Caleb Blanchard ’22 (CLAS) knows firsthand how seriously some young students take science.

When he attended Mansfield Middle School, Blanchard was one of dozens to try out for a spot on the school’s science bowl team, or at least secure a place on its secondary Team 2 or Team 3. He says the competition was fierce and those who were added to the roster would practice almost daily in preparation for the regional contest.

“If you see the trophy section of some middle schools, every kid wants to have one of their trophies in there,” he says. “This is no different.”

But not every student is involved in an activity that’s traditionally associated with competition, yet they’re just as eager to bring their school pride.

“This is very serious for a lot of middle schoolers,” Cat Odendahl ’22 (ENG) says of the Southern New England Middle School Science Bowl. “Coaches train their students before the competition. We’ve had to chase down coaches to get their student rosters because they’re still hosting tryouts or still trying to figure out which students are the best.”

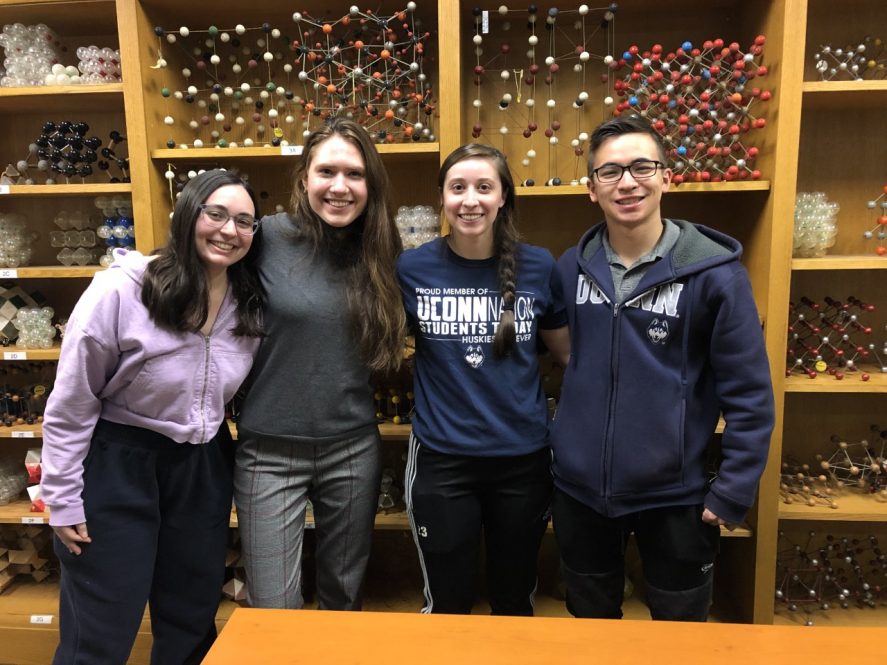

Even though Blanchard is many years from his days as a student participant, he still takes the Middle School Science Bowl seriously – as does Odendahl, Marissa Airoldi ’22 (CLAS), and Viktoria Sinani ’22 (CLAS, CAHNR), who round out the four senior-most members of the Middle School Science Bowl Student Leadership Team at UConn.

The Southern New England Middle School Science Bowl, which is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy but run through UConn at the regional level, accepts up to 32 teams from Connecticut and Rhode Island for a day-long, head-to-head competition to see which area adolescents deserve a place in the national event.

Before it went virtual in the pandemic, the science bowl brought hundreds of competitors, coaches, volunteers, and parents to campus, says Odendahl, who’s been involved since her freshman year. It’s an opportunity to watch the next generation of STEM students compete and to show off what UConn has to offer during the competition’s downtime.

The Engineering Ambassadors, the Chemistry Club, the local chapter of the Society of Women Engineers, and other organizations usually set up tables during in-person competition years to wow the young students with things like elephant toothpaste, a foaming mix of hydrogen peroxide, dish soap, and yeast, Odendahl says.

“It’s science, it’s engineering, it’s technology, it’s mathematics, that’s what life is and it’s only getting more complex and more advanced in all the different fields,” Airoldi, a biology major from Tolland, says. “If you have a good understanding of one area you can see how everything relates. Being knowledgeable in STEM is important because it’s a confidence builder. If someone feels they aren’t musically or athletically gifted, maybe this is their thing. Maybe the science bowl is for them, and they can go out and excel.”

Airoldi got involved only this year after hearing about it from Odendahl, a chemical engineering major from Trumbull. The event was held virtually Feb. 26 and earned Team 1 from West Woods Upper Elementary School in Farmington a spot in the national semifinal competition on May 7.

The questions get progressively harder as teams proceed through the event, says Blanchard, a biological sciences major from Mansfield. They may start with something simple like, “What is the powerhouse of the cell?” and eventually go into algebra 2 or AP biology by the final rounds – topics usually reserved for high school and beyond.

“Viktoria and I were in the room when they were doing those rounds,” Airoldi says, “and I was thinking I wouldn’t have known that when I was in middle school.”

Odendahl says one of this year’s sample questions asked about the difference in topology between the East and West coasts. It was a multiple-choice question, but the roughly 10- to 14-year-olds needed to think about the definition of the word topology, then about the geography of east versus west, and then about similarities and differences.

“One of the schools, they did this as a class,” says Sinani, a molecular and cell biology and animal science major from Branford who’s been involved for three years. “That is very intense.”

But now after STEM-centric college classes, she sees how the different fields work together: “All of the subjects interconnect. I understand how that works because I learned this in chemistry class. This makes sense because I learned this in this class, and this makes sense because I learned this in this class. Combining it together, at least for me personally, it’s a very euphoric feeling.”

Seven UConn undergrads rounded out the Student Leadership Team alongside the four seniors, working in various capacities to organize volunteers, coordinate coaches, maintain records, handle logistics, and ensure financing and fundraising. They also served as scorekeepers, moderators, and made sure the day, even via Zoom rooms, ran smoothly.

But all the effort was worth it: “We do this ultimately for the kids, for the middle schoolers to have a great experience,” says Blanchard, who’s been involved in organizing all four years.

“Curiosity is probably one of the most important things you can have in your childhood,” Odendahl says. “You’re giving these kids super hard questions and you’re letting them explore the topics that are given to them. That goes back to why STEM is important. Everyone will have crazy ideas and who knows what’s right or wrong. Who knows who’s going to come up with a cure for cancer? It could be a middle schooler right now. You can’t say no to them. They need to explore and see what can happen.”

Airoldi agrees, “It’s almost like a bottomless pit. You learn about something in middle school, and then you learn a little bit more about it in high school, and then in college you learn what seems like everything about it. Exposing young people to a certain topic in middle school and then more and more as they get older, I think that keeps them engaged.”

After all, Sinani reiterates, “Going into STEM, you just kind of learn about the whole world and understand how it all works. And if you find something interesting, you can delve deeper into that.”