In 1991 in Pakistan, there was a surge of women being burned.

A stove would burst, the official report would say – a terrible accident – and only the young bride of the family would be injured or, more often, killed.

“It was very intriguing for me,” says Marvi Sirmed, a journalist and activist who was one of the rare young women working at a newspaper in Pakistan at the time. “When I started digging, first they said, ‘Oh, you know, because in the kitchen, only the daughter-in-law works, so everyone else remains unhurt.’”

Most newspapers in Pakistan at that time employed only one woman, says Sirmed, and that woman was known as the “lady reporter” who would exclusively write for women. Articles about the latest fashions, or recipes, or romantic short stories were the sorts of topics that women in the patriarchal society should be reading, according to the men who ran the newspapers.

Sirmed, who was working as the editor of her newspaper’s weekly women’s edition, felt otherwise.

“I kept digging for four or five months for this story, and some of these incidents would be accidental,” she says, “but most of it was because the daughter-in-law did not bring enough dowry. So, it was a dowry killing, or an honor killing, concealed into accident.”

Her enterprising journalism was not welcomed.

“I brought several stories of the survivors of these ‘accidents,’ and my editor just refused to entertain that,” she says. “He said that women buy the women’s edition because they want to read more about the pleasant subjects. But what you are doing is exactly what they don’t want to know and what we don't want to put in our publication, because these are not pretty faces. If you want to do a modeling session with a high-ranking model girl who would display good apparel, we are all for it. But these faces of burned women, it’s absolutely a ‘no’ story.”

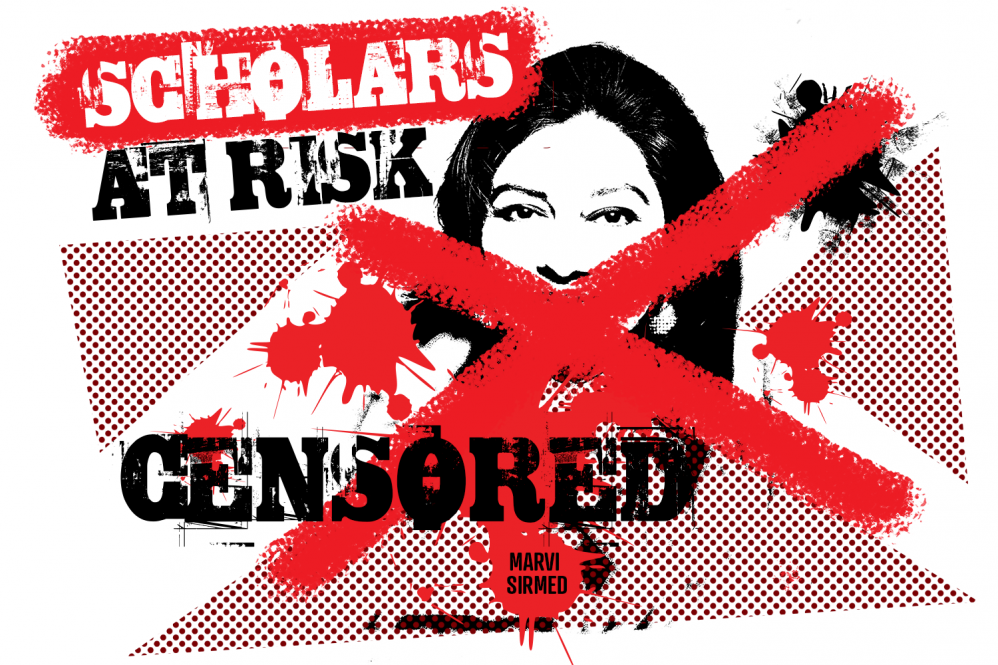

The stories of the burned women were far from the last time Sirmed would face opposition, controversy, harassment, personal attacks, and outright violence for the stories she wanted to tell and the light she aimed to shine on some of the darkest corners of Pakistani life and governance.

In fact, she’s still telling those stories, and working as an activist for change in Pakistan and other South Asian countries, though she’s now more than 7,000 miles away from her home country, in the United States and teaching at UConn through the University’s longstanding and unique partnership with the international network Scholars at Risk.

“It’s at the very heart of a university’s mission to advance knowledge and to advocate for academic freedom,” says Kathryn Libal, an associate professor of social work and human rights at the UConn School of Social Work and the director of UConn’s Human Rights Institute, or HRI.

A Network to Safety

Since November 2010, UConn and HRI have worked to help support that mission as part of the Scholars at Risk Network, or SAR. Established in 2000, SAR assists academics who face persecution by arranging short-term positions for them at host universities around the globe.

Libal and other faculty affiliated with HRI established the UConn chapter of SAR with support from the Office of Global Affairs and the Provost’s Office, and HRI has engaged interdisciplinary partnerships from within the University – including the departments of Political Science and Dramatic Arts and El Instituto – to help support the efforts of some of its scholars.

“The University of Connecticut is deeply committed to the Scholars at Risk program and the remarkable individuals that we host,” says UConn’s Vice President for Global Affairs Daniel Weiner. “These scholars remind us every day of the importance of practicing human rights with vigor and resolve.”

Over the years, HRI has partnered with SAR, the Institute of International Education’s (IIE) Scholar Rescue Fund, IIE’s Artist Protection Fund, and the National Endowment for Democracy to identify and support at-risk scholars and practitioners needing a host institution. The University also is part of the New University in Exile Consortium, and HRI is working with the Open Society University Network’s Threatened Scholars Integration Initiative to develop more opportunities to host scholars and practitioners in the future.

“The scholars hosted through SAR represent all disciplines,” explains Libal, a champion of the network who also serves on the organization’s steering committee for the U.S. “They might be physicists. They might be political scientists. They might be molecular cell biologists. And in their home countries, they are persecuted because of their research or teaching. SAR is a global institutional response that supports scholars and practitioners so that they have the freedom to think and exchange knowledge.”

Since becoming a part of the network, UConn has hosted scholars from Mexico, Iran, Syria, Ethiopia, Turkey, Nicaragua, and now Pakistan. While SAR fellowships may be offered for just one semester, Libal says it quickly became clear to UConn that the scholars needed more time in residence.

“In the beginning, we thought we were giving people a respite of a semester and learned very quickly that wasn’t supportive enough of scholars who had been displaced,” she says. “We increased the residence to a year, and even then that wasn’t enough for people to really situate themselves and to be able to get back to their writing, understand the academic job market, or begin retraining if needed. So, we advocated for longer residencies.”

UConn’s scholars stay upward of two years, she says, which gives them time to address a number of unmet needs while gaining their bearings in a place of safety.

“It’s not just about having a scholar figure out how to write for U.S. journals,” Libal explains. “Many haven’t had access to good health care for some time. Some have experienced trauma and have latent health challenges. So quite honestly, having a couple of years to address health needs is really critical.”

UConn can offer this support to its SAR scholars, Libal says, because the entire University community – from the president and provost to the faculty and students – have embraced the network’s mission and goals, and have put the structure and resources in place to make the program successful.

“UConn is deeply committed to our human rights mission, with this program serving as a powerful example of the impact we can have,” says Carl Lejuez, UConn’s provost and executive vice president for academic affairs. “It is inspiring to work with colleagues who are dedicated to creating and supporting a haven for these vulnerable scholars.”

“SAR is grateful to count UConn among the most active and committed hosts of SAR scholars in the United States,” says Rose Anderson, SAR’s director of protection services. “In addition to UConn’s overall commitment to hosting at-risk scholars and practitioners, Kathy Libal, SAR’s primary representative on campus, takes many extra steps to ensure that visiting scholars and practitioners at risk are well-supported in the academic and personal spheres, offering support for networking and professional development, helping them to navigate the challenges they might face while on campus, and supporting them to plan for what is next after the SAR placement comes to a close.”

The SAR network has over 550 members in 42 countries, to date. Each year, SAR works to place more than 100 at-risk scholars so that they can escape dangerous conditions and continue their academic work in safety.

“Given UConn’s years of experience and skill in hosting, we have frequently asked UConn to participate in workshops for SAR hosts and scholars to impart their perspective on host support needed for a visit be as successful as possible,” Anderson says. “In this way, UConn inspires other campuses to become involved.”

Because of the increasingly high demand for assistance, SAR focuses its efforts on scholars facing the most immediate and severe threats, including threats of violence, torture, and wrongful imprisonment or prosecution – scholars just like Marvi Sirmed.

When the Threats Come

When, as a budding journalist, Sirmed asked to start reporting on politics, she was slut-shamed by the male reporters who worked in the newsroom.

“It was very difficult, because if you are sitting in the newsroom with all the male reporters, they would be 100 percent sure that you are making yourself available for them, and you are fair game,” Sirmed says. “Sexual harassment was not even a word back then. It was considered a fact of life that a woman has to endure – to tolerate harassment – if a woman decides to move out of the four walls of the house.”

Sirmed left reporting and started working as a columnist, because it didn’t require her to go to a newsroom – she could instead work on her stories on her own time. She spent the next 20 years working as a columnist, often writing about political issues and terrorist organizations and advocating against human rights abuses in Pakistan.

She also worked for the United Nations Development Program in Pakistan as an expert on democracy and parliamentary institutions. And while she says the U.N. was supportive, Sirmed’s outspoken activism did not earn her many friends from within the Pakistani government, the military establishment, or the active extremist groups in the country.

In 2012, Sirmed survived an assassination attempt, when unidentified gunmen fired several shots at her and her husband, Sirmed Manzoor, who is also an investigative journalist, in the capitol city of Islamabad. They were unharmed.

“That was one point in time where we seriously considered leaving Pakistan,” she says. “But we did not. Even at that time, we did not.”

She did ultimately leave her position at the U.N. and began working as a consultant, offering research and writing services to international organizations and using any profits to support victims of terrorism, especially women.

“There were very many destitute women who were left because of the terrorism in Pakistan,” she says. “For lack of education, skills, and job opportunities, many of them were pushed to abject poverty or were left at the mercy of the extended family, when they were not opting for suicide.”

And she kept writing. In 2017, Sirmed began working as a special senior correspondent for the Daily Times, an English-language newspaper, covering topics including human rights, violent extremism, and terrorism in Pakistan.

“That was a hard area to report for women reporters,” she says. “Women had started reporting on politics, but terrorism was an area that was considered a male domain. Reporting on that area makes many enemies, and that’s where I made my very strong enemy of the Taliban.”

Her home was ransacked multiple times – computers, passports, and other personal items taken. She was publicly slut-shamed while simultaneously being called an angry, sexless feminist. Threats were made against her family, including her young daughter. Her personal phone number and email were posted online, leading to harassing and threatening messages. Personal details about her family members, including her parents, were also distributed online, alongside calls for them to be attacked.

“They were not only threatening my life, they were attacking my integrity,” she says. “Living in Pakistan and working as a journalist and an activist was a continuous trauma.”

Threats were also made against the publications that she wrote for. Sirmed began to self-censor what she published in the newspaper, she says, out of fear of what might happen to others within the organization.

“When the threats come, it’s not just you,” she says. “It’s not about you always. It’s about so many other people, and you feel responsible. If there is an attack on you, it’s still a concern. But if there is an attack on someone else because of you, that's something so torturous that you can never live with yourself.”

What she did not publish in the newspaper, though, Sirmed began to post on Twitter, and that’s when things really got bad.

A Unique Classroom Experience

Jarred Riel ’24 (CLAS) is a double major in human rights and human development and family sciences, and he didn’t know anything about Scholars at Risk when he signed up for the “Approaches to Human Rights Advocacy” seminar in the spring semester of 2021 – an HRI course offering designed around collaboration with the network in which students engaged to take actual real-world action working on behalf of imprisoned and persecuted scholars.

The seminar is another component of how UConn has integrated the goals and mission of Scholars at Risk into the experiences available to the growing number of students interested in human rights education and advocacy.

“What really drew me to it was that it wasn’t lecture-based,” Riel says. “It wasn’t material heavy. It was a class where we could get hands-on experience with human rights advocacy.”

The seminar was designed by Sandra Sirota, an assistant professor-in-residence in human rights and experiential global learning with the Human Rights Institute, who had already been teaching a human rights advocacy course at UConn. But Scholars at Risk offered an opportunity for students to put advocacy skills to work in a truly transformative way.

“Having a transformative experience is really important for learners to be able to take something with them long-term, and that’s hard to get if they don’t have the opportunity to apply what they are learning,” Sirota says. “So, with human rights education, I feel that having that element of taking what you’ve learned and doing something that actually is meaningful to you is so important, and it can make the difference between learning advocacy skills and feeling like you have agency, and you have a voice, and you can create change in all parts of your life.”

Through the seminar, which was conducted in an online format, the students learned about ways they could engage in effective advocacy even while working and learning from home. They also learned about a number of scholars imprisoned around the globe, and chose to focus their advocacy efforts on two scholars in Bahrain – Abdul Jalil Al Singace and Khalil Al-Halwachi – and one scholar in the United Arab Emirates, Nasser bin Ghaith.

“They start by researching the country, the human rights issues in the country, the human rights issues related to that scholar, and then the actual case itself,” explains Sirota. “A lot of the scholars, unfortunately, not only are they wrongfully imprisoned, they face severe health issues that they don’t get treatment for. They face torture, some face the death penalty or life in prison. The students do that research, and then they decide what advocacy strategies they want to take on. I help them to think about those different advocacy strategies, what would be effective and what they could accomplish within the semester.”

“None of us had really heard about these scholars in Bahrain, so that’s why we chose to represent them in our projects,” says Emma Harvison ’24 (CLAS), who is studying human rights and political science. “We did as much research as we could using Google, and we actually had the opportunity to communicate with a scholar’s daughter, which was really cool. She told us a lot about her father, and we learned about how they were engineers, and how they were both in human rights organizations in Bahrain, and they were always passionate about promoting human rights in their country, which is something a lot of us as human rights students are also very passionate about.”

Joining other universities across the nation and the world, students began to immediately apply the knowledge and skills they gained through the course to advocate for the rights of the incarcerated scholars.

“I think a lot of us initially were kind of worried about the online format of it, because how much can we do without being able to go out into the world to protest in a big place, like we see a lot in media,” says Harvison. “It kind of shows how much that, as individuals and in small groups, you can really make large differences.”

They developed social media campaigns, contacted and met with federal officials – including staff for Connecticut’s U.S. Sen. Christopher S. Murphy '01 JD and U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro – and wrote letters on behalf of the scholars to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders.

“The advocacy we did to the Special Rapporteur Mary Lawlor – her office actually made a statement following the seminar, in the summer, about the scholar that we had written to her about,” says Riel. “Just seeing that over the summer, it was really rewarding – just to see that some of the work we were putting in was actually getting somewhere was something that was really rewarding.”

The Bahraini scholar Al-Halwachi was released from prison in February after more than seven years of incarceration.

Harvison said the seminar experience helped her build a community of like-minded students who care about human rights and advocacy while also helping develop skills for the future.

“I hope to go to law school one day, and I know that advocacy will always be something that I’m very passionate about,” says Harvison, “and it shows just the little things that I can do in my everyday life that could make big differences and changes.”

Sirota plans to offer the advocacy seminar again this fall, but this time it will be in a two-semester format. Fall 2022 will focus on advocacy skills and strategies, and then Spring 2023 will engage the students in collaborative hands-on work with SAR.

“For me, these are scholars who are doing work in the same profession as I am, and so it has a very personal connection for me,” says Sirota, who hopes the two-semester format will offer more time for students to engage in their advocacy work. “I’m so pleased that UConn is involved with this organization and that I have an opportunity to teach this seminar.”

Not Completely Safe

In October 2019, Marvi Sirmed did finally leave Pakistan – she came to the United States for a fellowship with the National Endowment for Democracy, or NED, and during that time, she began writing a book about South Asian governments and the struggle for freedom of expression.

Since 2001, the Reagan-Fascell Democracy Fellows Program has enabled some of the world’s leading democracy advocates – including journalists, human rights defenders, lawyers, scholars, artists, and others – to pursue independent projects at NED’s International Forum for Democratic Studies. During their time in residence, fellows conduct research and writing, consider strategies and best practices for advancing democratic change, and build solidarity within a global network of democracy advocates.

“Each year, the National Endowment for Democracy awards fellowships to individuals whose scholarship, courageous journalism, and heroic human rights activism have made them targets of persecution in their home countries,” says Zerxes Spencer, director of fellowships at NED. “We recognized Marvi as one such deserving ‘democrat at risk,’ warranting special attention and extended fellowship support, as she recommitted herself to her life’s work from afar. The fellowship period that Marvi spent at NED offered her the space, time, resources, and peace of mind she needed to take stock of her circumstances, gain skills, and plan for the next phase in her professional life.”

But even though she was on the other side of the world, Sirmed’s activism was still making waves at home in Pakistan.

“Last month, I sent a tweet — intended as a commentary on Pakistan’s problem of political abductions — that sparked a violent backlash of gender-based slurs, slut-shaming, and death threats,” Sirmed wrote in an opinion article for the Washington Post in September 2020. “By the next day, #ArrestMarviSirmed_295C became the top trending Twitter hashtag in my country, with countless people suggesting my extrajudicial murder.”

Section 295-C of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws make it a criminal offense to make derogatory comments about the Holy Prophet. Use of the controversial law has increased in recent years, with those accused often subject to threats, harassment, attacks, and vigilantism.

Complaints of blasphemy were filed against Sirmed in multiple parts of Pakistan. Threats to kill, rape, and arrest her escalated dramatically, provoking alerts from international human rights organizations concerned for her safety.

“There was suddenly a fatwa on my head,” she says, “and my family suggested I shouldn't go back.”

Given the escalation in threats against her in Pakistan, Sirmed was strongly advised to remain abroad for a period of time, while things settled down back home. Instead, Sirmed and colleagues at NED looked for opportunities to keep her in the U.S., and found Scholars at Risk.

“With the resurgence of authoritarianism worldwide, the demand for emergency fellowships—for rest and respite, research and writing, outreach and engagement in democratic struggles from afar—continues to outpace supply,” says Spencer. “In light of this grim reality and in recognition of the myriad mutual benefits of a university affiliation, we are eager to engage with colleagues at academic institutions to help make the case for universities as potential host institutions for democracy advocates at risk.”

Sirmed began corresponding with UConn in August 2020, and became affiliated with the University through SAR in January 2021.

In addition to teaching, she is continuing to work on her book while on fellowship with the Human Rights Institute, and while she is able to sleep without fear of being harmed in the night, she says that attacks on Pakistani activists outside of Pakistan – with the government accused of orchestrating those attacks – still leave her feeling unsafe, even in the U.S.

“There was a Guardian story last year about how the Pakistani military establishment has ordered assassinations of the Pakistani dissidents who are in the Western world,” she says, “so, there was a panic. It surged throughout the Pakistani activists who are in different parts of the world.”

Warnings issued in February of this year to Pakistani exiles living in the United Kingdom only further highlight the international threats to activists like Sirmed.

“I have not received any threats here, but all of these things, they keep me wondering,” she says. “It’s not completely safe, but safe in the sense that we trust the law enforcement here, at least more than we do in Pakistan. In Pakistan, we can’t trust the police ever. Even if we are friends with some of their official senior officials, and even if they assure us that they will help us, we are sure that they will never be able to help us, in any way possible.”

Learning that Lives with You

After taking the SAR advocacy seminar, Jarred Riel also signed up for another new human rights course, this one co-taught by Sirmed and Libal that focused on human rights journalism, offered in the Fall 2021 semester.

“It was Marvi who drew me to that course,” Riel says. “I read her story, and it was just so captivating, what she had been through and all the accomplishments she had, but also what she was facing in Pakistan. That she would be teaching this course – I thought it would be something that, honestly, I wasn’t ever going to get an opportunity again to have this type of experience with a professor.”

The goal of the course, Libal explains, was to lay out the emergent area of human rights journalism while also teaching about freedom expression and the importance of protecting journalists who are also human rights actors.

“Human rights journalism reflects an explicit commitment to addressing the most pressing moral issues of our time,” says Libal. “It also means that, as a journalist, you aim to honor and value the voices of those who are experiencing human rights violations, or whose human rights aren’t fully realized. We wanted to have the students understand the core principles of defending human rights as a practicing journalist, which is what has been central to Marvi’s life.”

The course featured guest speakers that included not only other UConn faculty – human rights filmmakers Oscar Guerra and Catherine Masud, and photographer and National Geographic contributor Scott Wallace – but also Sirmed’s colleagues and fellow journalists still working in Pakistan, including the journalist Absar Alam, who himself survived an assassination attempt in 2021.

But it was Sirmed herself, and the openness she brought to the classroom, that had the most impact on the students who took the course.

“It was hard to process that not only was her work interrupted by her government, but that they were actively attacking her, that she was unsafe, and that they were publicly disparaging her to the point that her relationship with her friends, family, and colleagues was fractured. Realizing that this has been such a holistic attack on her life and how horrific the things are that she’s facing – I think that’s so different than reading headlines or hearing whispers of censorship,” says Eliza Russell ’22 (CLAS), a political science major and human rights minor who plans to attend law school after graduation.

“It was invaluable to understand her experiences first-hand and recognize the position she is in today,” Russell says. “It was one of those things that I immediately had to bring up in conversation with people outside the class. It was something that lingered in my mind throughout the semester, not just during class time. I was compelled to share and discuss with other people because I just couldn’t believe the reality of what was going on in her life and in her colleagues’ lives.”

“She told us the details of her story and how she was exposed to government pressures and the government would threaten her, how they tried to imprison her,” says Riel. “It was a different experience than just to hear on the news of journalists abroad facing violence. To actually hear my professor talk about how that violence has affected her personally and how it had changed her life and how she had to leave her home, that was very different than anything I'd ever heard before.”

Though Russell says she doesn’t see herself ever becoming a journalist, her experience in the course changed how she views the work of journalists around the world and opened her eyes as to how she can be a part of a greater movement of supporting journalists and holding governments accountable.

“It is the type of learning that impacts you for a long time, that lives with you,” says Russell. “Those types of stories change your understanding of the world. It’s discouraging, on one end, to understand what her reality is, but it was hugely inspiring to know that this kind of citizen journalism is alive and well, that it’s spreading, and that it’s sounding the alarm on human rights abuses.”

The interaction of SAR scholars with UConn students – through coursework and teaching but also through other opportunities, like independent studies or through engaging the Learning Communities – is not just a way to give students hands-on and transformative learning and advocacy opportunities, Libal notes.

Getting the scholars engaged with students is also enormously regenerative and supportive for the scholars themselves.

“Co-teaching with Marvi was a rewarding experience for me. We learned from each other and from the students,” says Libal. “We often talked about how teaching the course affirmed Marvi’s sense of purpose and that her ideas were being taken seriously by young people in the United States who weren’t familiar with her background and her work. To see them engage her in an authentic and thoughtful way deeply impressed me as well. I’m not sure if the students in class were fully aware of their impact – their engagement inspired us both.”

Sirmed says she hopes that one day she might return to Pakistan, because it’s where she feels she’s needed most.

“But my family is more concerned about my life,” she says. “My husband and my daughter, especially, she says that it’s better if you keep working instead of just trying to work on some story and get killed.”

And so, Sirmed is still writing – publishing regular commentary and columns on political and security concerns in the English-language Pakistani press – and advocating and speaking out about human rights abuses in Pakistan and other South Asian countries. She’s also still tweeting and curating a regular newsletter that she shares on Twitter called Counter Terrorism Pakistan.

But she’s also filled with new energy, she says, after the experience of teaching at UConn for the first time.

“The satisfaction that this work carries, it’s unmatchable,” Sirmed says. “I mean, you are influencing young minds in such a way that can actually change their professional lives – their lives, actually – they will be able to then think in a different way when they hear about the experiences of other people in other countries, about how these journalists are working, and about what is at stake in terms of the person and their life in order to bring those stories to the world.”

She continues, “Even if they do not decide to work in the developing world, if they decide to work here in the USA, I think they will be able to value the freedoms available to them more than they do. Because you don’t value something, you take things for granted, if you are not aware of what it would be like to live without those freedoms.”

For more information about educational and advocacy experiences and opportunities available through UConn’s Human Rights Institute, please visit humanrights.uconn.edu.