UConn John Dempsey Hospital and UConn School of Medicine have been at the forefront of teaching and using point-of-care ultrasonography (PoCUS), drawing instructors throughout the state, and teaching all pulmonary and critical care fellows in Connecticut.

The training is led by Dr. Jennifer Kanaan, associate professor of Medicine, Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine who has been teaching the statewide course since 2015 as well as Dr. Meghan Herbst, professor of Emergency Medicine who created the curriculum for the residency program at UConn Emergency Medicine and UConn School of Medicine.

PoCUS is ultrasonography performed and interpreted by the clinician to aid with decision-making and procedural guidance at the patient’s bedside. PoCUS is most widely used in emergency medicine and pulmonary critical care, UConn is now training its hospitalists, whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients, to aid in the rapid diagnosis of multiple medical conditions.

“There is some pretty remarkable data showing that when hospitals use ultrasound there is a change in diagnosis in 32% of cases and a change in management in upwards of 42% of cases,” says Kanaan. “The beauty of PoCUS is a physician delivering care at the bedside that can be repeated without adverse effects. This allows the provider to see how the patient responds in real time to various treatments through serial examinations,” says Kanaan.

In the Emergency Department (ED), PoCUS is used to rule-out or rule-in certain conditions that can be life-threatening and would otherwise take a significant amount of time to diagnose. PoCUS is used in emergency and critical pulmonary care to diagnose and categorize certain lung and heart conditions, trauma complications, hepatobiliary disease, ocular pathology, pregnancy complications, arterial aneurysms, vascular blood clots, skin infections, and many other disease processes.

Kanaan, who helps to educate all of the pulmonary critical care fellows statewide, has expanded that training to the hospitalists at UConn John Dempsey Hospital.

Dr. Jason Carrese, a hospitalist at UConn John Dempsey Hospital in internal medicine, is currently on track to complete his PoCUS training with Kanaan.

Dr. Jason Carrese, a hospitalist at UConn John Dempsey Hospital in internal medicine, is currently on track to complete his PoCUS training with Kanaan.

“Over the last two years there’s a growing trend in the field of internal medicine and hospital medicine that point-of-care ultrasound can also be used in this field too,” says Carrese. “Dr. Kanaan has taken the initiative to start training hospitalists at UConn on the use of point-of-care ultrasound, working side-by-side with hands-on training so that we can provide the best care for our patients.”

The hospitalist attends the two-day training course in PoCUS that Kanaan teaches to all pulmonary and critical care fellows, in addition, they attend sessions at least once a month where lectures, hands-on time, and mentoring happen. The hospitalists also perform what’s called a portfolio which includes getting images on their own that are reviewed together with Kanaan.

“It’s really pretty extensive and then at the end of their year-long PoCUS program they take an exam, complete directly observed ultrasound acquisitions as well as submit their portfolio,” says Kanaan.

During his training, Carrese has had some impressive finds using PoCUS. One of his patients had low blood pressure and when Carrese completed the PoCUS he found fluid around the heart that was compressing the heart’s chambers, compromising its function. The fluid was subsequently drained, which relieved the pressure on the heart’s chambers. Using a more traditional approach there would have been a lag time from when the ultrasound was ordered, performed by the cardiology technician, and interpreted so by using the PoCUS directly at the bedside he was able to find the diagnosis quickly and arrange for the patient to be effectively treated.

Another patient Carrese treated was experiencing arm and leg numbness with signs concerning a stroke and when Carrese performed the ultrasound he found a large blood clot within the heart, a condition that most patients do not survive, which expedited the appropriate management, improving this patient’s care in a way that other advances in medicine would not have caught as quickly.

“This training has justified itself in a short period of time especially on the weekends and at times of the day when traditional ultrasound is not available,” says Carrese. “Being able to do the ultrasound at the bedside has been a game changer for patient care.”

Carrese believes that PoCUS provides invaluable information by actually seeing the images of the lungs and heart to help understand what is going on and the best ways to treat it. It’s another tool for the doctor to use PoCUS to obtain real-time images and make clinical decisions. “For example, if a patient all of a sudden in the middle of the night becomes short of breath and their oxygen levels plummet, we can do something at the bedside to see if they have a blood clot or an extra strain on the heart,” says Carrese. “It provides invaluable information.”

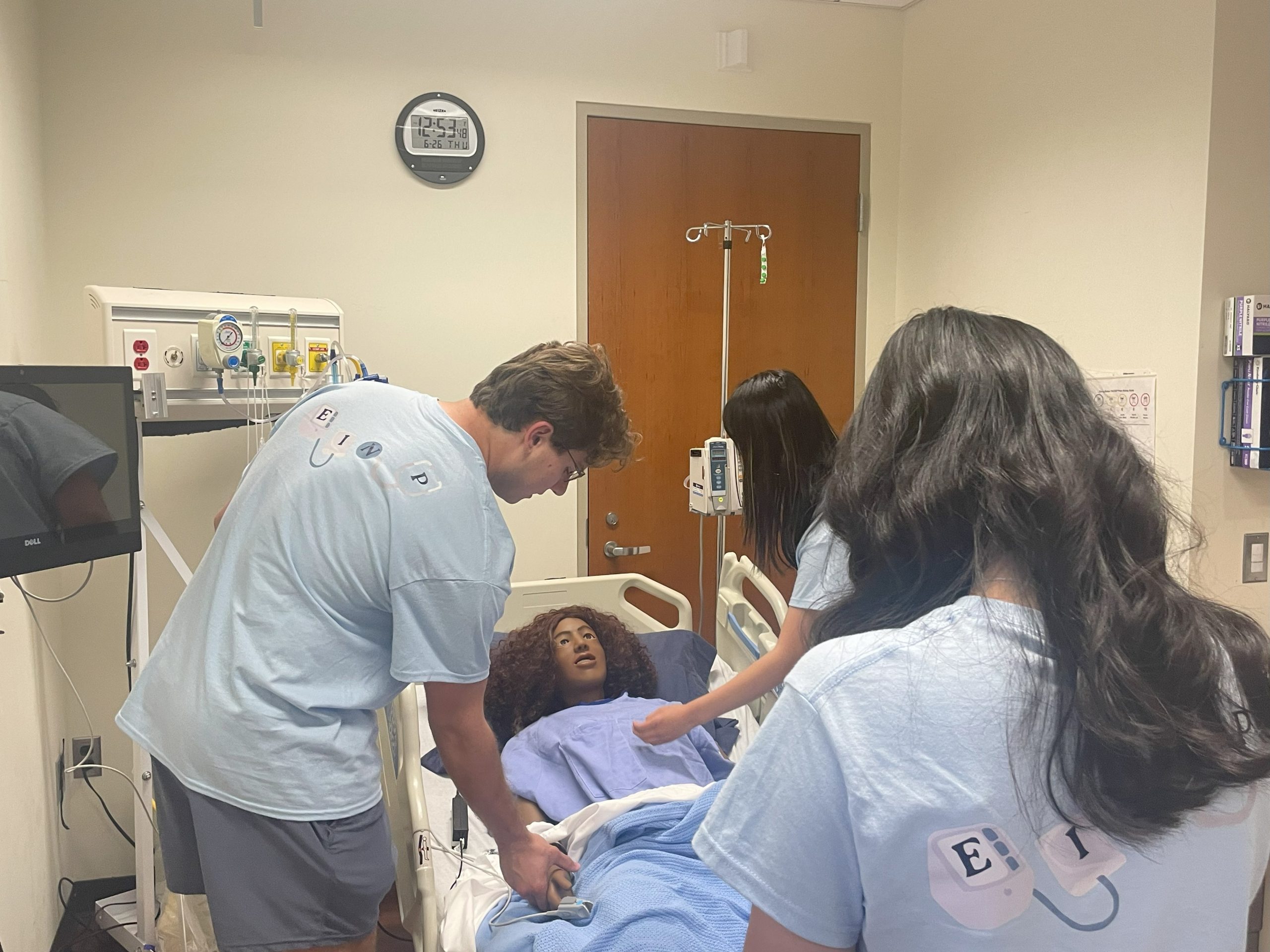

It’s not just in the hospital at UConn that this training is taking place. Medical students at UConn School of Medicine are ahead of the curve with a four-year vertical PoCUS curriculum that provides an ultrasound foundation for future practice. Over the past 5 to 10 years, medical schools across the country have started to incorporate ultrasound into their curriculum because so many medical residencies require their residents to use this technology.

In the first half of medical school, students are learning how to perform and interpret ultrasound on healthy human models alongside their traditional anatomy and physiology curriculum, such as cadaver dissection and other imaging modalities. Students have a flipped classroom model where they watch narrated videos in advance that show the ultrasound and have animated overlays then in class, they practice scanning in small groups proctored by Herbst, Dr. John Harrison, and Dr. Dharamainder Choudhary.

There are sessions throughout the third year of medical school that mimic what students will see in caring for patients. One example is when a patient comes in for abdominal pain, students run through a proctored session using the ultrasound skills they have previously practiced to determine the source of the patient’s pain. They may start by locating the gallbladder and if it is negative for disease, they may continue to look for the source of the pain by evaluating the kidneys. The answer to that case may turn out to be a kidney stone, in which case they can review the findings for that patient and move on to another case. There are several vignettes such as these to help run through various scenarios and use ultrasound to look for answers.

Students are also learning how to use ultrasound to guide invasive procedures like intravenous (IV) catheter placement. This skill is often needed when a nurse may have tried several times to place the IV but cannot because the patient is very sick or their veins are small, or their good veins are not very accessible. Ultrasound can identify the best vein and guide the IV so that the catheter can be placed with fewer attempts.

Then in the fourth year, students have an assessment where they independently perform various ultrasound examinations, including assessments for injury in the setting of trauma or low blood pressure. During this time, Herbst brings in specialists to work with students in small groups depending on what the students have applied to focus on during residency, such as critical care, surgical care, pediatrics, nephrology, and others.

“The trend over the past decade has just been to train everyone in the medical field earlier in PoCUS. This way, new residents will have had ultrasound training in medical school while current attending physicians actively get trained at the same time,” says Herbst.

She often hears from current faculty who want to learn this as their students are showing them what they have learned, and faculty find it amazing.

This year UConn School of Medicine students competed in SonoSlam© in Florida, an annual national medical student competition that includes ultrasound education, gaming, and competition among medical students. While competing in these events the past few years, UConn medical students have placed first more than once. This year was the first back since COVID, and UConn sent second-year students who were competing against fourth-year medical students, and they made it to the final four.

“I was so proud of these students because they were more junior competitors and they came so close to the top competing against students two years ahead of them,” says Herbst.

When UConn medical students head to their residencies, they bring with them a vital ultrasound education. This gives them a significant advantage. One recent graduate of the medical school who is doing her residency in Florida told Herbst that when they had their ultrasound orientation, she already knew everything they were teaching.

With Kanaan and Herbst, UConn is a pioneer in training PoCUS in the State of Connecticut, whether training its own medical students, residents, and faculty, or instructors and fellows throughout the state.

For more information on the advanced ultrasound course to be held on November 16, 2023, contact Amanda Pasler at 860-679-2129.