Even for Kenneth Fuchs, a Grammy Award winner who’s recorded at Abbey Road Studios and with the London Symphony Orchestra, every new piece starts with a sketch – pencil in hand, composition paper crisp and clean.

The process hearkens to the days when Fuchs was an undergrad and later a young musician, when he’d have fountain pen in hand, and would begin letters to artists whose works moved him: “Dear Martha Graham,” “Dear Leonard Bernstein,” “Dear Helen Frankenthaler.”

“I wasn’t just writing a fan letter. It wasn’t, ‘I love your music. Can I have your autograph?’ I never did anything like that,” Fuchs, professor of composition in UConn’s music department, says. “The first time I wrote to Stephen Sondheim in 1977, the summer before my senior year at the University of Miami, I wrote what must have been a four-page handwritten letter telling him not only why I liked his work but also what I learned from studying his scores. Those are the kinds of letters I wrote.”

Fuchs says that before penning that letter to Sondheim, he spent years poring over his musicals, memorizing their nuances and relishing their perfection. He’d become engrossed in the work and felt compelled to reach out.

He was young, impressionable, and seeking mentors when writing Sondheim and, around the same time, thanks to a visit composer Aaron Copland made to Miami in 1977, developing a friendship with Copland, arguably the best and most well-known of American composers.

Fast-forward 39 years, and Fuchs felt compelled to write again.

In the same way he devoured Copland and Sondheim’s works, Fuchs says he now was fervently consuming U.K. conductor John Wilson’s 2016 recordings of Copland’s ballets and symphonies.

“They were so original, like sandblasting the varnish off the interpretations that other people have done. They’re thrilling,” Fuchs says. “The music sounds brand new.”

And yet another letter-writing exchange began – one that’s led to today.

Dear John Wilson

With the John Wilson Orchestra, Wilson restored some of the lost scores from “The Wizard of Oz,” “An American in Paris,” and “Singin’ in the Rain,” taking what he could find – the conductor’s piano score, a violin part, or a scratchy recording – and recreating the music note by note.

“I’m amazed by his ability in both classical music and standard repertoire, early 20th century works by Korngold, Rachmaninoff, Ravel, and Respighi,” Fuchs says of Wilson. “I’m equally moved by his intuitive interpretations of American music.”

When Fuchs heard Wilson’s Hollywood renditions and later his Copland albums, he says he knew he needed to work with the British conductor one day. So, yet again, he put together pen and paper to express his admiration and hope they one day could meet.

In December 2018, two months before Fuchs won the Grammy for Best Classical Compendium, he wrote Wilson to tell him he’d be in the Netherlands just before Christmas and would like to stop in London to meet him.

Another meeting came in October 2019, shortly after Wilson had reestablished the Sinfonia of London, which, for several decades beginning in the 1950s, recorded nearly all the music for British film and television – think British spy movies – and comes with a reputation for hosting the finest musicians in the world.

Fuchs was working on music for his sixth album, he says, and wanted to ask Wilson if he could send him some scores, just for review: “I couldn’t even finish the sentence, and he said, ‘Ken, I promise I’ll record your next album.’”

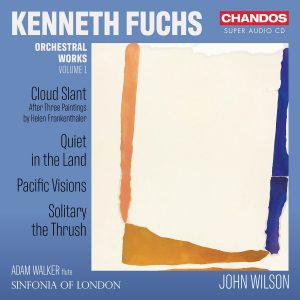

The album, “Cloud Slant,” was released July 14 by Chandos Records, debuting in the Top Ten of two Amazon U.K. classical bestseller charts — Most Wished For at No. 3 and Best Sellers at No. 8. It also has received numerous four- and five-star reviews, including one in The London Sunday Times.

It includes “Solitary the Thrush,” a concerto for C and alto flute and orchestra based on a Walt Whitman poem; “Pacific Visions,” an eight-minute piece for string orchestra; and “Quiet in the Land,” described as a poem for orchestra.

The title work is a concerto for orchestra, using for inspiration three Helen Frankenthaler canvases, “Blue Fall,” “Flood,” and “Cloud Slant” – a 19-minute ode to a longtime friendship between Fuchs and the abstract expressionist painter whose words of encouragement inspired a young Fuchs to find his musical voice.

Dear Helen Frankenthaler

“I think about her a lot,” Fuchs says. “When I’m writing a Frankenthaler piece, I remember how she talked to me about taking risks. She always said, ‘There are no rules,’ and what just knocked me out was when she said of her work, ‘You learn everything that painting is about, craft and technique and artists whose work inspires you, and then you throw it all out.’ And I thought, what an inspiring idea, to gain the craft and then not be burdened by it.”

Frankenthaler and Fuchs became friends in 1983, when he was a grad student at The Juilliard School in New York City and still developing the type of music he wanted to write. He says that when he saw his first Frankenthaler canvas, “Out of the Dark,” he found his sound: “It was like a visual impression of what I wanted my music to sound like.”

Frankenthaler, who died in 2011, was a second-generation abstract expressionist painter, and layered wall-sized canvases with turpentine-thinned paint to create a color wash mimicking the look of watercolor.

“I saw ‘Flood’ at the Whitney Museum for the first time in 1984 and went back countless times to study it. I’d stand in front of the painting, imagining which gestures came in what order,” Fuchs said. “I could see that she poured this here, and then she stained that over there, and then she created this veil.”

Much like Fuchs composes music.

“I play a chord on the piano, write that down, and keep making harmonic sketches of different variations on that chord,” Fuchs says. “While I’m doing that, I hear the music in my head. That’s a gift, nobody knows where it comes from, but you respect it. When I start sketching, I begin with a harmonic idea, then a melodic idea will occur to me, and I’ll write that down. Then, I’ll write ‘flutes and violins’ on the paper, just as an idea. I keep doing this, little by little, over three, four, five, six weeks at the piano and end up with 20 pages of sketches. Only then do I make the score in music-notation software and start composing directly into the score at the computer from the sketches I made.”

He continues, “When the score is done, I look through all the parts – the woodwinds, brass, percussion, and strings – from start to finish, one at a time, to see if there is enough music for that instrument or whether I left something out. I always ask myself, ‘Does the part by itself make sense to the player?’

“My gift, I hope, to any player is when they’re in the practice room that they’re playing something that is gratifying and idiomatically composed,” he adds. “There’s no sin in writing difficult music. The sin comes when you write music that doesn’t fit the instrument and the player wastes their time figuring out how to make it sound good.”

When Fuchs uses a Frankenthaler painting as inspiration – like with “Cloud Slant” – he says he lays the work nearby, most often the open pages of an exhibition catalog, to draw from its emotion.

“It’s not just trying to write music that imitates what the painting looks like,” he says. “It’s deeper than that. I try to get to the substance beneath the surface and transform that into musical language – creating understandable gestures, which is what abstract expressionism is all about. It’s what music is all about.”

In 2003, as Fuchs started to record his compositions, he turned to Frankenthaler in a letter to ask whether he could use her paintings. She agreed.

Since then, they’ve not only been muse for song, but also have served as cover art for the five American Classics albums Fuchs recorded for Naxos Records, including the Grammy Award-winning “Piano Concerto, ‘Spiritualist’/Poems of Life/Glacier/Rush.”

“I don’t own an original Frankenthaler, but what I do have is friendship,” he says of her influence. “She always invited me to her gallery shows in New York. I was awestruck to be in the same room with someone who not only was famous but whose works I admired so much.”

Fuchs recently donated 30 years’ worth of handwritten correspondence between the two to the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation for preservation.

Meanwhile, this summer and into next winter, as Fuchs and Wilson continue work on a second volume with the Sinfonia of London, expected in June 2024, Fuchs is engaging in another letter-writing campaign – this one for a chance at Grammy nominations for “Cloud Slant.”

“Such things don’t happen by themselves,” he says. “As with film studios and actors campaigning for awards, it’s the same for classical music. I’ve learned that if you want to get serious about winning one of these awards you, too, have to develop a campaign. You can’t just put it out there and hope that people will vote for it.”

While this letter-writing effort might be more business-focused right now, it’s no less full of admiration than the other notes Fuchs has penned over the years. He says he’s humbled to be considered among the top 21st century American composers, and even to be a peer in a class of friends he’s made along the way.

“Music is about dramatic narrative and storytelling. It’s about a dramatic throughline that’s understandable,” he says, “in much the same way as a well-written letter.”