Chronically stressing the retina can weaken it and damage our ability to see. But retinal cells have a remarkable ability to wall off damage, a team of neuroscientists led by UConn Health reports in the 1 March issue of PNAS. The walling-off or “bunkering” of the damage may be key to preserving our eyesight.

The retina is a delicate tissue in the back of the eye that detects light and transmits images to the brain. Muller glia are very long cells that span the thickness of the retina and provide mechanical strength, supporting the neurons and light receptors that detect light, shape and color.

Muller glia are also involved in protein changes related to retinal injury, being the first cells to respond. UConn School of Medicine neuroscientist Royce Mohan and colleagues have discovered that the endfeet, a specialized zone in Muller cells, is where proteins become modified when the retina is under stress. These endfeet are at the opposite end of the retina, quite a distance from light receptors. The researchers propose in the paper that this segregation of the endfeet and light receptors may permit light detection to continue even as the retina responds to stress.

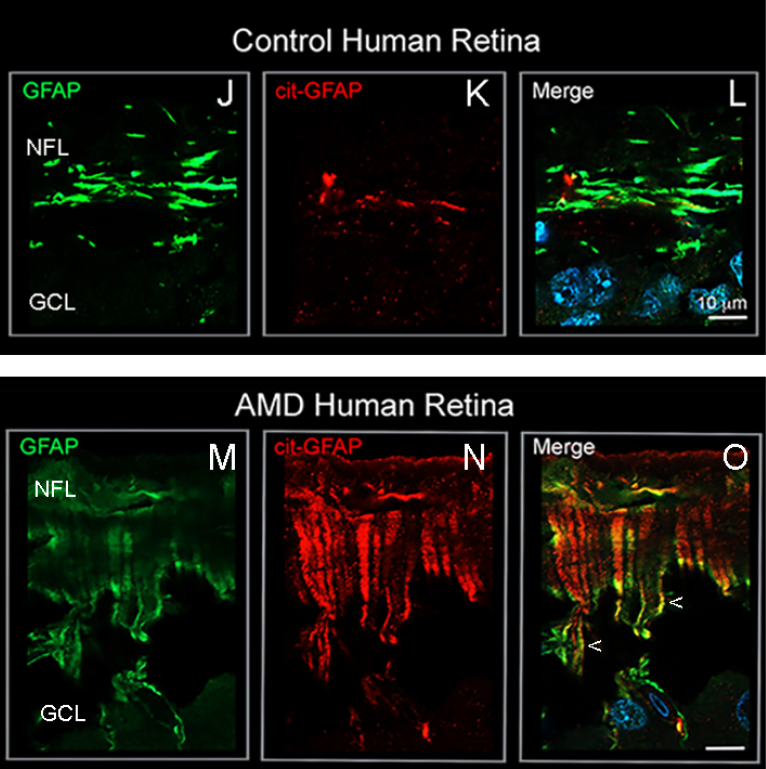

The modification of proteins Mohan’s lab has been studying is called citrullination. In citrullination, the amino acid arginine is changed into citrulline. Because in early stages of stress or disease, the citrullinated proteins stay sequestered in the Muller cells’ endfeet, Mohan calls this area the citrullination bunker. But if this bunker is chronically engaged, then the overabundance of citrullinated proteins reach other parts of the retina. Muller cells in human age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and mouse models of retinal degeneration reveal citrullinated proteins extending beyond the endfeet throughout body of the cells.

Citrullination may have many effects on Muller glial cells which are only just being understood. For example, arginine is positively charged, while citrulline is not. The loss of the positive charges is permanent, and may irreversibly change the flexibility or other mechanical properties of the Muller glial cells. This may cause the Muller cells to become incapable of adapting to fluid build-up when the retina swells up under stress. Alternatively, it’s possible the citrullinated proteins could appear foreign to the body and draw the attention of the immune system, potentially beginning autoimmune disease. Turning off citrullination in the end feet bunker could delay or avoid these problems and preserve eyesight for longer.

This team has also identified that the endfeet citrullination process is controlled by an enzyme known as peptidyl arginine deiminase-4 (PAD4). Small molecule inhibitors of PAD4 have been developed for other types of citrullination-dependent diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Mohan believes that such therapeutic agents could be applied to reduce citrullination at early stages of AMD and spare the retina of undesired responses to this protein modification.

The research was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.