Brandi Simonsen can skillfully sum up the fundamental tenets of the school behavioral support system to which she has devoted her research career: “The idea is setting every kid up for success, and directly teaching the social, emotional, and behavioral skills they need in school and beyond.”

In the classroom, Simonsen explains, this translates to teachers and students explicitly teaching and learning shared positive behavior expectations, like being kind, and recognizing students for modeling these values, “instead of waiting for a kid to make mistakes and then correcting them.”

Simonsen co-directs the National Technical Assistance Center for Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (Center on PBIS), along with Kent McIntosh of the University of Oregon and Heather George of the University of South Florida. Other UConn faculty and research associates affiliated with the Center on PBIS include Jen Freeman, Susannah Everett, Katie Meyer, Karen Robbie, and Nicole Peterson.

The US Department of Education has recently awarded $21 million to the Center to support its programming over the next five years, representing a substantial federal investment in the continuance and expansion of the program.

“For many of my mentors, PBIS as an approach came out of the experience that they were often being called in to work with individual students who were struggling. And there was a missing piece where folks were not understanding that the kids were struggling because the system wasn’t working for them,” says Simonsen, who is a professor of special education in the Neag School of Education. “This mentality affects the kid. The approach that we have been advocating for, instead, is how do we fix the environment to be more supportive of students?”

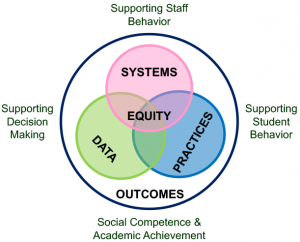

Researchers at the Center believe that the PBIS model is uniquely suited to respond to the challenges of K-12 education in the twenty-first century, especially following the multiyear classroom disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic. PBIS integrates cutting-edge research on best practices in education with a focus on equity and cultural competence. To date, it has been implemented at more than 27,000 US schools.

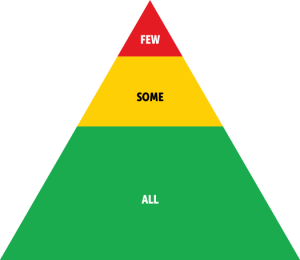

When PBIS systems are implemented with fidelity, schools report marked benefits – greater wellbeing for both students and teachers, increased academic performance, decreased incidences of bullying and student-reported drug/alcohol abuse, and decreased reliance on exclusionary discipline measures like principal’s office visits and suspensions. Following the framework means that students are more able to remain a part of the classroom community, as behavioral challenges are understood holistically and addressed with empathy.

For Simonsen, the most important part of her work with the Center is not how many papers it publishes or how much funding it receives (though the numbers are impressive on both fronts), but “how I can make sure that kids actually experience better days in their classroom contexts.” She is a parent of two school-aged children herself, and says that she’s been able to chart the effects of PBIS implementation on her kids as more local schools have adopted the framework.

“As a family member, it has all been really positive to watch,” she says. “My kids are having the benefit of these experiences, and their schools are making efforts to support all students’ social, emotional, and behavioral needs through PBIS.”

With the latest round of funding, Simonsen will continue her work solidifying UConn as a hub for PBIS research and support for the entire Northeast, where it supports a regional network of state leaders.

The Center provides technical assistance to states as they support implementation of PBIS, while emphasizing the importance of districts and schools adapting the framework to their own contexts. The Northeast region, with its relatively small and numerous states, is especially well suited to leveraging resources and expertise across state lines, Simonsen explains.

The other principal use of the renewed funding will be “to increase and enhance the focus on equity, specifically around racial equity; folks who identify as LGBTQ+; and students with disabilities,” says Simonsen.

Equity has always been a cornerstone of the PBIS framework, but the social and research progress of recent years has allowed PBIS experts to sharpen their focus on all aspects of educational equity.

“We’ve always given the message that we are talking about all kids — even when we were funded solely from Office of Special Education dollars, we have always been talking about increasing the support for all students,” Simonsen says. (The Center is now funded jointly by the Office of Special Education and the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education.) “National data in the last decade-plus has been very clear that we have to have conversations about racial equity; mental health and climate data are clear that, in addition to race, we have to be looking at gender identity, sexual orientation, disability. The gaps in people’s experience of school are substantial based on how they identify.”

When asked about the “why” behind her research and work with the Center, Simonsen’s passion for student experiences shines through.

“I really think it’s the fact that it’s so transformative for the experiences kids have in schools,” she says. “Being able to support states and districts in creating classroom environments where kids feel like they belong, and they have the supports they need to be successful, and – regardless of where their ability level is or what else is going on in their life – they come home with a successful experience in school, the ability to make friends, to think about the future, and all of those pieces. Being able to scale that and have that impact felt and experienced by more kids is what I’m the most excited about.”