Just before Molly James ’23 Ph.D. visited South Korea in August, the country had experienced significant flooding, the worst in 80 years, during a monsoon season that caused the Han River to overflow and wash out many areas of Seoul.

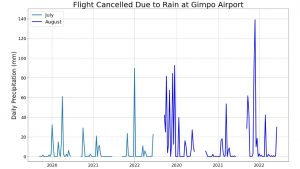

It’s a storm that on a graph comparing the country’s daily precipitation in July and August of the last three years shoots a spike significantly higher than other daily records. And for James, it’s a storm that gave pause, as she tried to figure out how to account for it in her latest project – translating scientific data into song.

“This project doesn’t necessarily focus on climate change, but it’s hard not to think about it when you see the graph about rain,” James says. “When you analyze a change over time, it’s obvious there are fluctuations that have happened because of climate change. You can see it in the data, and you can hear it in the music.”

James is a self-described numbers person, who studied physics as an undergraduate and now as a marine sciences graduate student at UConn Avery Point looks at the hydrodynamics of the salt marsh system and how tides affect creeks and adjacent grasses.

She loves math.

“But in my college orchestra, the entire trombone section was physicists,” she notes. “I played tuba alongside them, and now I play trombone in the Southeastern Connecticut Community Orchestra. Music is all patterning; it’s math. The scales work the left side, the logic side, of your brain.”

James met Hea Youn “Sophy” Chung, a Julliard School-trained pianist from South Korea, about five years ago and reconnected during the pandemic to practice conversational speaking in each other’s native languages. Chung was impressed with James’ work as an oceanographer and suggested they partner on a different project, one that would combine their strengths.

They decided to use publicly available data from the Korean Meteorological Administration – the equivalent of the National Weather Service or the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in the U.S. – and translate into musical notes various data points, James says, whether temperature or wind speed or another measure.

Chung then tapped the right side, the creative side, of her brain to build chords and melodies to turn each song into a piece that’s pleasant to the ear. A planning grant from the Arts Council Korea funded the full project and allowed James to travel to South Korea for 2½ weeks last summer, a trip during which the pair recorded some meteorological data of their own, including temperatures and humidity levels.

“This project is meant to make people feel more connected to the environment, make people feel more connected to nature,” James says. “Looking at graphs is not something that’s intuitive for most people, but music is a way that you can communicate something, even if it’s very abstract.”

Find a Baseline and Assign It a Note

James says one of the best sounding of the five songs is about precipitation, “Flight Cancelled Due to Rain at Gimpo Airport,” the song that took note of that historic monsoon rain.

In writing it, James says, she and Chung assigned the piano’s low D to the rain measurement of zero, times when there was no precipitation. Each added millimeter corresponded to a piano key, with the notes moving up the register to use as many of the instrument’s 88 keys as possible – 30 millimeters of rain equates to the key that’s 30 away from D1.

But the historic August storm recorded at one point 140 millimeters of rain, well off the keyboard.

“Consequently, in the music you hear this huge jump from the lowest register to the highest register of the piano,” James explains, adding that Chung set a quick tempo for the 48-second song to mimic the patter of raindrops. “We looked at the various graphs and found a baseline number that we could assign a note. All the other notes are in reference to that.”

“Flight Cancelled” was straightforward to write, James says, while the other songs layered in a bit more of the data. For “One Week in Incheon,” a sonification of the air temperature, the two used hourly temperatures on a graph from December 2021, found the weekly average, and assigned that data point middle C to establish a melody line.

“Overlaid on that we had chords that were made from the daily maximum, daily average, and daily minimum temperatures. The result is you feel this progression in the longer term over a week, but also the movement throughout the day of what the temperature is,” James says. “To me it sounds a little somber, but to Sophy it doesn’t.”

In adding a layer of complexity to “Wind and Waves from the East Sea,” Chung brought in the second half of her two-person musical group, 2SO, to perform it as a four-hands concerto – one person playing the wave data on one side of the keyboard, the other playing the wind data on the other end, James says.

“Scientifically and physically, it makes sense because the wind is what’s causing the waves so there’s a direct connection and we thought that would be an interesting combination to do,” James says. “That one, I think, was the hardest because there were a lot of moving parts to arrange.”

Chung performed the songs, along with selections from composers Anton Arensky and Claude Debussy, during a concert carrying the same name as the project, Harmony of Nature, in Seoul on Nov. 13. It’s the first of what the two hope will be a continued collaboration.

“Going forward, we want to explore more with different key signatures or how we decide the starting reference point. These statistical interpretations lent themselves well to it,” James says.

With historical and future data in endless supply, James says there are myriad directions the pair can go as they continue to create. They plan to apply for additional funding from the Arts Council Korea and bring in more collaborators, including another scientist and more instrumentation, to develop longer and more complex compositions, James says. A focus on oceanographic phenomena also is likely.

James says that in addition to oceanography research, she’s professionally passionate about science communication, and this project – even without words – does just that.

“The focus of this work and what we do in the future is about getting people to feel more connected to their natural environment,” James says. “We want people who hear these songs and say to themselves, ‘Oh, I’ve been there’ or ‘My aunt lives there,’ and have them connect to the music and to the data.”

Listen to the professional recordings on Apple Music, Spotify, or Amazon Music.