Two hundred eighty years ago, nine generations in the past, more than four decades before the signing of the U.S. Constitution – and Sarah Grosvenor had the ability to choose.

In towns like Pomfret, that eventually would comprise the new country, women had a name for what the teen did. Sometime in May 1742 she started “taking the trade,” or an abortifacient to induce a miscarriage. The herbs, berries, and plants in the recipe were plentiful in New England, oftentimes cultivated by women for women.

When that didn’t work after months of trying, around this time of year, sometime in early August, a doctor performed a manual abortion. She miscarried a few days later and because medical care wasn’t near the modern standards of today, developed an infection, probably sepsis, and died on Sept. 14.

Despite the tragic outcome, and putting aside that she hesitated along the way, conflicted by her choices, Sarah Grosvenor’s actions in the early days of her pregnancy weren’t outright illegal leading up to the signing of the U.S. Constitution and in the immediate years that followed.

Doing what was needed to regulate a woman’s menses, even if that meant inducing a miscarriage before the stage of quickening, was more common than what today’s audience might believe. Early term abortion in the founding days of the country was a morality issue, not a criminal one.

“The recent U.S. Supreme Court decision on abortion elides the fact that in English common law, going back to the medieval period and up through the early 19th century, attempts to miscarry or abort before quickening were not illegal. To repeat, these were not criminalized,” says Cornelia H. Dayton, UConn history professor and author of the 1991 article “Taking the Trade: Abortion and Gender Relations in an Eighteenth Century New England Village,” which traces the story of Sarah Grosvenor.

“Until the early 19th century, there were so few prosecutions of people providing abortions that it’s very hard to understand how concerned people were about the practice,” she says. “They did not seem terribly concerned that this was a widespread societal issue. General public opinion seemed quite tolerant of young women and their decisions.”

Simply put, if Sarah Grosvenor had lived, Dayton says, charges would not have been brought.

Children wrestle with family control

Life in the mid-to-late 1700s was different than today.

“With the exception of a relatively small number of port cities, society was heavily rural,” retired UConn history professor Christopher Clark says. “Nearly 90 percent of the population of the United States lived in the countryside after the Revolution, and many of them lived from the land in one way or another.”

Slavery was legal, albeit stronger in the South than in the North, and the Industrial Revolution was just beginning to take root, Clark says, which meant mechanized machinery hadn’t made its way to most towns and villages in rural America, so working with one’s hands was the way to get things done.

It was a time of survival, nation building, and establishment.

“Most people had to work long hours to survive or earn their livings, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t concerned about things like courtship, marriage, pregnancy, and child-raising,” he says. “One of the interesting things about the late 18th century, particularly in New England, is that there is evidence premarital sex was common. People didn’t write about this, and we can’t interview them, but one way we can measure the occurrence rate is to look at birth records and compare them with marriage records.”

Doing that shows a quarter to a third of first-born children were to couples who had been married fewer than nine months, he notes, proof of premarital sex. One might blame a lack of restraint on the part of these young adults caught up in a hormonal rush, but that’s likely not the whole explanation.

“Families tended to have greater control over the marriage of their children – particularly if they were females. And one way you could get around your parents prohibiting you from marrying a person was to become pregnant with a child by them, in which case the couple would have to marry,” Clark says. “Is this a lack of restraint among early American teens or too much restraint among their early American parents?”

Historians are inclined to believe the latter.

Clark says that literary authors by the late 1700s and early 1800s, like Jane Austen, started to question the purpose of courtship and marriage – should these partnerships be for romantic intent or functional arrangements.

“Particularly with the rise of the Romantic novel in England and other parts of Europe,” Clark says, “there was a focus on the wishes of young people as distinct from the wishes of their parents and the notion that marriage need not necessarily be a dynastic question. Jane Austen, in all her novels, deals with this question. Do you marry the person with money, or do you marry the person you love?”

Not in dire trouble

Sarah Grosvenor and Amasa Sessions conceived their child sometime in late February or March 1742 – whether out of love, lack of inhibition, or another reason.

“Most young people in this society at the time were pregnant before they got married so there was a lot of premarital sex happening,” Dayton explains. “Most of them married, and even if the couple did not agree to marry and the man went off, the young woman was not usually in dire trouble. She was not rejected by her parents. If she came from a farming, middle-class family, she often kept the child. She apologized before her church and was fined in court. In addition, my research shows these women went on to marry someone else in a few years and often her new husband informally adopted the child.”

She continues, “it’s a mystery why these two young, white people from prominent families in Pomfret went to such great lengths to hide the pregnancy from their families – even from Sarah’s own father and stepmother – and then end it.”

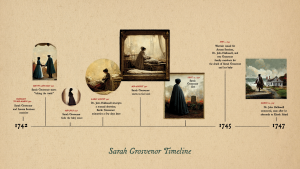

A dedicated history department website that details Dayton’s research and the timeline of events indicates Sarah Grosvenor learned she was pregnant in mid-to-late May – when the fetus was between 10 and 13 weeks’ gestation and still a few weeks before she would have felt its first movements. She told Amasa Sessions, and almost immediately started taking the trade at his urging.

“Ethnologists and others who are experts on Native cultures of New England think there’s pretty strong evidence that Indigenous women had methods to control births,” Dayton says. “Indigenous women were quite good at spacing children more widely apart than settler women. We’ve often wondered to what extent Indigenous women passed on knowledge to settler women.”

Nancy Shoemaker, UConn history professor and author of the 1999 book “American Indian Population Recovery in the Twentieth Century,” says that indeed Native Americans used birth control, but mostly after conception.

“The most common form of limiting births available to Indian women was abortion achieved with the use of plant abortifacients or pressure applied to the woman’s abdomen,” she writes, noting that in 1826 the Cherokee Council outlawed abortion among the tribe and the Senecas also prohibited it in the early 1800s.

But that came much later than Sarah Grosvenor, by eight decades, and coincides with other similar societal changes in the United States around that time.

The secret among Native American women, whether by design, necessity, or accident, was the length of time they breastfed their children, Shoemaker says. Breastfeeding generally equates to lower fertility because of inhibited ovulation, which would naturally space births – and if done only by accident offer the illusion of family planning.

Still, this wasn’t lost on some settler women.

“Even though we talk about the pill and how amazing it was in the 1950s, family planning and birth control were very normalized prior to that among European settlers,” says visiting UConn faculty member Elisabeth Davis, who this fall is slated to teach “Colonial America: Native Americans, Slaves, and Settlers, 1492 to 1760.”

“Breastfeeding was considered an easy way of family planning,” she says. “Women breastfed their children not only until they were a year old like we do today, but until they were toddlers. It was a very natural way for people such as Anne Hutchinson to pace how often they had children.”

Anne Hutchinson, a Puritan who lived from 1591 to 1643, a century before Sarah Grosvenor, gave birth regularly every 18 months over the course of 25 years, Davis says. Even Thomas Jefferson’s daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, who lived from 1772 to 1836, was successful at spacing her children between two and four years apart.

“That’s not unusual,” Davis explains, “because it gave women an opportunity to raise a child who is more likely to survive during this time of massive childhood mortality.”

Breastfeeding was an easy and natural way to do this – although not always guaranteed and perhaps only for a delayed time. Sometimes, a woman needed to look to other methods, and, Davis says, that wasn’t much further than her own backyard.

“In the 18th century, you have separation of women’s work and men’s work. Women’s work was in the garden, so many women were very skilled herbalists. They used herbs they had available as a form of early abortion, what they called getting their menses started again, as a form of birth control. You learned it from your mother and your mother learned it from her mother,” she says.

Even Benjamin Franklin published a recipe for an abortifacient in the book “The Instructor.” The book contains a section on at-home medical remedies for things such as gout, but there’s also an entry with instructions on how to restart a woman’s monthly cycle using herbs and plants from the garden.

“If your humors are out of sync, you would take an herb and it would cause a miscarriage, or an abortion by our standards today, but back then it was just getting your body regulated,” Davis says.

Clark agrees, “There was not a lot of concern about early stage abortion in this time. The concern was, if there was one, what damage an abortion would do to the woman.”

A medical abortion in 1742

Around the middle of July 1742, six to eight weeks after she started taking the trade, Sarah Grosvenor felt the first flutter of movement, known as quickening and which happens between 16 and 20 weeks’ gestation. She turned ill, and by the end of the month, still sick, was in the care of Dr. John Hallowell.

Amasa Sessions conceded to marry her, according to Sarah Grosvenor’s sister, and promised to publish the banns – only, he reneged, and their intent was never publicized. Instead, in early August, Amasa Sessions fetched Dr. John Hallowell to attempt a medical abortion.

“We assume this wasn’t common,” Dayton says. “We don’t know how many people attempted to miscarry or abort, and we assume that if they did, they tried nonsurgical methods. We learn more about surgical abortion in the 19th century. There was no germ theory at this time; people didn’t understand that for another 130 years or more. Procedures were done and none of the participants washed their hands before the next one.”

Certainly, this was not a time of sterile conditions, never mind surgical precision.

Dr. John Hallowell, with a past that included an arrest for counterfeiting, was unsuccessful in removing the fetus, not surprising for someone without a medical education. He sent Sarah Grosvenor home to recuperate; after a few days she miscarried in her father’s chamber with her sister by her side. Accounts differ on whether the child was half-term or full-term.

For about a week Sarah Grosvenor rested comfortably, even gaining strength to do light work around the family house, until she again turned ill in the middle of August and lingered about a month until her death.

The story doesn’t stop there. Abortion before quickening was legal at the time, but just before her medical abortion, Sarah Grosvenor had felt movement and as a result of the procedure she did die.

Three years later in November 1745, arrest warrants were issued for Dr. John Hallowell, Amasa Sessions, and two female Grosvenor family members for the death of Sarah Grosvenor and her baby. The detailed court depositions that became part of the case are what allowed Dayton to uncover and unravel the story.

“This is the best documented, if not the only, trial we know of from British Colonial America, in which a doctor and other people are prosecuted for an abortion or miscarriage that was performed by inserting an instrument into a young woman,” Dayton, who studies history through court records and legal cases, says. “This was so rare that the county attorney for the king was confused about how to handle the case.”

Charges against the Grosvenor women, brought because they were among only a handful of people who were in the know and who helped their kinswoman throughout that summer, eventually were dropped – Dayton says it’s arguable the court initially held them complicit only to get them to talk.

For Amasa Sessions, who procured the abortifacient and the surgical abortion, the grand jury found the proposed indictment “ignoramus,” meaning they believed there was not enough evidence for the case to move forward. He went on to marry another woman and have 10 children. He’s buried in Pomfret, 25 feet from Sarah Grosvenor’s grave.

Dr. John Hallowell was the only one held accountable, found guilty under English common law of the “highhanded” misdemeanor of endeavoring to destroy Sarah Grosvenor’s health and “the fruit of her womb.”

“Keep in mind, that’s only a misdemeanor,” Dayton stresses. “It’s notable that’s not a felony and is one notch down from being a felony. English legal treatises classified abortion after quickening – but not before quickening – as criminally punishable, but not necessarily at the level of the most serious crimes.”

And, thus, he wasn’t ordered to the most severe punishment.

Dr. John Hallowell was to be held in custody for several weeks before stepping in the gallows for two hours with a rope around his neck. He was to be whipped 29 times on a bare back and returned to prison for an uncertain length of time. But before the sentence was carried out, he escaped to Rhode Island.

Aside from a personal appeal that was denied, there’s no further record of him in Connecticut.

Early look at malpractice

“The fact that the medical provider is the one who’s successfully indicted fits with what happens over the next 150 years when the courts are looking at the doctors and not prosecuting the young woman who either agrees to or seeks to have an abortion,” Dayton says. “These prosecutions really arose out of concern for what we might call malpractice, the mother’s vulnerability and death. It’s when a young woman died from a procedure that prosecutors brought a case.”

With the turn of the century, Dayton says, abortion providers were not targeted unless something happened to the woman: “The focus is on abortions that lead to serious harm to young women. They’re not, as far as we can figure out, focusing on the fetus. There’s no ideological discourse about protecting life from conception. It’s concern about the young mother’s health.”

That’s not to say the life of a full-term, or nearly full-term, baby wasn’t protected.

“Often what we see is what would be considered late-term abortions that are classified as infanticide,”

Davis says. “There was this obsession with infanticide particularly after the American Revolution when the prevailing idea was to populate this new nation.”

Dayton says society at the time knew the women who were brought to trial for infanticide were likely unmarried and likely servants in a house who needed to work, so they concealed the pregnancy and birth.

“When I read these cases, the cause of the child’s death seems very uncertain. Was the child stillborn? Did the abortifacients force a miscarriage at late term? Or did the baby die at its mother’s hand? We don’t know, and neither did the juries who were quite sympathetic to these women. Even though they were cast as child murderers, there were a lot of acquittals.”

In the 18th century, without the big-box stores of today to stock up on onesies and other essentials, pregnant women would handcraft linens for their expected arrivals, Dayton says. If such a linen was entered as evidence in an infanticide case, the woman was almost always acquitted.

“It’s as if the public was looking for reasons to give these women the benefit of the doubt and understood the enormous pressure they were under,” she says. “This evidence from infanticide cases suggests society was understanding of the pressures young women endured when they unexpectedly became pregnant.”

Dayton’s current research has expanded to look at the history of mental health, and she notes the same stigmas that exist today didn’t back then. People were sympathetic to those in their circles who developed depression or psychosis; they weren’t frustrated or put off. They were accepting and tolerant of the challenges such a condition brought.

“What’s hard for us to understand is that it didn’t stigmatize the person for life. They really thought that mental health crises came and went, that they were episodic, so they didn’t attach to the person – even though, of course, there were some people who struggled with this chronically.”

Society changes in the 19th century

After the American Revolution, after the signing of the Constitution, after Francis Scott Key wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner” and Abraham Lincoln was born, American society started to change at the turn of the century and into the 1820s.

With each of these events came structure, a society that no longer was making up the rules and instead was living by the rules. The Industrial Revolution took hold, technology changed, and factories became workplaces over fields.

“You see the growth of these massive towns due to immigration from Ireland and Germany,” Davis says. “People aren’t just staying on the coast in Boston or Philadelphia, they’re going inward. Buffalo, New York, becomes a big town, Pittsburgh, anywhere along a river. And that scares people.”

Communication got better with the invention of early telegraphs, and better printing presses allowed news to travel much faster and farther than before.

“We make such a big deal that self-publishing is unique to today when, really, in the 1820s anyone could write a pamphlet and publish it,” Davis says. “So that means people could get their ideas out to a massive audience much quicker. That gave rise to religious reformers who wrote about these ideas of men and women, and more people read these ideas.”

The country transitioned into what’s known as Victorian America – and attitudes around sex changed.

“It’s after the American Revolution, in the 1820s, that we see a religious revival for 30 to 40 years when people become more religious,” Davis says. “This is when we see a shift from ‘we’re having sex and it’s fun’ to ‘we can’t talk about this, sex is for reproductive purposes only.’”

Clark says family size by the mid-19th century became smaller than what it was in the 18th century, maybe the economics of getting married or raising a child played a part. But the average age of a new bride rose, which reduced the number of child-bearing years she had in wedlock.

“During this time there was a shift in ideas about children: how many children to have, what you would do with them. Do you see children as beings to be raised, nurtured, and educated? Or do you see children as labor for your family,” he says. “Over the generations these things all add up to a big change.”

Among them was the establishment of professionalized medicine.

Doctors in the late 19th century – including a group of Boston physicians in the 1870s and 1880s – started pushing for abortion laws, Dayton says. These Boston doctors were concerned that white, married women were seeking abortions to have more leisure time. Indeed, they were having smaller families with fewer children – fewer than their immigrant counterparts.

“Doctors maintained that married women seeking abortions were to blame for a change in the make-up of the population, which is a racist, nativist argument,” Dayton says. “Another mystery to us is when stronger abortion laws were enacted, there was no recorded legislative debate. The provisions were often tacked on as revisions to the criminal code. Further, there was no media coverage and no evidence that lobbyists were influencing the direction of the law.”

Clark notes that at this time the medical profession comprised mostly men.

“Obviously, there were male physicians before the 19th century, but a good deal of what we would call medical treatment was in the hands of women, especially in rural areas,” he says of pre-1800. “Particularly the task of caring for newly delivered mothers largely was in the hands of women until the early 19th century when men started to take control.”

‘Abortion is part of our country’s history’

The 39 signers of the Constitution in 1787 were men and, true, they did not include specifics on women’s rights or abortion.

“The United States Constitution doesn’t deal with anything that is practical, other than how government should be established and conducted up to a point. It dictates how the powers of government are limited,” Clark says. “It doesn’t say anything about abortion, but it doesn’t say anything about most things that would concern people’s lives.”

The only time the Constitution involved itself in people’s daily living, he argues, is with the passage of the 18th Amendment, which was ratified in 1919 and prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol. It was repealed with the passage of the 21st Amendment in 1933.

Dayton says that arguing against abortion by pointing to its omission from the Constitution is flawed.

“The Framers of the Constitution and the authors of the 14th Amendment, which guarantees due process and equal protection of the laws, had much more limited notions of rights than we do today,” she says. “It’s a convenient argument, but it’s wrong to impose on 18th century thinkers the expanded constitutional rights that have come about over the nation’s history.”

There’s another argument to be made.

“If you want to say abortion isn’t in the Constitution, neither is the rights of women or people of color or Indigenous persons,” Davis says. “Nevertheless, when we look at what women were talking about, what they were doing when this country was founded, yes, abortion is part of our country’s history. It was seen as very natural versus this taboo that develops in the late 1800s.”