Museums, libraries, archives, and research collections all rely on carefully controlled climates to protect the priceless objects they house. What happens when things go awry? On a typical quiet morning in April of 2021, a terrible set of circumstances in UConn’s Biodiversity Research Collection led to every collection manager’s biggest fear, but thanks to an all-around quick response, everything turned out better than expected.

A Waterfall in the Dry Room

Routine tests were being done on fire safety systems on the morning of April 7th, says Collections Manager Erin Kuprewicz. Since many samples in the collections are preserved in very flammable ethanol, the collections have unique fire suppression systems which are tested regularly by external contractors.

Somehow, the system was accidentally discharged, and though the sprinklers did not engage, tiny pinholes resulting from corrosion in the pipes resulted in a disastrous deluge to rain down onto the mammal bone collection.

“There was basically a waterfall. It was truly the worst scenario for anyone working in collections.”

Fortunately, Collection Manager Katrina Menard, was there to see the events unfold and began calling the rest of the team right away. It was all hands-on deck says Kuprewicz, and everyone rushed to the scene. The water was shut off but after about 10 minutes of leaking, the damage was significant.

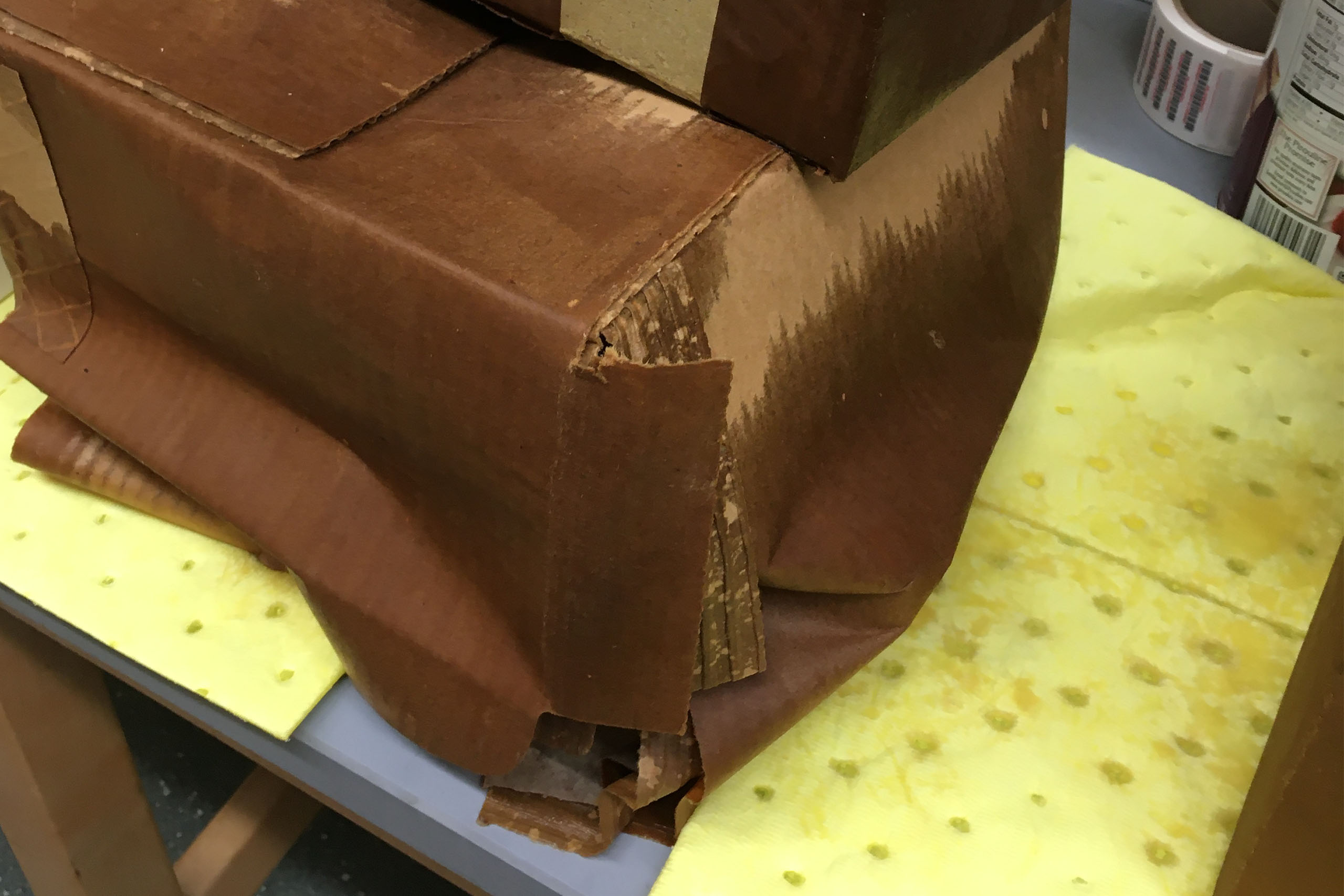

“Initially, there were around one or two inches of water on the floor and the leak was right above the mammal skeleton collection that was stored in cardboard boxes.”

The (Careful) Rush to Action

In all, 612 mammal skeleton specimens needed quick attention and the team rushed the wet boxes out of the space and into a nearby classroom. Kuprewicz says not all the boxes were purpose-built archival boxes. In fact, many of them were fish stick boxes from the 1970s and were beginning to disintegrate.

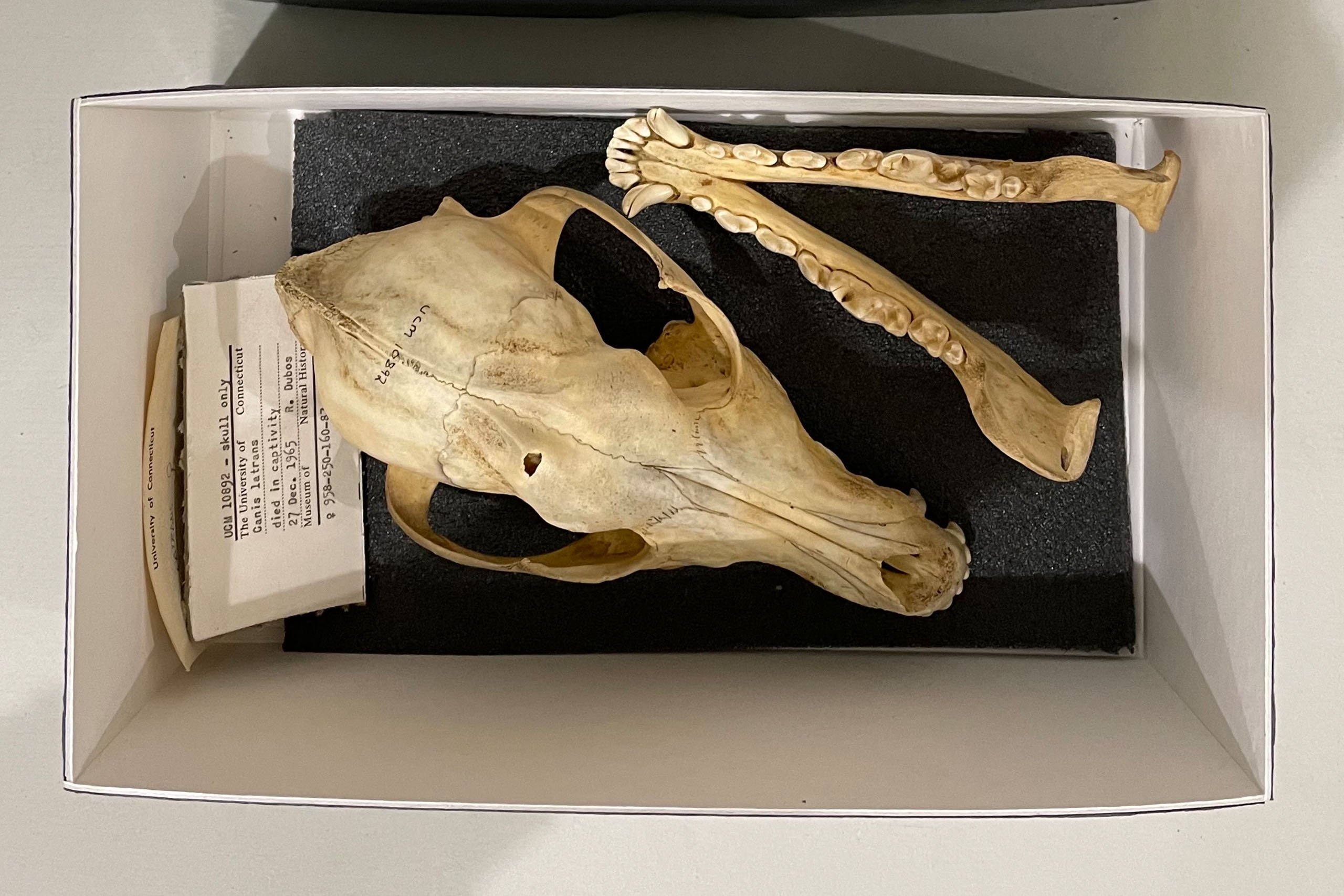

The biggest concern with moving is keeping each specimen’s information intact and together. If something were misplaced or put into a different box, that really compromises the data says Kuprewicz. Despite the chaos, they were successful in keeping everything intact and together.

“Surprisingly, we managed to do it. I don't know how but we were able to get everything out that day. At that point, it was so bad. We spread everything out on all the tables and did a rapid inventory.”

Kuprewicz assessed the extent of the damage and made a list of everything that would be needed to safely rehouse the specimens. Kuprewicz says with help from facilities, they were able to get dehumidifiers and industrial fans in to dry the collections room. Within about 48 hours, the specimens were also totally dry.

“One silver lining is the specimens were bone. If they’d been a skin or taxidermy or anything other than bone, this would have been so much worse. Even though the boxes were destroyed, for the most part, they did their part and protected the bones, very few of the bones inside the boxes got soaking wet.”

Making the Most of a Bad Situation

Kuprewicz says they realized that this disaster was a good opportunity to make improvements and thanks to a quick response from the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Office, they were able to secure the necessary funds,

“We thought if we are going to take everything out of these old fish stick boxes, what is the best we can do? A big problem for many collections they are usually operating on a shoestring budget, but our administration was great. I put together a budget and I was able to quickly hire two students to help. They both had taken the Natural History Collections introduction course (EEB 5500) and knew how to deal with bones and collections.”

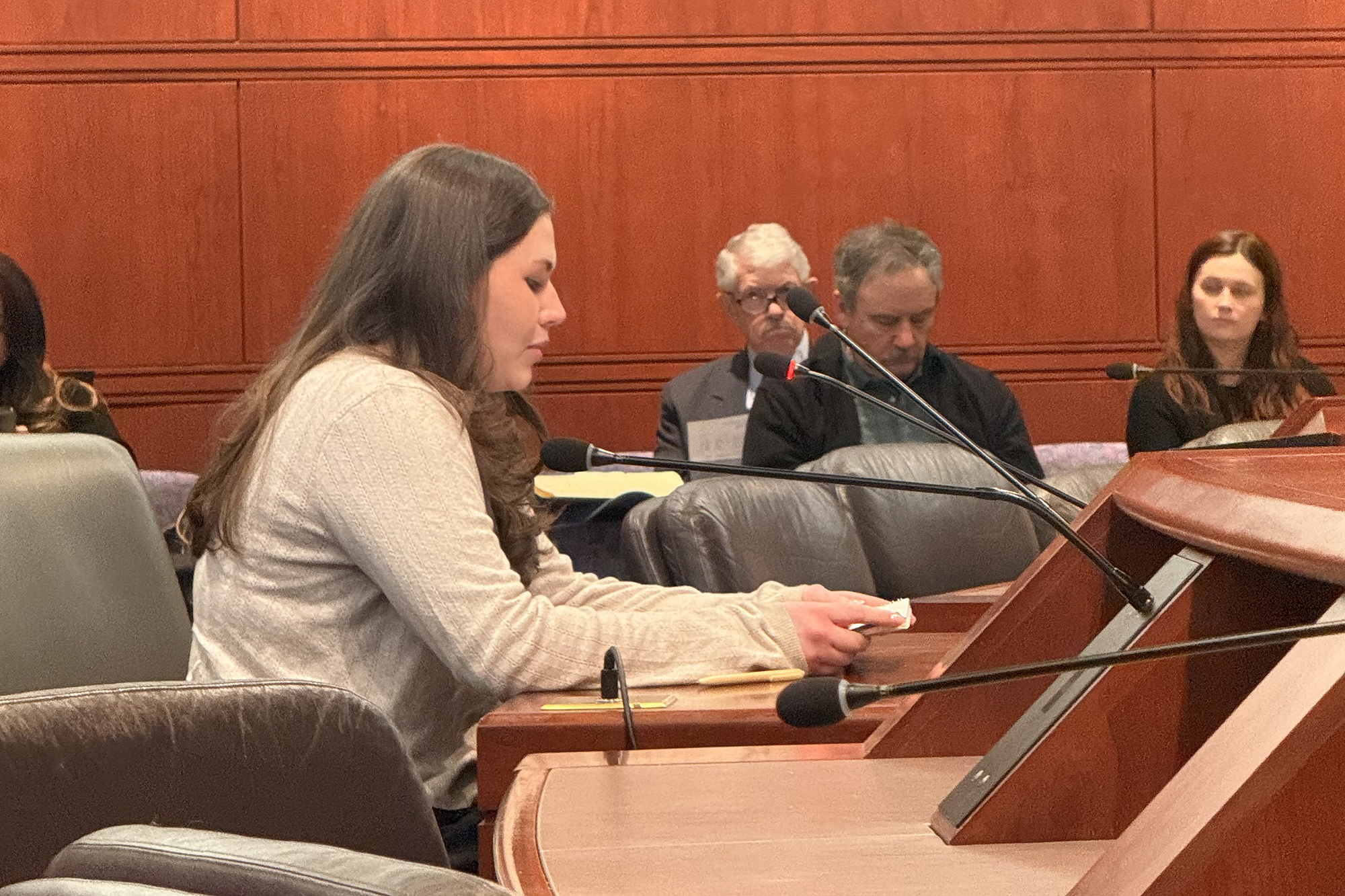

Over the course of the summer, Kuprewicz, and the students, Frank Muzio ‘25 (PhD) and Greyson Nackid ’22 (CLAS) worked to make the improvements. They put together the protocol used the rescue the specimens and mitigate the flood damage. After finding it difficult to find other resources and information to guide them, Kuprewicz decided it would be helpful for others to have access to this protocol, so she decided to write a paper detailing the incident and protocol. It is published in the journal Collection Forum.

“I was able to use list servers for the Natural History Collections community (especially NHCOLL-L) and got a lot of help which was awesome. I thought this paper would be a great resource for others.”

The Frozen Final Stretch

Nearing the end of the summer and quickly approaching move-in, one final and important step had to happen quickly. Besides water and fire, other scourges of collections and archives include pests, like insects, bacteria, or mold, that can quickly ruin specimens. After the flood mitigation measures, all the specimens needed to go through a period of freezing to kill any potential pests before they re-entered the collection’s carefully controlled environment. This required renting a freezer trailer which was parked outside of the Biology and Physics Building.

“We had this giant trailer freezer that was potentially hindering movement on the walkways in front of the building. We worked in batches where we kept the specimens at a cold temperature for three weeks at around minus 15 Celsius, to kill anything that could potentially hitchhike into the collection. While we wanted to kill everything, we also needed to be careful to not break the bones because freezing and thawing can cause damage.”

After the long freeze, the trailer’s temperature was gradually raised to acclimate the specimens and avoid condensation forming. Finally, everything could safely return to the collections facility.

Now a year later, Kuprewicz reflects that throughout the whole ordeal, the team kept reminding themselves that it could have been much worse, and in many ways, they were very lucky.

“We took it as an opportunity to make everything better. The bones got upgraded into nice boxes, they got cleaned, and new labels. Those 612 specimens look great.”

They also double-checked the database and corrected errors, so it was also a chance to improve the data shared with the world.

“We couldn't have done it without the funding support of the dean's office. It was a long process but we're in a lot better shape now.”

The support showed the collections managers how valued the collections are to the UConn community, and that support is vital, says Kuprewicz.

“Every specimen is priceless. You can never replicate that snapshot in time when each specimen was collected. You don't know how we could use the information in the future, either. If we think about the advances in genetics or molecular technology, they were unheard of 20 years ago. We have no idea in the future what technology will be able to go back and reference these specimens.”