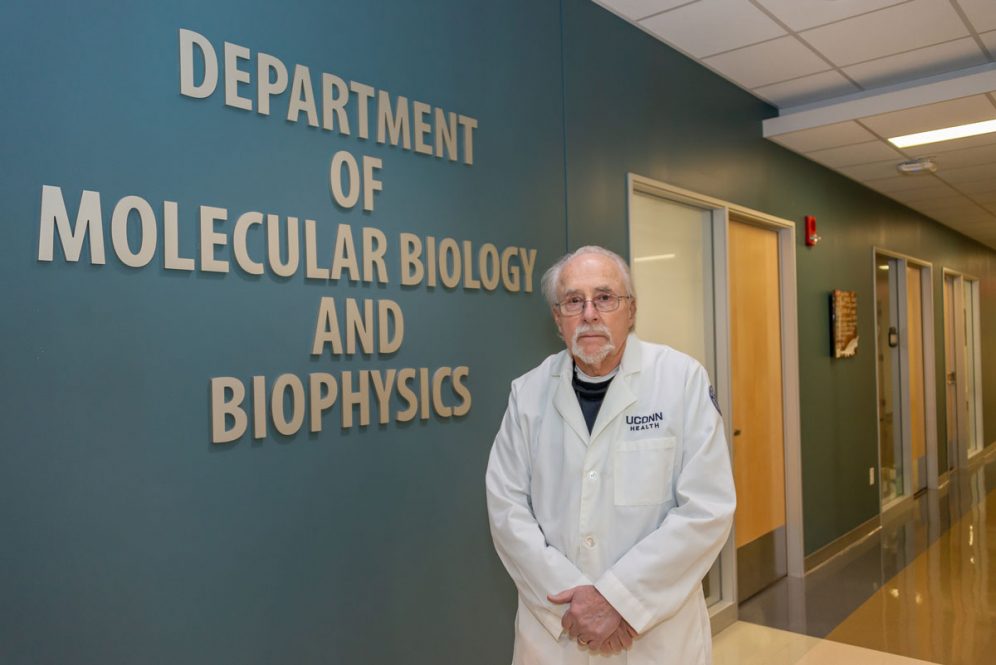

He’s UConn Health’s longest-serving employee. It was the summer of 1971 when Peter Setlow started working in a trailer as an assistant professor in what was then known as the Department of Biochemistry. Over the next five decades he would become assistant professor, then full professor, serve a seven-year stint as the chair of the Department of Biochemistry, and since 2005 he’s held the title of Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor in the Department of Molecular Biology and Biophysics.

Setlow estimates that over his 50 years at UConn Health, the number of lab technicians, lab assistants, graduate assistants, students, and postdoctoral fellows who’ve worked in his lab is in the hundreds, and he conservatively estimates the amount of grant money he’s brought in exceeds $20 million.

Earlier this year UConn Health recognized Setlow for his 50th-year-of-service milestone. UConn Today asked him to reflect on his time and share some of his observations.

What was it like when you got here in 1971?

This place was very different then. This building [the L building] wasn’t open yet. When I came in, everything was down the hill where Jackson Labs is now. I was in a trailer. I was in there for a year, in a trailer that had been outfitted as a lab, very minimally, and I was separate from the rest of the department; they were in Butler buildings that were all sort of cobbled together. So if I wanted to go to the department where most of the equipment was, I had to go outside — fine during the summer, but it was a pain in the winter. And the pipes froze in the winter because they weren’t insulated down below. But we survived.

You could walk outside and look up the hill and see this new building. The shell was all there. There was something up there; it was hope for the future.

And my department — then it was biochemistry — was the first one to move up here [L building] in the summer of 1972, and that was interesting because there were some things that hadn’t been fixed, but it was a hell of a lot better than the Butler buildings, especially in the winter, because those Butler buildings were cold and very crowded. And so, it was really nice to get up here.

What brought you to UConn Health?

I wanted to run a lab. I had some things that I picked out to start working on. That’s changed a lot of course, over 50 years, but I wanted to work in a lab and climb those golden stairs and do all kinds of great things in science. I came from Stanford University, the biochemistry department, in the California Bay area, drove across the country with my wife, who was then pregnant, in a VW beetle, it was a good time.

I came here because I wanted to come back to the East Coast. My wife, who was from the Midwest, didn’t want to go back to the Midwest for love nor money, and I didn’t want to be in a big city. I wanted no part of a big-city school. I didn’t even go look. I wanted to come back to the East Coast.

I was born in New Haven and I grew up in New Haven. I went to high school there, my father was at Yale on the faculty. And then we moved to Oak Ridge, Tennessee — a little different than New Haven, but there’s a big national lab there. My dad was offered a big position and my mother was also in science and she was going to have her lab there too. So it was a big deal for them.

I wanted to come here because I liked the place, I liked where I would be, where I could live, five minutes from the lab. We ended up buying a house in Farmington that is five minutes from the lab. We moved in in 1972, and we’re still there.

I like doing research, looking at data is still fun. Trying to puzzle out what the data mean and what to do next is fun. I enjoy it. — Peter Setlow

How did those early years go for you?

I had five publications, not huge big papers, but they had my name numero uno on them, that were published from work that I did in that trailer, almost all by myself. The last few months I had a graduate student who had started in my lab and she helped. So I really felt good about it.

One of the things that I did caused quite a stir in the field. It shouldn’t have, but it did. For a long time, it was one of the most cited things I’d ever done, essentially saying that there is none of a particular compound (cyclic AMP), that was really a big thing in the bacterial world at that time, and me just saying, “Nope, it’s not in this organism at all.” And that went against the dogma. I was right as it turns out. So I professionally, I did quite well.

Before I left Stanford I had started a grant that was recommended for NIH funding. I had that to start essentially once I got up the hill, so I could hire a technician and on and on and on. So when I got up the hill, I had a graduate student and I had a technician and my career really took off.

If someone told you in 1971 you’d still be here in 2021, how would you have reacted?

Oh, I would have laughed at that. When I came here, the only option we had in terms of retirement was the state retirement. It was something like, if you leave before 10 years, the state’s not going to give you their contributions. And I said, “I’m not going to be here in 10 years.” I’d been in college for four, graduate school for four, postdoctoral for three, three different places. I’m not going to be here. So we didn’t even sign up for it.

Then one day you look up and you’ve been here 50 years. I’ve had opportunities to leave. I looked, there were some things here I was unhappy with. So when I looked, I looked at four different places, and always decided that the grass was not greener. I had offers from three and I turned them down.

How have you spent your time away from the office and lab?

I got very heavily involved in coaching soccer. I played soccer in college. Then I watched my daughter’s team get destroyed. I started coaching my son a little bit, but he wasn’t really interested in playing. Then I started coaching my daughter and I coached her for 10 years, which was great. I got to know my daughter better than most fathers ever do. It was phenomenal. I enjoyed coaching her and being with her. We took a team to Scotland for an exchange program. We were there for two weeks and my daughter had a blast. And a number of the kids that I coached came and worked in the lab in the summer, which was really great. One became a graduate student here and is now teaching in the Farmington school system.

A big deal was just made because they named a field after me. There’s a group of outdoor fields called Tunxis Mead. A new turf field was put in and they named the field after me. There was a big dedication ceremony right in front of the field, and there were about 75 to 100 people there — some people from here, a lot of former players and some people I coached with. It was really very touching to me. And my daughter actually flew up from Florida, where she’s on the faculty at the University of Florida. My wife even came, and she has no interest in soccer. I did it for 44 years, recreational league initially, then travel, mostly girls, the last six or seven years with boys, but I wasn’t a head coach anymore, I was an assistant for those teams. But I’ve coached travel and won the state championship six times, a lot of tournaments. The great majority were wonderful kids. I had a wonderful time. And I still hear from a lot of them. It was a lot of fun. It was great to be here working here for eight, nine hours and then go down and coach and yell at a bunch of kids, great for stress relief.

What are you most proud of from your 50 years at UConn Health?

That I’ve always done really good research, utilizing all kinds of new — new to me —technology. There are a lot of people that do the same thing over and over and over. And I’ve done some of that. Everybody does the low-hanging fruit, but I’ve consistently utilized new and upcoming technology for my research. I may not do it in my lab, but I find people to collaborate with to do it. And that’s been a lot of fun because you suddenly can look at problems in ways that you never imagined. And doing science for 50 years, you see revolutions in science. When I started, there was no molecular biology, it was just coming, so I got to learn it myself, how to do it, how to apply it. And that was difficult because you have to learn new stuff on your own, which is fine, and apply it. It’s phenomenal, and made the problems I was working on, now you can do them in a whole new way. So I’m really proud of that.

I’m also proud of so many of the graduate students I’ve had who have gone on and done really well. And I’m still in touch with so many of them, which is really gratifying, to see I had something to do with their success, and postdocs as well. I’m really proud of them. I mean, not every graduate student I’ve had is having that kind of success, but an awful lot of them have done well, found careers that were right for them.

What keeps you motivated?

I really like doing research. There are other things that we do here as part of this. I mean, I have to serve on some committees and one of them is very time consuming, but it’s a very important committee, which is the promotions committee. We make recommendations to the Dean.

I review papers. I review 40 to 50 every year and I’m an editor for four or five journals or on the editorial board, either or both, because that’s part of you giving back to the community of science and it’s also providing quality control over what makes it into the literature in my field. There’s a lot of trash. I enjoy reviewing papers, even if I’m going to reject them. And I like doing research, looking at data is still fun. Trying to puzzle out what the data mean and what to do next is fun. I enjoy it.

And I don’t know what I’d do if I wasn’t doing this.

Setlow, 77, lives in Farmington with his wife of 56 years, Barbara Setlow, who is retired from the UConn School of Medicine faculty. They have two children (one in science) and four grandchildren.