While many can say where they were and what they were doing when America came under attack Sept. 11, 2001, a relative few can say there were physically at the World Trade Center site in the hours that followed.

Two UConn Health physicians were among those who found themselves amid the rubble that day in Lower Manhattan, responding to offer assistance at the site that would become known as Ground Zero.

“At the time I felt like I was there doing something as best I could, at least being available. And now I look back and I’m like, ultimately we weren’t able to do that much,” recalls Dr. Robert Fuller, chair of the UConn John Dempsey Hospital Emergency Department.

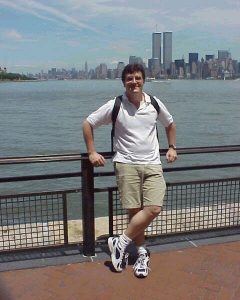

At the time Fuller was 37, the hospital’s EMS medical director. In that role he regularly trained with first responders as part of the UConn Health Fire Department’s special operations unit, skilled in response to potential mass casualty events or other situations requiring specialized training and equipment. He reported to work that morning and found people gathered around the television in the ED waiting room.

“Everybody was shocked about what was going on,” Fuller says. “And I wasn’t there for a minute or three till someone from the fire department called up and said, ‘Is Fuller there? We’re putting together a team to go.’”

That same morning, a 31-year-old medical student named Dirk Stanley was attending the morning report at Brooklyn Hospital, where he had just started his pediatric rotation. He was in his third year at the St. George’s University School of Medicine. He recalls someone interrupting to announce some kind of explosion at the World Trade Center.

“I ended up in the nursery looking out the window and there was one tower standing there with smoke pouring out of it,” Stanley says.

Today UConn Health’s chief medical information officer, Stanley recalls thinking the angle he was watching from obscured his view of the second tower. He also remembers trying, unsuccessfully, to call one of his best friends, who worked at the World Trade Center.

“All of the sudden that tower that’s standing there, it starts crumbling down,” Stanley says. “Where’s the other tower? I didn’t even know what was happening. And now, all of us are in sort of a sense of panic.”

As trainees with undefined responsibilities, Stanley and his peers rushed to the ED, where patients already had started arriving and where providers were too busy to precept students.

“So I walked outside and I’m looking at all these people flooding Flatbush Avenue,” he says. “I don’t know where to go, I don’t know what to do, and I think my best friend just died.”

‘New York City Is Closed’

Back in Farmington, hospital leadership was meeting about what could be done to prepare for what clearly had become a mass casualty catastrophe. Fuller told the group he’d like to mobilize the special operations unit to go to New York City and assist with the response.

“I told them briefly who we were,” Fuller says. “I remember [Executive Vice President for Health Affairs] Peter Deckers saying something like, ‘Rob Fuller can have whatever he wants. Go.’”

Fuller and a team of UConn Health firefighter paramedics and Farmington volunteer firefighters started to assemble their gear and a convoy to drive down.

“You know it’s not right when you’re driving there and there are no cars on the road — Zero cars on the road, anywhere, on the highways,” Fuller says. “Before the New York border it was clear. The changeable electronic announcement signs on the side of the road, they said, ‘New York City closed.’ Instead of saying ‘travel advisory,’ it said, ‘New York City closed.’”

‘Everything Smelled Like Burning Oil’

In Brooklyn, Stanley found himself walking toward the Manhattan Bridge with two physician assistants.

Though not fully trained as a physician yet, Stanley was a certified emergency medical technician. His path to medical school went through Valhalla, New York, where he served for nearly five years with the volunteer ambulance corps and was the Thursday night crew chief. The experience provided many interactions with police and firefighters, as well as training for disaster responses.

Mostly by foot, and with some help from a police cruiser where traffic allowed, they made their way to the intersection of Broadway and Fulton Street.

“It’s all dust. It’s loaded with emergency vehicles, burning cars, and every once in a while you see some poor business person with a suit covered in dust and their briefcase running off in the corner. There’s nothing but dust and girders and burned cars on their sides,” Stanley says. “We’re walking forward and now it’s getting really dark and we can’t see much of anything, but we gotta keep going. When I replay it in my head, it’s midnight, which is so bizarre because in reality this is like 11 o’clock on the most beautiful, bright, sunny day. That’s how much badness there was.

“Everything smelled like burning oil, and I remember closing my teeth and, you know when you get sand in your mouth and your teeth are crunching?”

‘The Wrong Ratio’

Approaching Manhattan, the UConn Health convoy reached a New York City Fire Department checkpoint.

“We could see the smoke in the sky real easy. It seemed close. It seemed big,” Fuller says. “It was daytime, bright, sunny, beautiful day, late afternoon. And we drove and then suddenly it was lights out. It was pitch black. And we’re still driving. And we drove until we parked next to a jet engine, we drove right up to, the tires almost into the rubble, we’re right there. We were able to drive right up into the dust. It was pretty impressive and we didn’t expect to get that close.”

There they integrated themselves with the FDNY response.

“It was a lot of heat. It was like cement dust, pulverized cement smell, very hot iron, hot steel. You could actually feel it in your teeth a little bit,” Fuller says. “We remember things like being on top of this hot pile of rubble, and a long chain of firefighters and others passing water and fire extinguishers to spray near their feet to keep the ground cool enough to stand on, and there was somebody being rescued at the top of that pile.”

But he didn’t have many other examples to share.

Fuller says most disasters tend to follow a pattern of for every one person killed, nine or 10 may need medical attention.

“It’s a pretty good estimate, but there, it was almost one for one,” Fuller says. “There were a few thousand people who were injured and survived, but it was kind of the wrong ratio. So there weren’t a lot of people to treat. There really weren’t, especially that first evening and first overnight.”

The Man in the Red Hat

Stanley’s group arrived at 388 Greenwich St., known at the time as the Travelers Building, to find ambulances staged. What they didn’t find, still, was any clear direction on triage, where it was, or who was running it.

“So I started doing what I had been trained to do in EMS: Let’s start grouping people first. All the ambulance drivers, gather over here, I need one person to be in charge. Please leave your keys in the ignition and leave your motors off,” Stanley says. “Doctors, I need you over here. If there are nurses, over here. We need somebody to be in charge of this, we need somebody to be in charge of that. Who’s going to be in charge of materials? I’m literally barking out orders, and suddenly, people are asking, ‘What should I do?’ And I’m asking, ‘Well, what’s your training?’ And suddenly, we’ve set up a triage.

Stanley says about an hour later, FDNY Lt. Tom Eppinger arrived to take charge of the communications and materials aspects of the triage.

“And he said, ‘If you don’t mind, I’m going to give you a red hat so you can be the person to help coordinate all the medical effort here,” Stanley says. “Tom Eppinger and I basically ran the triage site. He would say what he thought needed to happen and I would corral the medical people.

“Unfortunately, we ended up only treating less than 20 people. We had maybe three people with chest pain, but the majority of people were covered with dust and we needed to wash out their eyes and give them some food. We had a lot of firemen and police and other people who were collapsed from the heat or the dust, and we basically rehabilitated them too, and they went back.”

The fire lieutenant and the medical student ran a Ground Zero triage site for about five hours.

“There really wasn’t anyone to rescue,” Stanley says. “Eventually Tom Eppinger came to me and said, ‘All right, we have to close this down. They’re consolidating the triage from the Chelsea Piers.’ Everyone was here hoping to help, and it never really came to fruition, other than for those 19 people.”

9/12

The next day saw a shift in focus.

“Responders started to be sick and we could take care of some of the responders: dust in their lungs and their asthma would act up, or dust in their eyes, or a cut or something. We could provide a little roadside care so they could keep working. But as far as injured from the towers coming down, not a lot of people,” Fuller says. “We transitioned to doing some recovery kind of work, looking for bodies and finding some bodies, and helping with recovery for a while. It was kind of cathartic for us a little bit to be at least successful in finding something, even if it wasn’t finding a live person, we were able to find someone and help get their bodies to their loved ones.”

Fuller says his group looked at the soot and debris they brought home in the gear and their clothing with reverence. The boots he wore at Ground Zero remain in the bag he brought them home in, 20 years later.

Solidifying the Path

In 2001 Fuller already had a calling and was well on the path to responding to disasters. Since 9/11 he’s been part of the International Medical Corps response to disasters such as the 2004 tsunami in Indonesia, the 2010 earthquake that devastated Haiti, Hurricane Thomas in St. Lucia in 2010, and the 2013 typhoon that struck the Philippines. He says his experience at 9/11 was an early test that propelled him down that path.

“It definitely broke the seal on attending a massive disaster,” Fuller says. “I’ve taken care of under-resourced, very injured scenarios before and kind of built up a little bit of capacity to do those things. But certainly 9/11, where you couldn’t look around and see any of the world normal, it definitely kind of proved that I would be able to do it and recover and contribute to normal society and then prepare myself to do it again. So it definitely was the first time I had that proving.”

Shortly before the 20th anniversary of 9/11, Fuller left on an International Medical Corps mission to build and run a mobile hospital in earthquake-ravaged Haiti.

‘I Know They’re There’

Stanley says he feels an obligation to tell the story of what happened that day. He’s published his full accounting of his experience.

His biggest takeaway from what he was a part of at Ground Zero was the good he saw in humanity on a day the world saw some of humanity’s worst.

“It’s enormously comforting to know that even when really bad stuff happens, that there are people in a group of a hundred, if you’re in a mall and something bad happens, 90 people will run away from what has happened, but oddly 10 people will run to help. And those people are everywhere,” Stanley says. “Every day when you’re walking the halls, you’re walking by people who will put themselves at risk to help you in an emergency. If there’s anything that helps me sleep better at night, it’s knowing that the world is full of these people. And I met a lot of those people that day. I’m thankful that I met them and I’m sad that it took something as horrible and egregiously bad as 9/11 to meet them. But I know they’re there.”