Two hundred thousand (and counting).

A flowering branch of spicebush native to Connecticut was recently logged as the 200,000th specimen in UConn’s George S. Torrey Herbarium. Since 1898, when the University was known as the Storrs Agricultural College, the herbarium has played a critical role in research and education for generations of students and faculty, and now hosts the world’s largest collection of plants native to the Nutmeg State.

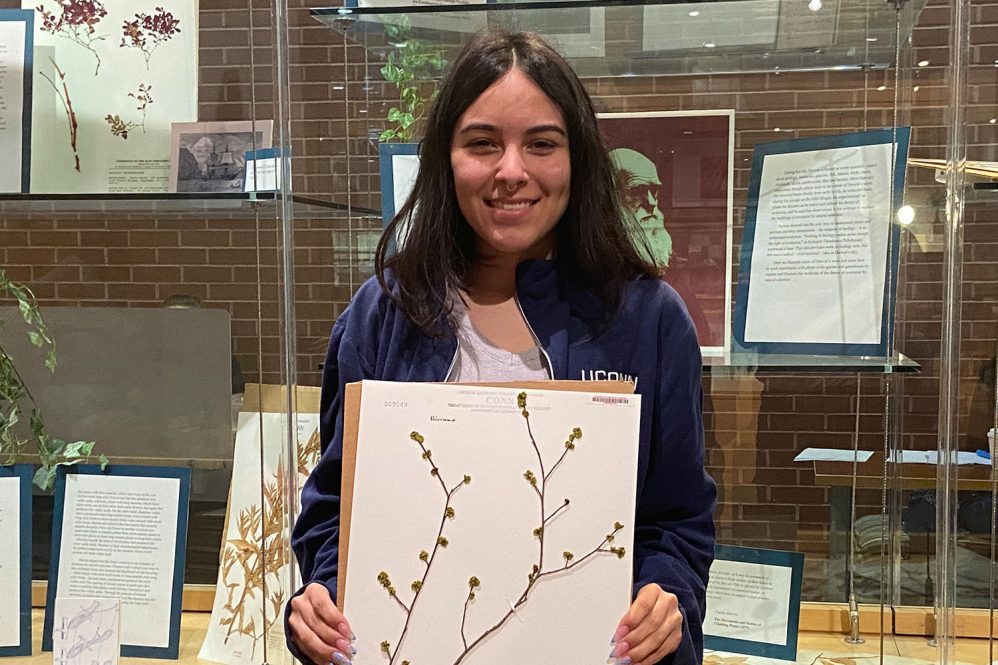

The milestone specimen was collected by independent study student Michelle E. Hernandez ’22 (CLAS). Hernandez’s project documented woody plants in their winter conditions and fills gaps for future researchers because, Herbarium Collection Manager Sarah Taylor says, there is a bias for when plants are collected for several reasons,

“There are almost no collections done in the wintertime,” Taylor says. “The herbaceous parts of the plants are dead, the woody material can be challenging to identify, and conditions to go out in the field might not be great.”

Taylor will be attending the Society for Preservation of Natural History Collections conference and presenting a poster developed with Hernandez that details the story of the herbarium and the milestone specimen.

Taylor says it was important to have a student collect and describe this milestone specimen. It highlights the important role students have in helping to build and digitize the collection while they gain new knowledge from the collection along the way.

Taylor recalls a story that Hernandez told her that illustrates these impacts. Hernandez’s roommate was curious to know why she had a jar of seemingly random sticks in their kitchen, and when Hernandez identified them for the roommate, it was the first time she realized she was gaining knowledge that wasn’t obvious to others.

Collections serve as keepers of natural history – the natural history that we may often overlook but which is nevertheless priceless. In a nutshell, says Interim Director and Curator Bernard Goffinet, the herbarium has the best record for plant occurrences in Connecticut through time. Since 1996, specimens have also been digitized, expanding the collection’s reach to the global community.

More locally, the collections curators also lead tours.

“We have students who come through who oftentimes didn’t know the collections were here,” says Goffinet. “We try to build awareness because we know there are students who will be interested in coming into collections management.”

Taylor adds that interacting with people on the tours are a highlight, since people view the collections from their various points of view.

“We hear new perspectives on collections, which is, as an instructor is extremely interesting to me. I love hearing how the students perceive the collections.”

One common question is about the importance of collections, Goffinet says.

“It engages the students in a discussion about our natural history and allows us to talk about how many species there are on the planet,” Goffinet says. “There is much that remains to be discovered, because a specimen is an endless source of information. There will be new techniques in the future to study the specimens that we don’t know about now. I say the collection is like a library, every individual is a book, except that there is no last page. We keep adding pages to the story. In that sense, you can’t just say, ‘Oh, nobody’s reading this book anymore. I’m just going to throw it out,’ because you don’t know what else may be written or how the story will continue to unfold.”

A recent study emphasizes the way new pages can be added to a specimen’s story, says Goffinet. Scientists found microplastics in the guts of fish collected and preserved half a century ago, showing that microplastics are not a new problem, but rather an ongoing and worsening one.

Collections of specimens also make other studies possible – for instance, the work of UConn researcher David Wagner, who studies insect decline – says Goffinet.

“How do we know this trend is happening? What is the baseline? This is where the collections are so important. If we talk about changes in flowering time, for example, how do we know?”

Details like these can be gleaned from the specimens carefully collected, documented, and preserved. In this sense, every collection is unique and contains irreplaceable specimens.

“You can take a picture, you can take a DNA sample, you can do whatever you want, but you can never replace it because it is the most comprehensive unit that holds all of the data,” says Goffinet.

The collection helps foster collaborative research not only at UConn, but among scholars at other institutions or in other states.

For example, Tammo Reichgelt from the Department of Geosciences is working with students to image specimens in the paleobotany collection to explore past climatic conditions and to analyze the diversity of insects who fed on the leaves. Another researcher in Massachusetts is studying common, native orchids, working to determine their range across southern New England.

“We also send out material to loan to researchers at other institutions. We sent some to the New York Botanic Garden, and Chris Martine ’06 Ph.D, now at Bucknell University, who deposited specimens here in our herbarium and has now sent a postdoc and a grad student to come and take small leaf samples so that they can extract DNA for his research,” says Taylor.

There is a wealth of stories left to tell, especially considering that not every specimen is correctly identified or cataloged yet, says Goffinet.

“There was a study in in PNAS a few years ago that suggested that 50% of the plant species that have yet to be described have already been collected in our herbaria. We just don’t know it. This is because there are backlogs. It’s easy to collect but it takes a lot more time to identify them properly.”

Addressing the backlog has been a priority over the last year or so, says Taylor. One aspect is exploring the contents of a sizable cabinet bequeathed to the collection labeled ‘Eames Duplicates?’. A student determined that hundreds of the specimens were in fact not accounted for in the database. Another source of the backlog is from researchers collecting specimens on research trips but not identifying or cataloging them.

“Again, it’s easy to go out and collect specimens, it’s hard to identify them accurately,” says Taylor.

Goffinet says that on tours, curators emphasize the collections are not simply the outcome of scientists hoarding materials, rather the collections hold data that are for everyone. Tour participants are generally fascinated, and sometimes inspired to join the efforts at managing the collections, says Taylor.

“This is a record of the natural history of the state,” says Goffinet. “It should be treasured because if it is lost, we can’t recover it.”

To learn more about the history of the herbarium or to explore the digital collection or see an image of the milestone specimen, visit the Herbarium website.