When Forrest McClendon started at UConn in the mid-1980s as a computer science and electrical engineering major, the Fine Arts Complex was just another building to walk by on junk food runs to Store 24 in what is now Downtown Storrs.

But as he passed by in those early days away from home, McClendon ’89 (SFA) says the music practice rooms that looked out onto Route 195 caught his attention.

“Eventually, I slipped in to play the piano – it was my refuge from the computer lab,” he says. “As a non-major, I eventually pursued private voice lessons, which required participation in choir. That’s how I came to the music department and the School of Fine Arts. There was a place for me even though it wasn’t my chosen field of study at the time.”

Today, the Tony Award-nominated McClendon is among two dozen major entertainers listed on the UConn Foundation website who’ve walked the halls of the complex in the southeastern part of campus over the last 60 years.

Their careers and those of the thousands who graduated alongside them with majors and minors in the departments of Art and Art History, Digital Media & Design, Dramatic Arts, and Music are success stories, each a testament to the strength of the school that was created in March 1961 and saw its first dean appointed on May 16, 1962, and seated on Aug. 1 that year.

“When I think about the anniversary of the school, my focus is as much on the next 60 years as it is on the prior 60 years,” Interim Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs and previous SFA Dean Anne D’Alleva says. “It’s a moment when we not only can celebrate our past and the many achievements of our faculty, staff, students, and alumni, but also look to the future.”

But first, the last two years

There’s no doubt the pandemic devastated the arts world, separating performers and artists who oftentimes need to be face-to-face, eye-to-eye to do their work well. Professional and student work has been curtailed or modified, producers and instructors had their plans stymied, curators and collaborators were stopped in their tracks.

“It is the single-largest challenge I have experienced in my 30-plus-year career in the performing arts and the single-largest challenge I have encountered as a full-time educator in the last decade,” dramatic arts department head Megan Monaghan Rivas says.

The Connecticut Repertory Theatre, of which Monaghan Rivas also serves as artistic director, had only one show, “The 39 Steps,” open on time and make a full run in 2021-22, she says. The other five shows had to adapt to remote rehearsals and quarantines, not to mention winter weather and power outages. “Food for the Gods,” scheduled for the first two weeks of December, was hit hardest by the virus.

Challenges mounted in the music department as well.

Professor and department head Eric Rice says he couldn’t stop thinking about the virus outbreak in Washington state in March 2020 when a choir rehearsal turned into a super-spreader event, resulting in 52 infections and two deaths from one infected participant.

“The memory of that hung over me as I was thinking about how to run our programs,” Rice says, noting that singing and instrument playing have been among some of the easiest ways to transmit the virus – and that’s the heart of what his students and faculty do.

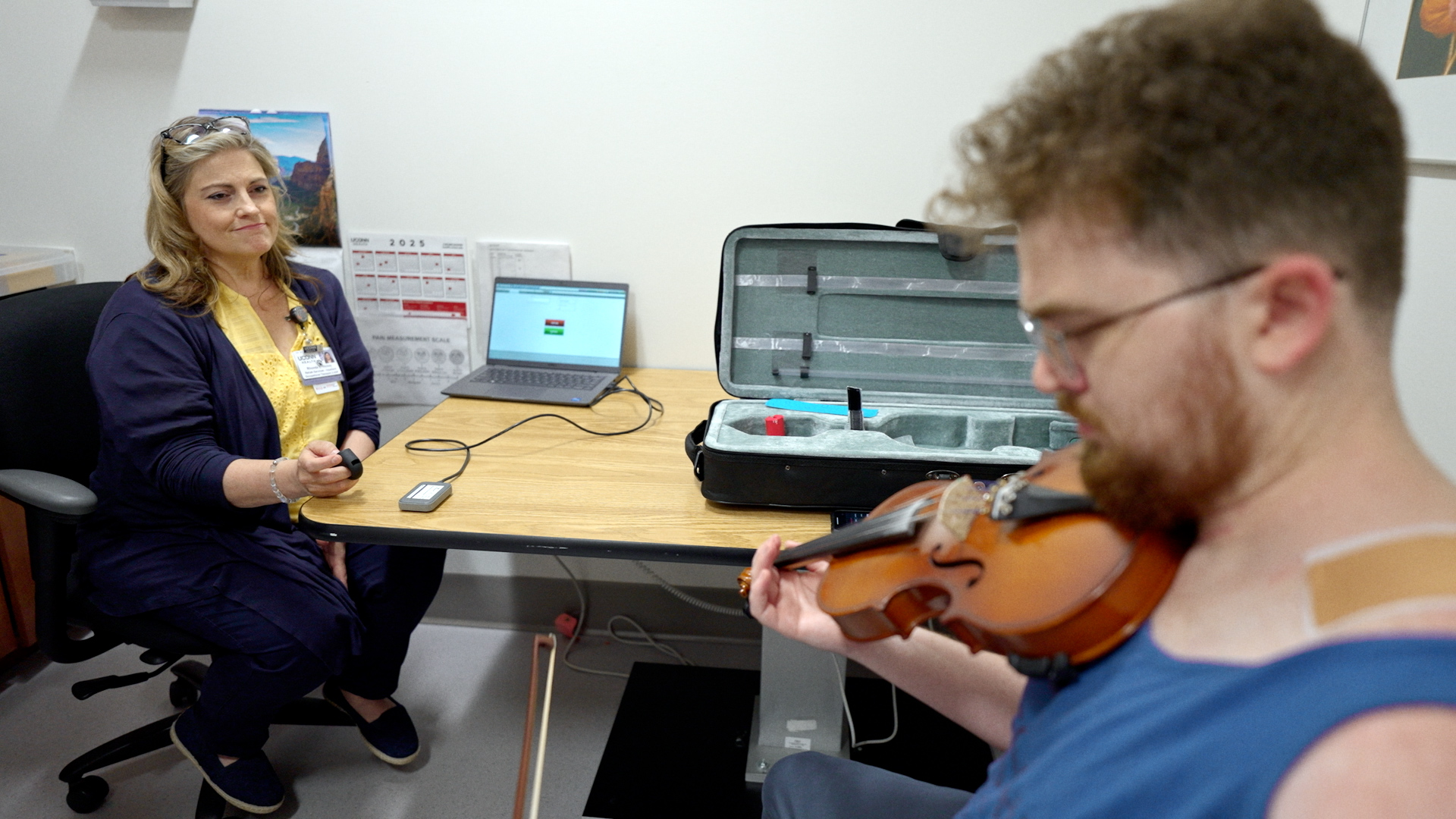

With instrument bell covers and face masks, musicians in 2021-22 tiptoed into the traditions of student recitals and ensemble performances. The UConn Herald Trumpeters announced commencement. The Voices for Freedom gospel choir celebrated its 50th anniversary.

“We want people not to lose sight of what a live performance actually is and how very different the energy of a live performance is versus consuming something via a digital means,” Rice says. “As a music historian and a music conductor, one of the things I’m always having to remind students is that before the age of recorded sound, if you wanted to hear music in your home you had to make it yourself.

“It’s ironic,” he continues, “because that means the skill level of your average person was probably a little bit higher on instruments and singing than it is today. On the other hand, people today are bombarded with music in a way they weren’t even 100 years ago. That change has meant people are confronted with much less live performance than they used to be and if the pandemic has taught us anything, a live performance in communion with each other is an incredibly valuable experience that’s hard to duplicate.”

Art consumption evolving

Monaghan Rivas says that before the pandemic, audiences were starting to consume art in a different way, seeking out interactive and immersive events that would give them personalized experiences. The pandemic thwarted that when it forced social distancing and isolation. Two years later, drawing people back into theaters, museums, galleries, and recital halls is the goal; figuring ways to provide individualized attention is next.

“During the pandemic, so many people reached for books, music, film, all forms of artistic expression to keep loneliness at bay, to keep their fear under control, to bring strength and peace at a moment when they craved it. But also, so many people turned to artistic expression to reconnect with themselves,” Monaghan Rivas says. “As soon as you give people uninterrupted time, often they start making art of some kind – photography, quilt making, sourdough. Folks were not only consuming art early in the pandemic, they were making art. Our audience has been transformed. What that could mean for us as artists is the thing we get to discover over the next several years.”

Constance DeVereaux, director of the MFA Arts Leadership and Cultural Management program in the dramatic arts department, says that no matter how the arts struggled in the pandemic and continue to recover, they’ve survived worse.

“People go to the arts when things are not going well in the world and when things are going well. We find solace in the arts,” she says. “What the pandemic has done is made us rethink a lot of things. That kind of pause has probably been good not only for arts organizations but also for audiences to rethink about what it is they want. Artists seem to be able to figure out how to adapt. Who knows what the arts are going to be like in 20 or 30 years?”

UConn’s arts leadership program, in short, trains students on how to manage arts organizations, DeVereaux says, so predicting what those organizations will look like and do over the duration of a person’s career is a challenge. The key is to be nimble.

She’s been doing some of that at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, where just prior to the pandemic University officials sought a way to have an arts presence in the capital city near the Hartford campus. The result is a newly constructed suite of offices on the second floor of the museum for graduate classes.

“People might look at an arts school and think, ‘Why do we need that?’,” DeVereaux says. “The presence of an arts school in higher education – and one that thrives as this one does in a state university – is so important to what that university is. It’s saying we appreciate the whole human being and everything that human beings are.”

Collaboration, collaboration, collaboration

Judith Thorpe, MFA Studio Art program director, photography professor, and former head of the art and art history department, says one of her MFA students recently took a drama class in body performance and movement so they could get a better sense of how arms, legs, and torsos shift through space. They’re using that imagery in their sculptural work.

This kind of interdisciplinary work benefits artists who draw inspiration and expertise from many non-traditional sources, Thorpe says. Oftentimes, UConn art students look to other subject areas – creative writing, physics, and biology – for inspiration, not to mention round their education.

“There are a lot of great art schools especially in this Northeast region, but they don’t have the strength of the Research 1 status,” Thorpe says of UConn’s designation as an R1 university. “There’s an ability at UConn to have a broad range of experiences in students’ education both at the graduate and undergraduate levels to develop their work based on an intense center view, which the art program provides, and a broader view provided by the full University.”

This connection to other subject areas fosters continued collaboration – take, for instance, the Krenicki Arts and Engineering Institute, created in 2019 as a place for engineering students to learn skills geared toward the arts.

“The Krenicki Arts and Engineering Institute is a unique home for students who have passion for both the arts and engineering,” Institute Co-Director Edward Weingart says. “Many are not aware that it is possible to pursue both in an academic environment and professionally until they arrive in Storrs. Our programs blend pedagogical styles from both disciplines in order to foster students who will be more prepared to enter the job market whether they decide to continue to work in the intersection of arts and engineering or if they embrace more traditional engineering careers.”

Another place to see collaboration at work is in Digital Media & Design, SFA’s newest department created in 2013 thanks to the efforts of the schools of Fine Arts, Business, and Engineering.

“Our program is one of the most collaborative on campus in that we work with everybody,” Michael Vertefeuille, associate department head and one of the original department members, says. “We’re in the School of Fine Arts, but we’re really a central hub for the rest of the University. Many people come to us. We’re working with the College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources; School of Engineering; School of Medicine; School of Nursing. We’ve done research projects with the School of Business. There are very few schools and areas that we haven’t collaborated with and that’s because of what we do.”

With classes that range from interactive media design to 3-D animation, film production to digital culture, department head Heather Elliott-Famularo says DMD students learn technical skills that allow them to work in any field and almost any profession.

“As much as we emphasize technical skills and aesthetics, we also talk about stories,” she says. “Interactive stories, time-based stories, stories through still images, stories through audio: Storytelling is the focus of what we do whether those stories are nonfiction or scripted. And we share those stories with diverse audiences for entertainment, business, and even science communication. That’s what situates us best in the School of Fine Arts. Our faculty members not only consider themselves artists or designers, but also storytellers.”

As often as DMD collaborates with the rest of the University, sometimes it stays closer to home.

In 2018, DMD and music students collaborated on “Synesthesia,” a music and visual performance that illustrated for an average audience the colors and visual changes synesthetes see when they hear sound. The following year, they worked on Connecticut Repertory Theatre’s production of “If We Were Birds,” developing custom animations projected as the background scenery. Now, dramatic arts students seeking the experience of video work are teaming with film production students looking to use professional actors in their projects.

“What’s really exciting is how collaborative and interdisciplinary the arts are, and not just at UConn but broadly across the art world,” D’Alleva says. “The arts are engaging important social issues like racial justice and climate change.”

Accolades and the long view

“I’m very proud of our collaboration with the Human Rights Institute,” D’Alleva adds. “We created a research cluster last year around the arts, social justice, and human rights, and DMD established the Human Rights Film & Digital Media initiative in Fall 2020. This is groundbreaking, inspiring work.”

In these achievements, D’Alleva gives credit to the people who make the school and its collaborations success stories.

Its faculty: “We have a stellar faculty with Emmy Awards, Grammy Awards, Guggenheim Fellowships, Fulbright Fellowships, Mellon Foundation grants, and Luce Foundation grants. It’s inspiring that, as accomplished and internationally renowned as our faculty are, they are in our studios and classrooms everyday teaching our students.”

Its staff: “The staff of the School of Fine Arts is fabulous. It’s an incredibly dedicated, collaborative staff implementing the vision for the school and moving us forward at every step.”

Its students: “Our students are academically talented, highly creative, ambitious, and dynamic. To see the wonderful things they do here as students and then out in the world, honestly, it’s just a joy to see the impact they’re having.”

Its alumni: “We have such accomplished and loyal alumni, and they complete the circle. They return to SFA as mentors, teachers, and guest artists, helping us educate the next generation of students.”

And together, they’re marking a diamond anniversary while looking ahead to what comes next at 70 or 80 years and beyond.

“I see the future of the arts as collaborative and dynamic, inclusive and global, dedicated to human expression and to social change, and it’s wonderful to say that UConn is a place where all of that already happens naturally,” D’Alleva says. “Forging collaborations, driving change, breaking down silos and boundaries, that’s UConn. And that’s where the arts are going.”