Like the company they created together, Leila Daneshmandi ’20 Ph.D., ’21 MA and Armin Tahmasbi Rad ’19 Ph.D., ’20 MA got their starts at UConn.

During their PhDs, Daneshmandi focused on tissue regeneration, while Rad specialized in nanotechnology and cancer medicine. The stars aligned for the creation of their biotech startup when they both enrolled in a class on technology, innovation, and entrepreneurship led by Profs. Hadi Bozorgmanesh and David Noble.

“That’s where we came together and we learned about the process of user-driven innovation and entrepreneurship,” says Daneshmandi. The pair began to speculate about what they could accomplish by combining their respective expertise.

Four years later, their startup, Encapsulate, is on a mission to change the future of precision cancer treatment.

Growing (and treating) tumors on a chip

Before the launch of Encapsulate, Rad had been working with Prof. Mu-Ping Nieh in the Institute of Materials Science to create a nanoscale universal drug delivery system for fighting cancer. The resulting product could “encapsulate” any type of cancer drug for targeted delivery into tumors. During its development process, Rad worked with cutting-edge ex vivo research techniques, which allow scientists to test the efficacy of different treatments on patient cell samples that are cultured outside the body.

Drug developers have had a few decades to appreciate ex vivo research since the technique’s development, around the close of the last century. But clinicians and patients typically don’t have access to the same technology for their own use. Together, Daneshmandi and Rad began envisioning a way to bridge that gap: an automated system that would allow cancer patients to receive personalized, precision medicine based on tests from their own tumor biopsies.

Currently, oncologists monitor patients’ response to a given treatment, determining after a certain period whether a therapy had a positive, negative, or negligible effect on the patient’s cancer. Often the wait means a loss of valuable time, with the care team ending up back at square one if the treatment isn’t effective.

Rad, Daneshmandi, and their co-founder, Reza Amin ’18 Ph.D., ’20 MA, wanted to create a technology that would allow clinicians to test multiple drugs at once and quickly determine the best course of action for each patient.

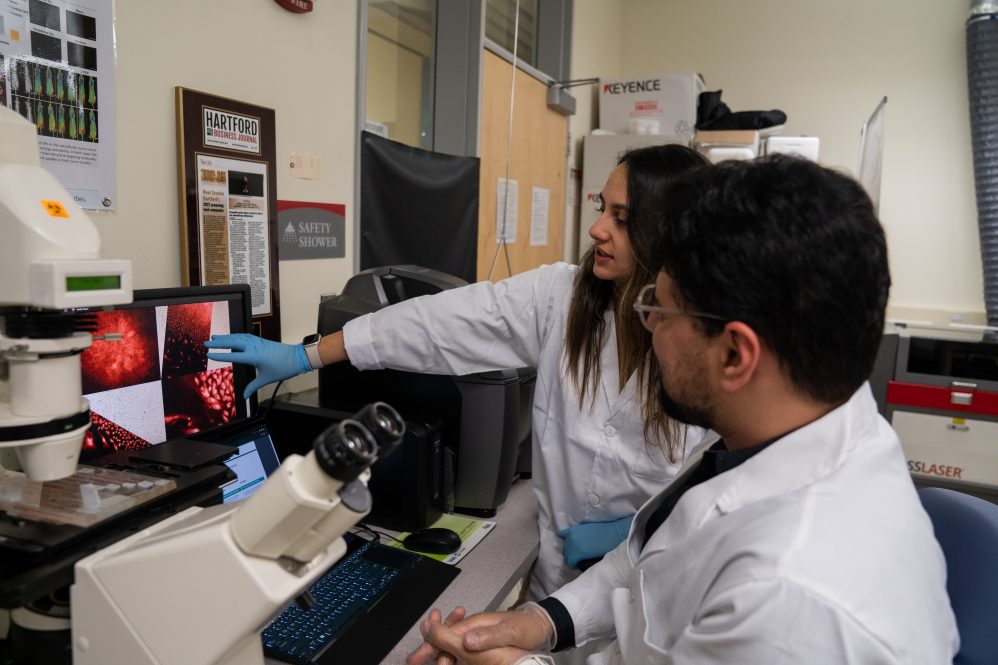

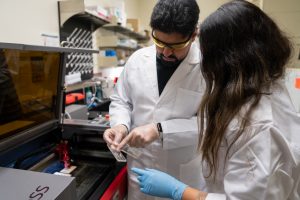

In short, they wanted to develop nCapsule, the startup’s signature product. This biochip is “able to very quickly, very precisely mimic the body,” according to Rad. It can grow bona fide microtumors using the cells from patients’ tumors. Encapsulate’s other staple technology, nCapsulizer, processes the biochips and tackles treatment analysis.

“You will find a way to persevere”

Early responses to their idea ran the gamut, from skepticism to enthusiastic collaboration. Daneshmandi describes being kicked out of one office in the early days of their talks with clinicians.

“Someone said, ‘This is never going to work,’” she recalls. “It’s definitely not easy. Not everyone is going to say, ‘This is brilliant. I can’t believe no one has done this before.’ You will hear many critiques, especially in the early days, but you know, you actually want that. You want all the feedback — to take it all in and build something better based on the questions and concerns you get.”

The startup’s success is a testament to Rad and Daneshmandi’s perseverance and commitment to creating a product that meets the needs of oncologists and patients. They worked closely with Dr. Bret Schipper, the chief of surgical oncology at Hartford Hospital, and took feedback and advice from industry stakeholders. Their background research also involved conversations with patients in various stages of cancer treatment.

Speaking with cancer patients about how Encapsulate could help them was a sobering reminder of the urgency of their work, Daneshmandi says.

“When you sit down and have a conversation with a patient who would eventually be using your technology, and you hear their stories, that’s when it starts to come into reality a little bit more. That’s when you realize you have the potential to change the life of someone who’s experiencing pain, unnecessary pain,” she says. “Those were difficult conversations.”

The talks galvanized them to bring their technology to market, and quickly. From conception to clinical studies, Encapsulate’s development process took about three years, according to Rad. The experience taught both researchers a great deal about maintaining conviction in an idea and working hard to clear the hurdles to helping others.

“I want to tell this to my young fellows at UConn, students who are dreaming about their own ideas,” Rad says. “You will find a way to persevere. It’s difficult, and there are many bumps in the road, but you will work hard and meet wonderful people along the way that make the journey enjoyable.”

Shooting for the stars

Daneshmandi and Rad netted an impressive number of awards from UConn, the state of Connecticut, and external organizations for their work with Encapsulate. Their research journey made them remarkably successful Ph.D. students: they graduated with a combined total of no less than six patents and 28 published papers. They are now completing their NSF Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Phase I project.

But perhaps the most exciting endorsement was the “Technology in Space” prize from Boeing and the International Space Station (ISS) National Laboratory, which will allow researchers to test Encapsulate’s technologies under the zero-gravity conditions of the ISS.

The company’s biochips are set to launch to the ISS this summer, according to Daneshmandi. The mission’s dual aims are to develop a universal platform for cancer research in the space station (which will require instruments that can perform analysis mostly autonomously, in a hands-off research environment), and to gain insight into chemotherapy in zero gravity.

“We know that cancer cells behave differently in space– because of the conditions of zero gravity – but we don’t know yet how that will affect treatment efficacy, and that’s what we want to explore,” Rad says.

Here on Earth, Encapsulate is busy with patient trials, exploring business development opportunities with partner companies, and gearing up for their next priced round to raise funds. Since graduating with his Ph.D., Rad has worked full-time as the company’s CEO, based out of its headquarters in Farmington. For her part, Daneshmandi has joined UConn’s faculty as an Assistant Professor in Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the School of Engineering and serves as the School’s Entrepreneurship Hub (eHub) Director. She also continues to work as Encapsulate’s COO, commuting between Storrs and Farmington.

The energy that first animated their partnership keeps them afloat through all the challenges of running a startup and conducting research.

“You’re chartering into this world of unknowns — it could tire you out. But at the end of the day, are you really passionate about solving the problem that you’re working toward? Do you wake up every day excited about what you’re doing? And is your heart really into it?” Daneshmandi says. “That’s what keeps you going.”