrictive language in their property records.

Ware also looked closely at federal and Connecticut law. While the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1948 that enforcement of racially restrictive covenants was a violation of the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, there was no mechanism in Connecticut law either to remove the covenants from land records or to declare them invalid.

“I learned through my research that there were, at that time, only about six states in the country that had enacted statutes that address these things and that provide a way for people who have these kinds of covenants in their in their chain of title to do something about them,” Ware says. “Connecticut did not have such a statute, and I asked around a little bit. No one had ever heard of anyone in Connecticut ever trying to get one done.”

Ware detailed his findings and research in an extensive report entitled, “The Black and White of Greenway: Racially Restrictive Covenants in Manchester, Connecticut.” But his work didn’t end there.

“I decided that Connecticut should have a statute,” he says, “and ours should adopt the best features of the statutes in other states, while avoiding or improving upon other features that I considered less desirable. I wanted our statute to provide a simple, unburdensome, and inexpensive way to repudiate these old tools and expressions of racial segregation.”

Ware is not a creature of politics. He had never interacted with his state legislators, never written a state statute, never testified before a legislative committee, and never watched how a bill becomes a law in the Connecticut General Assembly. But he wanted to create a process where landowners, upon finding that their property contained a racially restrictive covenant, could take action to declare the restriction void.

“I gave myself a task of figuring out how we could have a statute in Connecticut that would help identify these things and repudiate them, or refute them, or call them out for what they are – blatant statements of racism,” he says. “Albeit old, and albeit not technically legally enforceable, nevertheless, they still sit there in the land records.”

He started by attempting to craft a statute, enlisting help from advisors at the Law School, before writing letters to state legislators from the town of West Hartford, where he lives now, and from Manchester. All of those he contacted were supportive, he says, and he found particular champions in Manchester state Rep. Jason Doucette ’03 JD and state Sen. Gary Winfield of New Haven, co-chair of the legislature’s powerful Judiciary Committee, who raised a bill, refined it, and passed it unanimously out of the committee in April 2021.

In the waning days of the 2021 legislative session, both houses of the General Assembly passed the bill – House Bill 6665, An Act Concerning the Removal of Restrictions on Ownership or Occupancy of Real Property Based on Race and Elimination of the Race Designation on Marriage Licenses – in unanimous votes, and it was signed into law by Governor Ned Lamont on July 12, 2021.

“I didn’t really expect to have something happen so quickly,” Ware says. “I mean, I always had confidence in it, one way or another, even if it meant my having to stick with it through multiple sessions. I had in the back of my mind that, well, if it doesn’t make it through this year, we’ll make sure we bring it up next year, and I’ll just keep after it. So, it was pleasing, and surprising that it got the kind of attention it got so quickly, and that there was such a unanimous favorable response to it.”

The legislation took effect retroactively on July 1, and it formally declares any racially restrictive covenant attached to land records on property in the state to be void. It further allows a property owner who discovers that their land records contain a racially restrictive covenant to file a formal affidavit or other document, to be recorded into the land records by the town clerk, to identify the offensive covenant and show that it is void.

“I’m a 70-year-old white man,” Ware says. “I haven’t walked in the shoes of people of color, women, or other groups who have been marginalized. I have been the beneficiary of the kinds of privileges that white men have enjoyed forever. If I were to put myself in the shoes of, as the covenant says, a person other than someone of the ‘white race,’ how would I feel if I came upon that in the chain of title for my home that I’m living in? Yes, it is legally unenforceable, but it’s sure not going to make me feel good – it’s a stark and blatant and upsetting reminder of where the country has been.”

Ware hopes that his now 95-year-old father will be among the first to file his affidavit with Manchester’s town clerk, and he wants to spread awareness of the new law so that others will feel empowered to denounce racist covenants in their own property records.

“Officially recorded expressions of racism, like those contained in these covenants, can project an air of legitimacy – they can entrench and encourage the attitudes that animated them,” Ware says. “Fortunately, the Supreme Court has held that it is unconstitutional to enforce these covenants. So, if it is illegal to enforce them, we should not let them reinforce the racist attitudes they represent by allowing them to remain unrefuted in our official and formal records.”

He continues, “The latest and most official statement concerning covenants like this should not be their original formal creation; rather, it should be their present-day repudiation – the unambiguous declaration that such a covenant is unacceptable and void. I want all of us, especially the people who are called out, who are ‘othered’ in those covenants, to have the ability to say just how they feel about those things, and to literally set the record straight.”