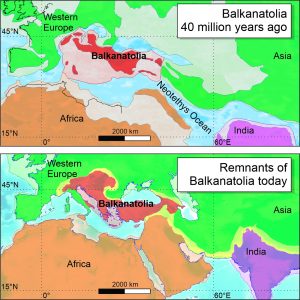

A team of French, American, and Turkish paleontologists and geologists, including UConn researcher Megan Mueller, has discovered the existence of a forgotten continent they have dubbed “Balkanatolia,” which today covers the present-day Balkans and Anatolia. They believe that it enabled mammals from Asia to colonize Europe 34 million years ago. Their findings are published in the March 2022 volume of Earth Science Reviews.

For millions of years during the Eocene Epoch (55 to 34 million years ago), Western Europe and Eastern Asia formed two distinct land masses with very different mammalian faunas: European forests were home to endemic fauna such as Palaeotheres (an extinct group distantly related to present-day horses, but more like today’s tapirs), whereas Asia’s population was more diverse, including the mammal families found today on both continents.

“The Eocene fossils found in Turkey are bizarre,” says co-author and UConn Department of Geosciences researcher Megan Mueller. “We found fossils of European mammals that migrated to Turkey before 50 million years ago, then were stranded there and subsequently evolved in isolation. From this period of isolation, we found fossils of African and Asian mammals that miraculously made it to Turkey from by crossing wide oceanic barriers.”

Mueller explains the “Grande Coupure” is a famous event at the end of the Eocene, 34 million years ago, when Asian mammals arrived in and essentially took over western Europe.

“This faunal turnover is often attributed to the connection of landmasses due to the dramatic sea level drop from the growth of Antarctic ice sheets,” she says. “Yet, there is fossil evidence of Asian mammals arriving in southeastern Europe 5 to 10 million years earlier, which calls into question when and how Asian mammals colonized Europe. Our latest fossil finds shed light on this question.”

The team has come up with an explanation for this paradox. To do this, they reviewed earlier paleontological discoveries, some of which date back to the 19th century, sometimes reassessing their dating in the light of current geological data. The review revealed that, for much of the Eocene, the region corresponding to the present-day Balkans and Anatolia was home to a terrestrial fauna that was homogeneous, but distinct from those of Europe and eastern Asia. This exotic fauna included, for example, marsupials of South American affinity and Embrithopoda (large herbivorous mammals resembling hippopotamuses), formerly found in Africa. The region must therefore have made up a single land mass, separated from neighboring continents.

“At a site in the Çiçekdağı Basin in central Anatolia, we found several fossil mammal teeth and jaw fragments belonging to Asian brontotheres and hyracodontid rhinocerotoids,” Mueller says. “We used several methods to determine that the fossil bed is between 38 and 35 million years old making these the oldest known Asian mammals found in Turkey.”

The team also discovered a new fossil deposit in Turkey (Büyükteflek) dating from 38 to 35 million years ago, which yielded mammals whose affinity was clearly Asian, and are the earliest discovered in Anatolia until now. They found jaw fragments belonging to Brontotheres, animals resembling large rhinoceroses that died out at the end of the Eocene.

All this information enabled the team to outline the history of this third Eurasian continent, wedged between Europe, Africa, and Asia, which they dubbed Balkanatolia. The continent, already in existence 50 million years ago and home to a unique fauna, was colonized 40 million years ago by Asian mammals as a result of geographical changes that have yet to be fully understood. It seems likely that a major glaciation 34 million years ago, leading to the formation of the Antarctic ice sheet and lowering sea levels, connected Balkanatolia to Western Europe, giving rise to the “Grande Coupure.”

“The results are exciting because they show that mammals dispersed along a continuous southern corridor from Asia to Balkanatolia then finally to western Europe,” says Mueller. “The opening of the dispersal route into Balkanatolia was likely tectonically driven and paved the way for the Grande Coupure. There is still a lot of exciting work to be done, including investigating the role of climate change and tectonics in controlling the timing of mammalian isolation and dispersal.”