For today’s thinkers and doers and the generations that come after, Ruth Braunstein has one question: What does America mean to you?

“The public is always thinking about it whether they know it or not,” she says. “Our assumptions about what it means to be American are embedded in so many of our conversations about public policy. Who deserves access to public institutions and resources, whether we should allow certain religious groups to display their religious symbols in public, do you need to be a taxpayer to be a good American? There are so many ways this plays out in the background of our policy debates.”

Most of the time, though, the general public doesn’t get to answer, says Braunstein, an associate professor of sociology who runs UConn’s Meanings of Democracy Lab. Politicians and elected officials, institutional and corporate top brass typically make decisions that end up defining “America” for those who comprise it – like what holidays are observed on the public school calendar.

Last fall, she sought to change that with the help of political science professor and President Emeritus Susan Herbst, who came across a 1937 contest in Harper’s Magazine soliciting written submissions that attempted to define America in that time.

“We can’t see all the answers submitted in the 1930s, but from what we can tell, they are the standard ones: that democracy is fragile, citizens are not always informed and are open to manipulation, and there are indeed problematic leaders with poor intentions,” Herbst says. “Like many intellectuals in the 1930s, there was tremendous concern that the United States could see the rise of authoritarian movements right here on our own soil.

“We were watching the rise of Adolph Hitler and other dictatorial leaders and many American journalists thought the topic of our own future was a vital one,” she continues. “While our contemporary situation is different, we do have the same fears as we watch demagoguery at home and abroad. The parallels to the 1930s, and shared concerns, are stunning, in fact.”

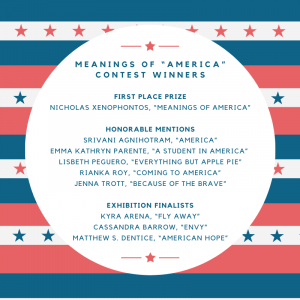

Rianka Roy, a graduate student in sociology who received an honorable mention and one of five $100 prizes in the Democracy Lab’s “Meanings of ‘America’ Project,” offered the acrostic poem “Coming to America” that describes her immigration to America and questions whether the “alien” designation on her passport – despite legal status – will thwart a sense of belonging.

“Millions of immigrants have come and settled in this country. They love the country, work for it, and cherish the opportunities they find here,” she says of the poem. “But often their views are ignored. They are stereotyped as outsiders who threaten national security and jeopardize the economy. On the one hand, we want to embrace our adopted home, on the other hand, we are made to feel unwelcome.”

Braunstein says she received between 50 and 100 entries for $1,000 in prize money funded by UConn’s Humanities Institute and the Department of Sociology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. There was one first-place winner, five honorable mentions, and three finalists. Submissions came from students throughout UConn who were told to go beyond the usual patriotic rhetoric in their submissions, be creative in their ways of looking at the country, and ultimately “rally enthusiasm” as the Harper’s contest also called for.

“There were a lot of students expressing concern about a more exclusionary vision of the country and they were very critical of that,” Braunstein says. “There were many who talked about racial injustice and the movements that have emerged to resist racial injustice, including Black Lives Matter. I was impressed with the thoughtfulness of the responses – some very critical, some holding this tension between critique and patriotism and hope.”

Sandy Barrow ’19 (CLAS) ’22 MPH submitted her painting “Envy,” a silhouette portrait of Audrey Hepburn done on a background of old United States maps, to illustrate the American drive to be better and do more, oftentimes at the cost of lost identities from going the wrong way.

“Look out for her because she’s sly,” Barrow says of the painting done in black acrylic. “Envy and those feelings of competitiveness they aren’t always overt. They’re a little bit throughout the day or a little bit throughout the month or the year. They’re sneaky and they can have bigger impacts on your mental health and wellbeing than you realize. When you formulate your goals and your journey, you’re bombarded with other people’s expectations and oftentimes you’re not able to forge your own path or be happy with the path you chose. When you see her, you get captivated.”

It’s a cycle that’s unique to America, Barrow, who was a contest finalist, says: “We work harder and have longer workweeks and less care for our workers than many other comparable and developed countries.”

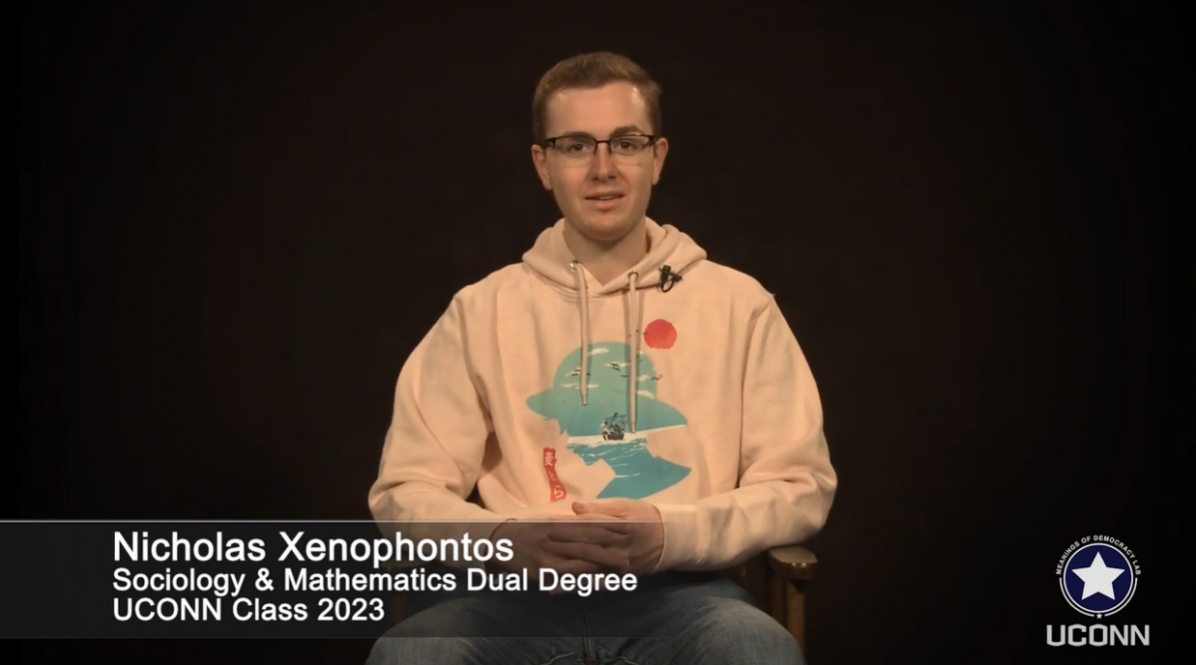

For contest winner Nicholas Xenophontos ’23 (CLAS) the fact that “America” doesn’t have a definition is perhaps its greatest strength. In his essay, “Meanings of America,” he notes the country is free, brave, and just – but that allows landlords the freedom to raise rent, advisors to recommend stifled tears to manifest courage, and siblings to support opposing sides of laws and differing views of good and evil.

“Try any core pillar of American identity and you will find hypocrisy, redundancy, and irony,” Xenophontos says in the essay that won the $500 top prize. “Our entire history is one of betrayal to any of our intrinsic merits, starting with the colonial destruction of the Native society, land, culture.”

Because of this tension, America is meaningless, he says, allowing people to define it for themselves.

“My inspiration came from a deeper cynicism and slight nihilism that permeates the mood of my generation,” he says. “If we don’t discuss the personal meanings we hold to our nations or institutions, then those tainted values that cement themselves in our lives will remain unquestioned. We must talk about what America means to us, for the hope is that our voices lift each other up and we hear each other. After all, talking does us very little good if we don’t open our ears and minds to what is actually being said.”

Braunstein says she wasn’t surprised the contest drew students from majors outside the expected political science, sociology, and public policy realms. In the Democracy Lab, her students come from a range of majors, including philosophy, business, and computer science, and they are “excited by the opportunity to stretch their legs a little bit and think about topics they don’t get to think about as much in their coursework but are personal interests of theirs.”

They’ve helped with the lab’s website design, spread word of the contest, served as contest judges, and promoted the full project on Twitter and Instagram. Staff at UConn’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning videoed the winners talking about their submissions.

Now the students and Braunstein are looking ahead to what’s next – a documentary-style podcast, “The Battle for the American Story.”

Recording of the first episode happened in late April.

“In the podcast, we reflect on where we are exposed to these different versions of the American story, starting in childhood, at church, through rituals, and during holidays,” Braunstein says. “What are the moments when people begin to question some of those ideas they have been exposed to – like the myth that America is a sacred ‘Christian nation’ – and who are the voices today who are critiquing that version or promoting alternate versions of the story? Who is promoting a story of the country as a racially and religiously diverse country that has a flawed past but is working toward the vision of a more perfect union in the future?”

Talking about America’s past is important for its future, as Xenophontos says, and Herbst agrees.

“As a social scientist, you always want to ask ‘So what and who cares?’ when you are studying a phenomenon like American public opinion. I do think it is important to get inside the heads of average citizens, as best we can. If people value democracy, trust each other and the democratic process, they will build a better nation,” she says. “They will work together and make sacrifices for the greater good.”