The sight of felled trees and logging activity can be jarring for nature lovers, but from those sites can sprout young forest growth that’s especially attractive to a familiar inhabitant of wooded areas throughout the Northeast – bats.

New findings from researchers at the UConn College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources, published in Forest Ecology and Management, finds that a number of bat species native to the Northeast are highly active in newly created forest spaces, foraging for food at higher rates than is typical of mature forests.

Little is known about how different bat species use forests of varying ages, but Natural Resources and the Environment researchers – including Dan Wright ‘20 (CAHNR) MS, Associate Professor Tracy Rittenhouse, and Assistant Professor in Residence Chad Rittenhouse – sought to learn more. What they found sheds new light on how forests can be managed to support bat populations, most of which are threatened or in decline, says Chad Rittenhouse.

“The reason people haven’t worked on this (summer habitat) in bats is due to white nose syndrome and the spread of the disease causing the rapid decline of populations,” he says. “The conservation efforts around bats, rightfully so, were really focused in on the hibernaculum caves where the mortality was happening, and where the disease contact between individuals is happening. However, there is this whole foraging and young-rearing period that hasn’t been looked at, and we don’t know the details of what happens.”

Chad Rittenhouse explains that this research focusing on bats sprang from similar research he did in graduate school with birds.

“There was an emphasis on what’s called post-fledging ecology of birds, basically finding out what birds do after they leave the nest but before they migrate,” he says. “When the young leave the nest, they are going for canopy gaps and small openings within the forest. We didn’t really know that previously and through radio telemetry studies and observational studies found that that they were doing that because there is more sunlight, which means more vegetative growth, which means more insects feeding on the vegetation growth, which means young birds can grow more quickly through increased insect consumption. There’s also a lot of structure, vertical and horizontal, that was providing cover from predators.”

The researchers knew the DEEP Wildlife Division has a bat monitoring program that mainly tracks bats along roadways, where they often forage and commute, says Chad Rittenhouse. Reminded of the fledging bird research, they thought about applying methods that have been used on birds to learn about how bats use forested habitats, and in areas where forest management treatments have been applied.

“Why not look at bats off roads? Why not look at bats in these cut areas? We thought we should look at bats and clear cuts and regenerating forests and just see what’s going on. A quick peek at the scientific literature revealed literally only a handful of studies that have looked at this issue.”

Tracy Rittenhouse explains the experimental setup, which took place in northwestern Connecticut and southwestern Massachusetts: “We picked sites that were embedded, meaning the sites had mature forest, with a smaller — depending on how you define smaller – harvested stands embedded within mature forests.”

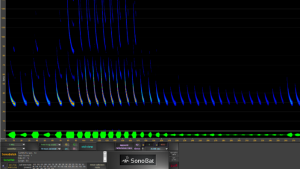

The forest locations varied in age from one to 12 years of regrowth since trees were cut, where researchers then recorded bat foraging calls at night. Through this passive acoustic sampling, they were able to track bat foraging behaviors and identify which species were present.

“We paired every one of our sites that was a cut site with a nearby control site, typically within 100 meters or so which was not cut. What we have is a nice comparison of how bats are using the mature forest and the cut forest,” says Chad Rittenhouse.

Tracy Rittenhouse says the results showed a strong pattern where bat foraging activity was the highest in younger forests, and that it steadily declines as the forests age. By day, bats can roost in a variety of structures, resting up before their nocturnal foraging acrobatics, from the eaves of houses or beneath curls of bark on shagbark hickory trees.

“We tend to think that old growth forests must be good for bats, because we know they contain roosting sites, but within 24 hours [of a tree cut], they’re roosting and foraging.”

Wright adds, “After a cut happens in the forest, bats are really active, using it as both commuting and foraging habitat. As the cuts continue to age, the vegetation height increases, and the foraging space, up in the air, where bats typically forage is not as suitable anymore.”

With knowledge of the bat foraging preferences, Tracy Rittenhouse says future studies will include taking a closer look at roosting preferences, but what is clear is that homogenous forest age does not meet the range of needs for everyone.

Though cut trees and logging can be a jarring sight, studies like this one illustrate the importance of management and the impacts on animal populations, says Chad Rittenhouse.

“An important point is that young forest is still forest. I think a lot of people don’t think of it that way, but to get to replacement of old trees, we need young trees too. We’ve been beating this drum about young forests being really important because there are lots of species that are associated with and dependent on young forests.”

Wright says, “Forest management in terms of harvesting trees can be a huge asset to wildlife, wildlife conservation, in general. I think our work is pretty great in helping to manage forests and manage sustainability with productivity.”