It’s nearly two months now since a magnitude-7.2 earthquake devastated Haiti, placing severe limitations on an already challenged health care infrastructure.

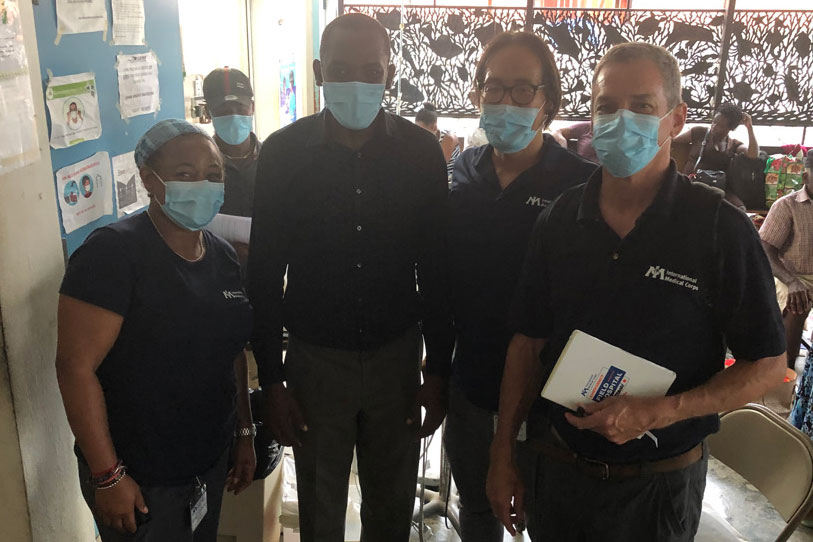

Several international relief organizations have responded, and among those answering the call was Dr. Robert Fuller, UConn Health’s chair of emergency medicine.

There’d be 100 people waiting at the gate hoping to be seen. — Dr. Robert Fuller

Fuller is back after a three-week deployment with the International Medical Corps, which set up a medical clinic on a soccer field about a quarter-mile from a hospital in Aquin. Aquin is a port city on the south coast of Haiti’s Tiburon Peninsula, not far from the epicenter.

“It’s known as a referral hospital for the area, a small hospital that usually could do surgeries, prenatal care, maternity care, C-sections, HIV treatment, malnutrition, malaria — a kind of general hospital as well as a resource for those specialty needs,” Fuller says. “Because of the earthquake, one of its two main buildings could not be occupied.”

When Fuller arrived in Aquin Sept. 9, IMC tents already were in place, not only on the soccer fields but also in the parking lot of the hospital, designated for pre-operative and post-operative care. The hospital’s operating rooms were functional, but the areas for pre-op and post-op were too damaged. Other habitable portions of the hospital such as conference rooms and nonclinical areas were converted into inpatient rooms to start re-establishing its capabilities.

Back at the soccer field, the tent clinic would treat or triage sometimes 170 people in a day, Monday through Saturday. Fuller was in the familiar role of medical coordinator for the facility, which the week prior had been run by expatriate volunteers.

“A typical day, I’d meet with the medical team about the day then around 8:15 we’d open the tents, get the vents and doors open, get the generators going, and there’d be 100 people waiting at the gate hoping to be seen,” Fuller says. “A triage nurse would go through the crowd to determine who needed treatment first, who was most sick. I’d work with a charge nurse to set up staffing for the tents, including translators, nurses, doctors, and midwives to take care of patients all day.”

Fuller also would arrange transfer of patients who needed more advanced care than what was available onsite, a daunting task that became a little less daunting over time.

“I had to find a place, and figure out how to get them there — which was challenging, especially in the first few days — and the last piece was to establish a reliable resource list, traveling around the countryside, finding out who could do what,” Fuller says. “Little by little the existing infrastructure started to re-establish itself with its capability. Within a two-hour radius, I visited all the hospitals and health care facilities to see what their capabilities were. Over the three weeks, little by little hospitals were starting to be able to do what they used to do, even if in a slightly different way, the same service line even if it wasn’t the same structure.”

At the same time, Fuller’s charge was to recruit local nurses and doctors who could sustain the operation for the next several months, while not poaching talent and creating staff shortages at other facilities. When he left Oct. 1, he had hired two physicians and six nurses. IMC still has some supervisory people on the ground, with local providers carrying out most of the patient care.

“For more than 15 years, Dr. Fuller has been an integral part of International Medical Corps’ emergency response efforts in crisis areas around the world,” says Margaret Traub, IMC’s head of global initiatives. “We were fortunate to have Dr. Fuller return to Haiti with us after the most recent earthquake, to help run our mobile field hospital near the epicenter. His prior knowledge of Haiti and its people proved invaluable.”

Fuller says the efforts were well received by the residents.

“The people in Aquin were very welcoming, and very appreciative,” Fuller says. “Even if we couldn’t provide what they needed, they overwhelmingly appreciated our presence. I’d work with a translator, finish a conversation with a patient, and the translator would say, ‘They want to thank you so much for being here, they appreciate it.’ Some had problems we couldn’t help with, and even then, they would still be appreciative.”

Running water is a real privilege.

He describes the living conditions as “rough and tumble,” with little relief from the heat, no air conditioning, no screens on the windows. He and many of the providers stayed at a local hostel, which did have running water, although neither the water service nor the electricity was consistently reliable.

“The fans would go off, and it would get pretty warm. Running water is a real privilege,” Fuller says. “Nobody in this area has running water in their homes. Everyone’s carrying a big yellow canteen or bucket, taking it to a hand pump to fill and bring home. Our water would go off sometimes for 12 hours a day, which was an inconvenience that brings you more in tune with the local population to experience their struggles. Still, it was nice as a building, not damaged by the earthquake, and I felt pretty comfortable going there and camping on one of the balconies.”

Fuller is no stranger to emergency care beyond the walls of the UConn John Dempsey Hospital Emergency Department. On 9/11, he was part of a special operations unit UConn Health sent to the World Trade Center site, and was part of several IMC disaster responses, including the 2004 tsunami in Indonesia, another earthquake in Haiti in 2010, Hurricane Thomas in St. Lucia in 2010, and the 2013 typhoon that struck the Philippines. This trip to Haiti was his first since the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s the kind of thing I would normally respond to, and the COVID vaccine makes it possible to take part in these humanitarian missions again,” Fuller says. “I find I get satisfaction working through puzzles that are these complicated assignments. I feel like it’s something I’m good at, and it’s rewarding to be able to help.”

He says his experiences in such limited-resource environments reveal the stark differences in how to provide care.

“I have to not just manage the one problem ahead of me, but to think about the context and how that context influences all the medical decisions you have to make,” Fuller says. “What if I move this patient to a new location, would the care be delivered appropriately? Would the patient survive? Would they have access to food and water if they left their social network? Can we help the social network stretch out to reach where they’re landing? The questions beyond the medical question. It’s interesting to think so many moves down the field, sometimes you come to the conclusion the best place to get care is here at the tent hospital.”