As a human rights major, UConn senior Joseph Vazquez ’22 (CLAS) was familiar with the historic Nuremberg Trials and knew about the late Connecticut Senator Thomas Dodd’s role prosecuting Nazi war criminals after World War Two.

“I knew about Nuremberg,” he says, “and I’ve worked with the Dodd Center, so I’ve learned about the history of Thomas Dodd. But mostly all on the surface level.”

That changed, though, when Vazquez enrolled in a human rights class that called for a deep dive into Dodd’s very personal account of Nuremberg and a one-semester crash course on using historic archives to tell stories through film and digital media.

“This class really put a first-hand perspective on it,” says Vazquez, “because I was looking at these images, these personal documents, these letters from Tom Dodd of his accounts while he was in Nuremberg, and it’s just really fascinating to see what’s going through somebody’s mind who’s in that situation. The horrors that are associated, the fears, the anxiety, in some cases the joy – the happiness that is felt knowing that this is important work – it allowed me to see Nuremberg from a deeper perspective, but also from a different perspective, an inside look.”

Vazquez and his classmates in the course Visual Storytelling through Human Rights Archives spent a semester reading and categorizing Dodd’s numerous letters – written to his wife, Grace, during the 18 months that he was away from his family during the trial – and sifting through other archival footage and documents related to the Holocaust and the Nuremberg Trials.

The result of their efforts is a 13-minute film that takes the viewer on a journey through the events of the first tribunal through Dodd’s words and experiences. The short film, entitled “Letters from Nuremberg,” was first screened as part of the Human Rights Institute’s Human Rights Film+ Series in October.

“Nuremberg was a foundational moment in the evolution of human rights,” says Catherine Masud, an assistant professor in-residence at the School of Fine Arts Digital Media and Design department, jointly appointed by the Human Rights Institute. “It was momentous at the time in establishing standard legal principles for the prosecution of human rights violations relating to mass atrocities and genocide, and that’s continued to reverberate through the subsequent decades.”

A documentary filmmaker who has worked significantly with archives and archival footage throughout her career, Masud conceived the course and launched it as a way to introduce students to the power of archives as a vehicle for learning about human rights and about the power of communicating about human rights through visual media.

“I’ve made a number of historical films, documentaries, that utilized a lot of archival footage in the storytelling,” she says. “So, this was a way to introduce students to history and to get them to appreciate the importance not just of archives that relate to human rights, but also personal archives as being a very subjective perspective or personal perspective on those historical events.”

UConn is home to several significant collections of human rights archives, including the Dodd Papers, which are maintained by the UConn Library’s Archives and Special Collections. Much of the Dodd collection has been digitized, which gave Masud’s class – which was conducted virtually during the Spring 2021 semester – access to much of the materials they used while working together remotely.

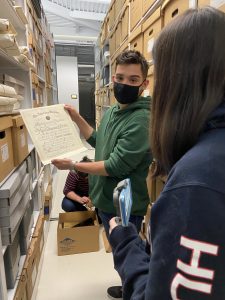

“We did actually organize one visit to come to the Dodd Center, to go into the archives, and most of the students participated in that,” Masud says. “I thought that that was very important. They came away from that feeling that it was much more real. But even then, I think because we were dealing with mainly digital or digitized material, it was also possible to do this as a virtual course. We could share screens, we could look at things together, and we could review the different archival holdings, going to the UConn Library Archive website and viewing it that way collectively.”

The students also gathered archival footage of the trials recently made available by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, and interviewed Thomas Dodd’s son, Connecticut Senator Christopher Dodd, about his father’s role in the trial and legacy in human rights.

“We had an immense folder of material that was just sorted into categories – images, pictures of the Dodd family, pictures of UConn – and our role was to see what we were going to do with it,” Vazquez says. “What are we going to use this for? We already had access to the archives. Now what?”

The students focused on Thomas Dodd’s letters, his personal observations, and his critical moments in the trial to tell their story of Nuremberg. With permission and through the generosity of the Dodd family, they were able to use images of Thomas Dodd’s own handwritten letters to help enhance the personal feel of the film.

“The family had not agreed to make those public before,” says Masud. “But they were very gracious in agreeing to allow the library staff to digitize some of the letters that we were interested in using in the film, and I think it really adds a lot to it, and I’m very grateful to them for that, because I know it’s a very personal thing.”

Vazquez says that the remote nature of their work created unique challenges for the small, collaborative group, but it also offered the opportunity for them to capitalize on the skills they each brought to the table – and to learn what else they could achieve.

“I had some of the hard technical experience,” says Vazquez, an experienced audio producer who works at the campus radio station and has completed an internship with Connecticut Public Radio. “But when it came to script writing – I was placed on the script team and I’ve never, ever had experience writing a storyboard. And I loved it. I think I developed more of a passion for storytelling.”

He continues, “As corny as it sounds, you never know your strengths until you’re put on a team where you’re all faced with this much work. We learned who was good at what – who was good at organizing and getting all the stuff. Like, hey, we made this scene, we’re looking for a visual that can help match it. We have somebody who was amazing with all the documents that we had, and they were able to find it. So, you never know where your strengths can be utilized.”

Masud says that the experience with the Nuremberg course has helped to guide its next iteration – it’s been relaunched as a two-course sequence called Human Rights Archives, with the first sequence introducing students to the archival process as a way of curating community memory, and the second focused on using the archive for visual storytelling on human rights-related themes. That sequence, currently underway, is focused on telling stories of the Armenian community and the multi-generational impact of genocide within the community.

“Students are learning all about conducting oral history interviews, digitization processes, and also methods of cataloging and curation for archival materials,” says Masud. “Then, the next semester will actually be the documentary storytelling around those materials.”

To learn more about human rights educational and advocacy opportunities at UConn, visit humanrights.uconn.edu.