Headlines and reports detailing insect decline are becoming more frequent and urgent, however, we have yet to take meaningful action to slow or stop it on a worldwide scale. Mitigating climate change must be at the top of our to-do list.

A paper out today in Ecological Monographs by an international team of nearly 70 scientists, including UConn Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology researchers David Wagner and Carlos Garcia-Robledo details the troubling trends, but also offers actionable solutions the world can take to avoid losing these key players in ecosystems worldwide.

The publication is just in time for the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference COP 27 being held from November 6 to 18 in Cairo, Egypt.

Gradual changes plus extremes

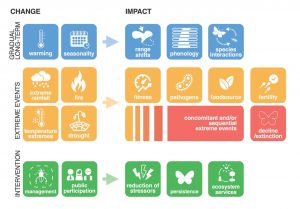

The paper provides a compelling overview of the role of climate change and climatic extremes in driving insect decline.

“Climate change aggravates other human-mediated environmental problems including habitat loss and

fragmentation, various forms of pollution, overharvesting and invasive species,” says lead author Jeffrey Harvey from the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW) and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

“Insects play critical roles in so many ecosystems, but we are rapidly losing at least part of them,” Harvey explains.

This seems especially the case in temperate regions. The authors emphasize that both longer-term events and short-term extremes are harming insects in several ways.

“The gradual increase in global surface temperature impacts insects in their physiology, behaviours, phenology, distribution and species interactions.” Harvey adds: “But also, more and longer lasting extreme events leave their traces.” Hot and cold spells, fires, droughts, floods.

“Most insect diversity is in the tropics,” Garcia-Robledo adds, “but we know so little about the consequences of warming on insects and their interactions.”

Piling up

Evidence of the effects is piling up, and it’s all presented in this review. For instance, fruit flies, butterflies, and flour beetles can survive heat waves, but males or females become sterilized and thus unable to reproduce — a sort of ‘living dead’.

Bumblebees prove particularly sensitive to heat, and climate change is now considered the main factor in the decline of some North American species.

“Cold-blooded insects are among the groups of organisms most seriously affected by climate change because their body temperature and metabolism are strongly linked with the temperature of the surrounding air,” says Harvey.

One major concern with insect decline in a warming world is that the plants on which insects depend for food and shelter are similarly affected by climate change. As plants are affected, insect numbers in turn will dwindle, and this, in turn, will cascade its way up the food chain. Evidence is increasing that insect declines may be behind the decline in bird populations.

“Ongoing experiments in tropical mountains in Costa Rica show that if temperatures increase beyond 2 °C, some insect populations will become extinct,” says García-Robledo: “It is also very concerning that these populations lack the genetic variation required to rapidly adapt to novel temperatures.”

Supporting the global economy

Insects play roles in pollination, pest control, nutrient cycling, and decomposition of wastes.

Harvey quotes the late renowned ant ecologist Edward O. Wilson, who long argued that insects were the little things that run the world.

Insects also represent the overwhelming bulk of biodiversity and while performing vitally important services that sustain human civilization, their activities amount to staggering amounts of money (trillions of dollars) annually to the global economy.

Declines in insects could have enormous consequences for agriculture, the economy, and even the stability of some nations, says Wagner.

“Over time, insects must adjust their seasonal life cycles and distributions as it warms,” says Harvey. “However, their ability to do this is hindered by other human-caused threats like habitat destruction and fragmentation and pesticides.”

Furthermore, short-term heatwaves and droughts can drastically harm insect populations and the plants and wildlife that depend on them

What to do

Importantly, the scientists not only describe the problems but also discuss a range of solutions and management strategies to help to buffer insects against climate warming. Wagner urges that must find ways to make agriculture more nature friendly, while at the same time finding ways to feed more people, and do so in more socially just ways. Individuals can help by landscaping with native plants, providing areas where insects can shelter to ride out climate extremes (e.g., by reducing the sizes of our lawns), and by reducing the use of pesticides and other chemicals.

“At the larger scale, we need to address climate change. Rewilding programs also need to consider micro-scale ecosystems which focus on the conservation of small animals like insects,” says Harvey

“Insects are tough little critters and we should be relieved that there is still room to correct our mistakes,” says Harvey.

But time is running out. We need to enact policies to stabilize the global climate. In the meantime, at both government and individual levels, we can all pitch in and make urban and rural landscapes more ‘insect friendly.’

Wagner cautions that we are staring at the planet’s sixth major extinction, — we can and must do better, embrace an ethic of stewardship over our planet, and take the necessary steps to build a sustainable and just future for humanity and nature.