When Catherine Masud was young, maybe 9 or 10 years old, she happened to be home alone after school one day when two men wearing sunglasses and long dark trench coats, dressed as if they were out of a movie, showed up on her family’s front stoop in inner city Chicago.

The front door of the home was a full pane of glass, completely see-through and screaming for curtains by today’s standards, she says, so there was no hiding from the men who showed her an FBI badge and asked for her mom.

“She’s not home yet,” she told them. “Can I ask your names?”

“No need for names. Just tell her we’ll come by another day.”

Masud says she watched as the men turned and walked away, down the sidewalk and into a dark-colored Cadillac parked on the street, then drove away.

The minutes-long encounter might have rattled anyone – young or old.

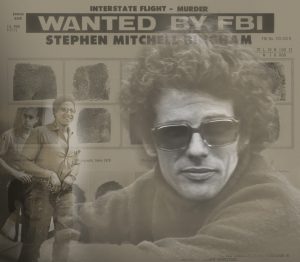

For Masud and her family, though, the FBI at that time surveilled much of their lives, tapping phones and tracking whereabouts as government agents searched for Masud’s uncle who was accused of passing a gun to prisoners’ rights leader George Jackson and sparking an uprising at San Quentin Prison in 1971.

“I was told you never talk to your friends about this,” Masud says of the FBI and the story of her extended family. “I was told you never mention the name Stephen Bingham to anyone.”

‘The past is never dead’

An assistant professor-in-residence jointly appointed in UConn’s Department of Digital Media & Design and the Gladstein Family Human Rights Institute, Masud was 8 when her uncle vanished from his life in California after the tumultuous events of 1971 when Jackson, three correctional officers, and two inmates were killed.

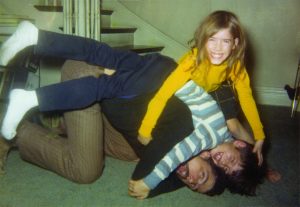

She says she and her brother didn’t really understand what had happened, especially since Bingham had visited Chicago only a few months prior, roughhousing with the children in favorite uncle style.

“I grew up thinking he was probably dead,” Masud says, noting that even her grandparents in southeastern Connecticut contended they didn’t know what happened to their youngest child. “But the FBI kept coming by our house and our phones were tapped, so you could say it cast a shadow over my childhood.”

Nonetheless, as children do, Masud grew up. She went to college at Brown University, then went to work for an overseas nongovernmental organization.

By the time Bingham returned home, turning himself in to police and later facing charges of first-degree murder, Masud had settled in South Asia where she made films with her Bangladesh-born husband, Tareque. Geography stymied a chance to reconnect, more than just hearing about one another in family circles, until a few years ago when she herself came home.

What did he do all those years?

What was it like to assume a new identity?

Who was this person he’d become?

“I approached him about telling his story in a documentary. He waffled at first and said he wasn’t sure he wanted to talk about it,” she says. “He said that what happened was in the past. But as I found out later, it was very much in the present for him. The past is never dead.”

Over the course of three long interviews with Bingham, Masud learned about her uncle’s involvement in the Freedom Summer Project in 1964, his work with Cesar Chavez and the farm worker strikes in California, and his early career as an advocacy lawyer.

She answered the questions of what he did during those 13 years, where he went, and how he survived. She learned about his French wife, his continued activism, his child.

And in interviews with his legal team, friends, family, acquaintances, and supporters, she learned so much more about the Stephen Bingham who she remembered only as the fun uncle who wore a leather jacket and rode a motorcycle.

Telling more than just one story

“A Double Life,” which premiered late last year and will be screened at UConn in April, lays out not just Bingham’s story, but considers the roles of lawyers in social movements and how racial tensions in America in the late 1960s and early 1970s affected so many aspects of life, including Bingham’s case.

“The family is also part of the story,” Masud says. “There are intergenerational tensions that were important to talk about and it was important to address the legacy out of which Steve came – this background of white privilege, grandson of a U.S. senator, son of a state senator.”

Throughout the film, Masud lets Bingham and his associates tell the story, interjecting as narrator only a few times. The film isn’t her story after all.

Privately, hers is one of speculation: Could she have walked by her uncle on the streets of Paris in 1983 when she was studying there abroad? It’s also part shared experience: Both had close loved ones, a husband and a daughter, killed by motor vehicles in different years and different places, and still both found strength in that loss to fight for improved road safety.

“I remember the moment I met Steve after he came out of hiding because I have this visual of him kind of backlit and all I could see was his hair. Somebody said to me, ‘Oh, here’s Steve.’ I couldn’t believe I was meeting him, and he was walking toward me. It was very strange because here was this person who all these years I thought was never coming back and might even be dead, yet there he was,” she says.

Masud says that even nearly 30 years later, as she was getting up the nerve to approach him with the idea for a documentary, she was intimidated – her, an award-winning filmmaker who’s worked with survivors of mass atrocities and genocide.

“Even though he’s a very warm person, he’s also sometimes reserved or standoffish. I think that was part of the change that happened in his personality because of the time he spent underground, always being on guard, always looking over his shoulder,” she says.

She also says she hesitated in asking him because she didn’t want to be the source of more trauma as Bingham relived his past. But realizing time heals and older age often prompts reflection, now ended up being just the right time for the project – for both of them.

Masud is back in the United States, rebuilding a life here after her husband was killed in 2011 in Bangladesh along with most of her film crew. “A Double Life” is her first feature-length project in the U.S.

“I was in Bangladesh for most of my adult life with almost a different identity. It wasn’t a secret identity, it wasn’t underground, but it was a bifurcated existence because when I came back here, I felt like a foreigner,” she says. “I could identify with what it must have been like for Steve. He was completely immersed in the culture of a different place. It was similar for me.”

She says Bingham doesn’t regret the years he spent living underground and would have regretted only not returning to the U.S. His father, Masud’s grandfather, paid his annual dues to the bar association, so Bingham wouldn’t lose his license and could go right back to practicing upon his return, should he return.

“If this film gives audiences some insight into what Steve went through, if it gives them some inspiration and teaches them the importance of sticking to your principles even through adversity, then I’d be happy,” she says. “I would be glad if it gives them a deeper understanding of not just a particular historical period but how that resonates in the present and what we have to learn from that.”

“A Double Life” will be screened Monday, April 1, at 4 p.m. in the Konover Auditorium in the Thomas J. Dodd Center for Human Rights. It was screened at the Pan African Film & Arts Festival in January and the Mill Valley Film Festival in October, where it won an Audience Favorite Award.