In our recurring 10 Questions series, the Neag School of Education catches up with students, alumni, faculty, and others throughout the year to offer a glimpse into their Neag School experience and current career, research, or community activities.

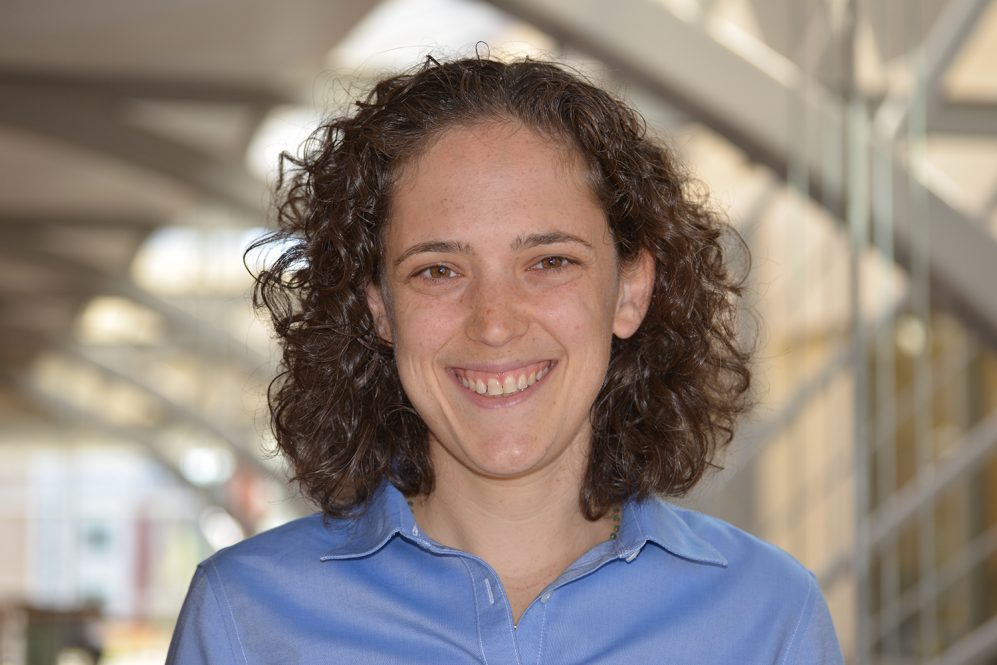

As a professor of literacy education and director of the Neag School’s Reading and Language Arts Center, Rachael Gabriel recently published “Doing Disciplinary Literacy” through Teachers College Press. She is the author of more than 50 refereed articles and author or editor of six books for literacy teachers, leaders, and education researchers. Gabriel currently teaches courses for educators and doctoral students pursuing a specialization in literacy. She serves on the editorial boards of journals focused on literacy, education research, and education policy. She has also served on the boards of the International Literacy Association and the Reading Recovery Council of North America.

In addition to experience as a classroom teacher and reading specialist, Gabriel holds graduate certificates in quantitative and qualitative research methods and a Ph.D. from the University of Tennessee in literacy studies. Gabriel’s research is focused on literacy instruction, leadership and intervention, and policies related to teacher development and evaluation. Her current projects investigate supports for adolescent literacy, state literacy policies, and discipline-specific literacy instruction.

In this feature, we explore Gabriel’s new book and the importance of its topic.

Q: What is disciplinary literacy (DL), and why build it? How does discipline-specific literacy instruction increase academic engagement?

A: Disciplinary literacy instruction (DLI) is instruction aimed at engaging students in the activities of the discipline(s) they study. It represents an orientation to the purpose of instruction in the disciplines as focused on using content knowledge and skills to do and act in the world rather than only to know or remember.

Q: In the book’s acknowledgments, you mention Chris Wenz as “flipping on a light switch for putting disciplinary literacy into a spotlight.” How did his work impact your academic path?

A: Chris was one of my doctoral students in my first few years at UConn. He once asked for an extension on a project to investigate a topic that we had only spent one or two classes discussing. The topic was disciplinary literacy, and his framing of it as an entire orientation to instruction rather than a single set of strategies showed me how much more I needed to learn.

Q: Who were your biggest supporters of this book and why?

A: I proposed a version of this book my first child was born. Two kids and two dogs later, it took a lot of patience from my editor at Teachers College Press and my family. I note in the dedication that it took the freedom and support of department chairs and program directors to allow me to continuously teach and redesign courses related to Disciplinary Literacy in the Neag School’s teacher preparation and literacy specialist programs over a decade.

Finally, but perhaps this should be first, in my first year at UConn, Dean Jason Irizarry offered to read and give feedback on a book proposal I was working on and followed through on it, with handwritten comments on the printed copy I left for him in his department mailbox. It seems like this happened in another century. His comments were clear and encouraging, and it meant a lot to me to have his guidance. His example and my experiences over the next few years led me to abandon that first idea, leaving room for this one to develop. I still have those papers with his comments on them in my office.

Q: How did the idea of the book come about?

A: DL is a relatively new area of inquiry for K-12, though it has been around much longer in higher education settings. So, there needed to be more course texts to choose from when teaching these courses. This book is the textbook my colleagues and I wished we had made of many of the activities, ideas, and frameworks we developed to teach these courses at this time of development for the field.

Q: If you were to look back at the process, would you do anything differently and why?

A: There are a lot of texts that need to be written about DL, and I can only write one of them at a time. I would give myself permission only to write one at a time and not worry or wonder whether I have or am ready to write everything yet.

Q: What did you learn along the way? How does this book compare to the other you’ve written or edited?

A: It had been ten years since I published a book as a solo author. I spent a lot of time thinking how hard it was for all the ideas and motivation to come from inside one person and then realized there’s no such thing as solo when it comes to writing in academia. We are always conversing with other people’s ideas, evidence, inspiration, and language use. Once I remembered it’s not me and I’m never writing alone, the process became much faster and more enjoyable.

Q: What is the Oak Tree Activity, and what’s the importance of it?

A: The Oak Tree Activity offers a metaphor for the interactive relationships between foundational skills and increasingly sophisticated linguistic and metalinguistic knowledge that governs language use in different settings. Educators can parse the language levels present in any given text or create their text to identify how these layers interact and can be used to inform one another.

Q: What are some activities to support students in developing the meta-discursive awareness, or understanding of language, that allows them to navigate the texts of different disciplines?

The idea that all text has a purpose and audience – even if distant, assumed, or forgotten – helps reorient us to how language is used to do things. Understanding how language is used is key to developing awareness of its use.

The book is designed for that kind of reading, which lends itself to a professional learning community or course spread out over weeks or to a weekend spread over times of day and places to read. — Rachael Gabriel

Q: What are some strategies to strengthen teachers’ awareness of disciplinary text, practices, and habits of mind to inform how they model, teach, and invite literacy into their classrooms?

A: One great place to begin is to consider who uses a particular content focus to do things in the world and ask what texts surround that use. If you’re starting with a particular text, wondering who uses it and how — what the purposes, audiences, and formats for its use or production include — can inform the approaches and strategies used to read or write it.

Q: Why is this book important to educators? Who can benefit from the book, and how can educators utilize it?

A: This book is written for individual or group study of DL and ways to incorporate it into classrooms. It’s not a beach read, manual, or a toolkit. It’s meant for people who want to bite off and try a piece of this to see where it takes them. So, you can dip in and out of it. You can read it as background or follow and do the activities to build your understanding and make it particular to your classrooms. I’m excited to see what educators create using these ideas as a foundation to build on rather than a roadmap of what to do.

Snack on it. Dip in and out. Chew on ideas. Try things and come back to them. The book is designed for that kind of reading, which lends itself to a professional learning community or course spread out over weeks or to a weekend spread over times of day and places to read.

To learn more about the UConn Neag School of Education, visit education.uconn.edu and follow the Neag School on Instagram, Facebook, X, and LinkedIn.