In 1977, John Brittain took a tenure-track position at the UConn School of Law, settled into a new home in Hartford and took a close look at the city’s public schools.

“First thing I did, which is so simplistic but tells so much, was drive around the schools in the morning and see what the children looked like who were going to school and come back in the afternoon when school let out and follow them to their homes to see what their homes looked like,” he said in a recent interview. “And immediately I determined that the Hartford, Connecticut, and surrounding schools were segregated.”

That straightforward observation propelled Brittain into the role of one of the lead counsel in the groundbreaking Sheff v. O’Neill lawsuit, a long and successful challenge to Hartford’s school segregation. After 33 years and a series of court victories and legislative actions, the case culminated late in January with a court settlement that lays out a comprehensive new school choice plan and other remedies.

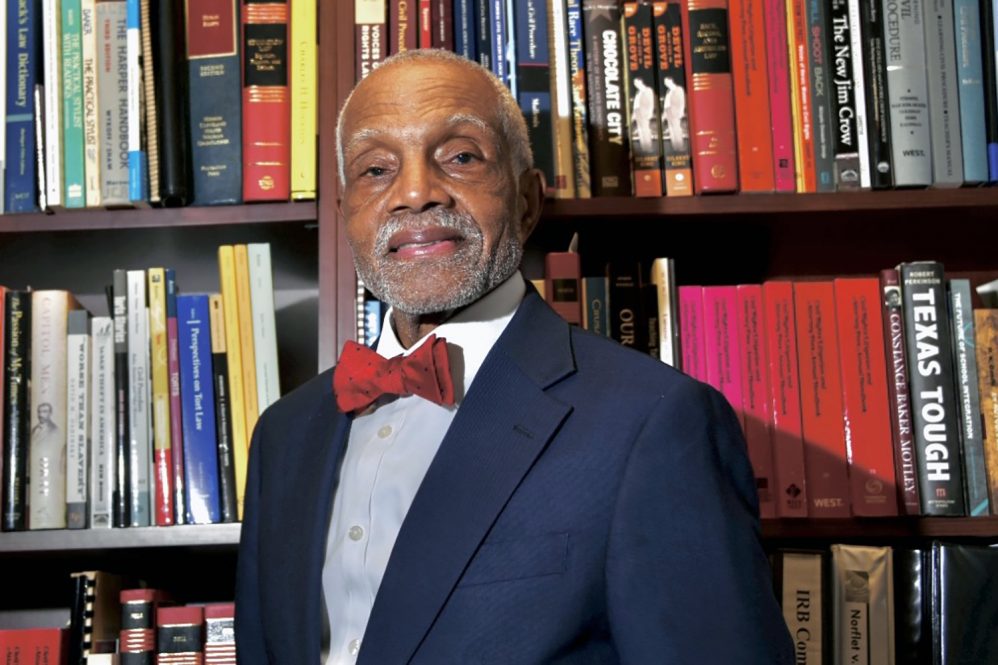

For Brittain, the first Black tenured law professor at UConn, Sheff was a necessary counterbalance to his academic career. He was determined to follow the advice of his mentor, the civil rights leader and Howard University law professor Herbert O. Reid, who told him to “keep one foot in the classroom, teaching in the law school, and the other foot in the courtroom, litigating civil rights cases.”

On March 31, the law school will honor Brittain and his role in the Sheff case in an event titled “Racial Equity In Education: Honoring the Achievements of John Brittain.” The program, co-sponsored with the UConn School of Law Alumni of Color Affinity Group, is part of the law school’s celebration of its centennial year.

“UConn Law is honored to welcome Professor Brittain back to his law school home,” Dean Eboni S. Nelson said. “Professor Brittain’s commitment to impactful teaching, advocacy, and service has served as a role model for me throughout my career in the academy. He epitomizes the values held by UConn Law faculty, both past and present.”

Accepting the job at UConn Law in 1977 was something of a homecoming for Brittain. He grew up in Fairfield County, and attended public schools in Norwalk, where he was the only Black child in his elementary school and the only Black player and captain — and highest scorer — on the Norwalk High School hockey team. He earned a BA and JD from Howard University, where he learned from Reid and other faculty members who had been involved in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education.

After law school he spent four years in Mississippi litigating school desegregation and other civil rights cases, then went into private practice in San Francisco. The call to return to Connecticut was personal, and insistent. Reid was lobbying for Brittain to become a law professor and take on civil rights cases. And Brittain’s best friend, Aetna executive Sanford Cloud, had agreed to help UConn Law Dean Phillip Blumberg lure Brittain back to Connecticut.

“He said, ‘John it’s time for you to come home. It’s time for you to come back to the University of Connecticut and become a law professor,’” Brittain recalled.

As Brittain and the rest of the Sheff legal team prepared to file suit in 1989, pressure mounted on the law school’s dean at the time, Hugh Macgill, to restrain or even fire Brittain. Some members of the legislature were particularly incensed.

“They didn’t like the law school and the state of Connecticut paying for me to be a law professor at the University of Connecticut and suing the state of Connecticut,” Brittain said. He recalled Macgill telling the critics that Brittain was fulfilling his responsibility to perform public service.

In 1995, a Superior Court judge ruled against the plaintiffs in a decision that marked the low point of the case for Brittain. The high point came the next year, when the Connecticut Supreme Court reversed that decision and initiated more than two decades of proposals, plans, negotiations and remedies to school segregation and racial isolation.

In 1999, Brittain left UConn Law after 22 years on the faculty to become dean of the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University in Houston. He believed the Sheff case was proceeding well and that charter schools and other remedies were starting to make a difference. He credits the remainder of the original legal team, and the lawyers who joined later, with bringing further progress in the settlement reached earlier this year.

The March 31 event will bring many of the original legal team back together, including Martha Stone, who is now executive director of the Center for Children’s Advocacy; Philip Tegeler, executive director of the Poverty and Race Research Action Council; and prominent Connecticut appellate attorney Wesley Horton. Elizabeth Horton Sheff, the plaintiff on behalf of her son Milo Sheff, will also speak at the event.

Brittain said he is looking forward to the reunion — and to watching the progress in desegregation stemming from the latest settlement. It may take years to see definitive proof that the remedies are working, he said. The measure will not just be reducing racial isolation in schools, he said, but also “raising the achievement level for children of color.”