Diane Sanchez ’95 MS does not just consider herself to be a collector or connoisseur. She’s a steward.

A steward of a specific period of nursing history.

“During my graduate studies at UConn from 1993 to 1995, I took a nursing history course with Eleanor Herrmann,” Sanchez says. “Eleanor loved nursing and history and she gave that love to me. I swooped it up!”

Now Sanchez has given that love back to the School of Nursing — in the form of 15 rare nursing posters from the 1910s and 1920s and over two dozen invalid feeders. The artifacts will be incorporated into the School’s Archives of Nursing Leadership and displayed in the Widmer Wing of Storrs Hall at a future date. The wing is also home to the well-known Dolan Collection of Nursing History.

“The School of Nursing is proud to become the new home for these important pieces of nursing history,” Dean Deborah Chyun says. “We are incredibly grateful Diane thought of us and trusts us to preserve her collection.”

On Aug. 30, the School hosted a reception to welcome faculty and staff back to campus and temporarily displayed some of Sanchez’s posters in Storrs Hall. Sanchez attended the event, along with her family, and shared brief histories of each poster.

Sanchez says she spent about 10 years collecting the artifacts from all over the Northeast. Her husband, Juan, spurred her hobby and research when he found a nursing poster in an antique store in Manchester, Connecticut, and brought it home.

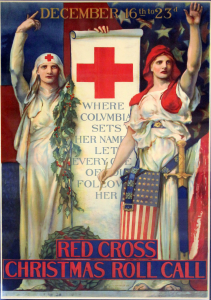

“Most of these posters were propaganda during World War I, 1917 through 1918,” Sanchez says. “They were used to change the mindset of the population in regard to the war. Before the war was declared, this country was neutral, with most of the population against joining to fight with the British and the French.”

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the pinnacle of commercial posters, both in their influence and their artistry, which were fully in evidence in World War I recruitment posters for nursing and the Red Cross. They also constitute a distinct category of artifact — ephemera — because their transitory purposes led most of them to be discarded after they were used.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the pinnacle of commercial posters, both in their influence and their artistry, which were fully in evidence in World War I recruitment posters for nursing and the Red Cross. They also constitute a distinct category of artifact — ephemera — because their transitory purposes led most of them to be discarded after they were used.

Well known, of course, are the advertising posters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec featuring the entertainers of famous nightclubs in Paris. In their time they were no more valued than a billboard is today, but they are now prized in the collections of major art museums.

As the Library of Congress explains about its collection of nearly 2,000 posters: “During World War I, the impact of the poster as a means of communication was greater than at any other time during history. The ability of posters to inspire, inform, and persuade combined with vibrant design trends in many of the participating countries to produce thousands of interesting visual works.”

Although some posters employed traditional motifs (for example, the allegorical figure of Columbia or religious iconography), the bold commercial designs rendered in Impressionist style capture our attention.

Howard Chandler Christy, creator of the “Christy girl” (as iconic as the earlier “Gibson girl”), is perhaps the best known of these artists. Meanwhile, James Montgomery Flagg designed perhaps the most famous poster of the era: the often reproduced and even more often parodied image of Uncle Sam proclaiming, “I want YOU for U.S. Army.”

Although these posters were reproduced in large numbers at the time, they were considered disposable, and most were discarded after the war. Sanchez’s collection, therefore, is a rare trove, representing the emergence of modern nursing as nurses transformed themselves from Victorian domestic workers to health care professionals through national service and advanced education.

Although these posters were reproduced in large numbers at the time, they were considered disposable, and most were discarded after the war. Sanchez’s collection, therefore, is a rare trove, representing the emergence of modern nursing as nurses transformed themselves from Victorian domestic workers to health care professionals through national service and advanced education.

Invalid feeders, and similar devices called pap boats, were used to provide fluids to infants and weakened patients before intravenous therapy was universally available. The half-open, pear-shaped vessels have a handle at one end and a spout at the other to allow caregivers to gently administer oral nourishment and medication.

“I didn’t know they existed until Eleanor brought some to class one day,” Sanchez says, but her interest in them grew to the point that she researched and co-authored an article with Herrmann titled “Feeding Infants, Invalids, and the Infirm,” which was published in the Western Journal of Nursing Research in August 1997.

Their article states: “Known to have existed as early as the 17th century, most of the vessels were produced before the turn of the 20th century. Although occasionally used as late as World War II, they are rarely used today. Consequently, both types of vessels have become sought-after collectors’ items, not only for their immense variety and aesthetic appeal, but for their significance as hallmark artifacts of an era in nursing care.”

Sanchez says she knew she wanted to be a nurse as early as third or fourth grade. “I wrote an essay about it,” she says. “I remember I couldn’t spell the word ‘nurse’ and had to look it up.”

Sanchez began her nursing career as a licensed practical nurse at St. Francis Hospital in Hartford. She then became a registered nurse after studying at Mohegan Community College (now Three Rivers Community College) and earned her Bachelor of Science in nursing from Central Connecticut State University. When she decided to continue her education at the graduate level, she came to UConn — earning her master’s in 1995 and returning for a one-year graduate certificate program from 1996 to 1997.

Sanchez began her nursing career as a licensed practical nurse at St. Francis Hospital in Hartford. She then became a registered nurse after studying at Mohegan Community College (now Three Rivers Community College) and earned her Bachelor of Science in nursing from Central Connecticut State University. When she decided to continue her education at the graduate level, she came to UConn — earning her master’s in 1995 and returning for a one-year graduate certificate program from 1996 to 1997.

Although she has since retired from nursing, Sanchez carried her love for the industry through the curation of her historical collection.

“It really became a passion of mine,” she says. “These posters and invalid feeders used to make me smile, but I’m a different person now. I wanted to make sure they stayed with a nurse. I’m a steward of this part of nursing history and now UConn has become the steward.”

To learn more about the School of Nursing’s historical collection, visit nursing.uconn.edu/archives-of-nursing-leadership.

Follow the UConn School of Nursing on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or LinkedIn.