Haiying Tao ‘07 Ph.D. has pursued her interest in agriculture across two continents. She studied first at China Agricultural University, where she received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and then at UConn, where she received her Ph.D. in soil science. These days, you can find her in her office in the W. B. Young Building, if she’s not working on the Research and Education Farm off Agronomy Road or on private farms.

Tao’s research is currently garnering more nationwide significance as part of the Fertilizer Recommendation Support Tool, or FRST (pronounced “first”). FRST is an online national soil fertility database funded and hosted by the USDA. When complete, it will include past and present soil test data from researchers across the United States, including phosphorous and potassium levels, locations, soil type, fertilization trends, and yield outcomes for specific crops.

As an assistant professor of soil nutrient management and soil health in the College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources, Tao teaches agriculture students the questions and methodologies that turn problems into solutions for farmers at all scales. Her research helps propel academic agricultural knowledge into real-world applications for the farmers who feed the country.

Providing Growth Support at the Ground Level

There’s a reason why the middle of the country is often known as “America’s breadbasket” – a farmer’s ideal landscape is vast, open, and flat.

These conditions are not always met in more coastal farmlands, which can include sections of varying soil composition, quality, and slope. Fortunately, precision agriculture techniques can enable farmers to tailor their fertilizer application across an entire field.

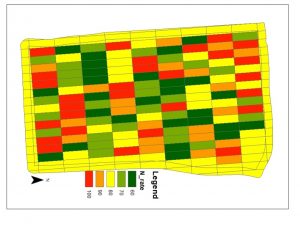

Factoring in variables like topography, climate, management practices, and soil properties, precision agriculture divides a field into discrete sections using a grid system. This essentially creates a paint-by-numbers guide for smart farm equipment, which can then use this map to control how much fertilizer is applied to each square.

In on-farm precision experimentation, Tao uses this and other modeling methods to help farmers test the success of various fertilizer application rates so they can develop the most efficient fertilization strategy for their whole field.

Tao’s eventual goal with this research is to develop a software that can easily generate these strategies for farmers. The envisioned program will allow farmers to “simply input their field information in the app or software, and then the software will spit out the variable rate recommendation map,” Tao says.

From there, farmers would upload the map into their existing sensing and smart fertilizing equipment “and then just drive and apply their fertilizers at the right rate and at the right place.”

Updating Guidance for a New Generation of Farmers

With FRST, Tao is helping bring national crop fertilization guidelines into the 21st century.

“If you look at the current recommendations, they are all based on very old research trials,” says Tao — the last such nationwide survey was in 1998. “But now, our climate is different, our soil characteristics are different, our [crop] varieties are different, our management practices are different. The whole system is somewhat different from 20 years ago.”

Tao is specifically interested in fine-tuning the recommendations for nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium application — three essential nutrients replenished by fertilizing the soil — and providing new data to FRST.

“We call them essential nutrients because without them, the crops will not be able to complete their life cycle — and they are not replaceable by any other elements,” she explains. “So, if crops are deficient in these nutrients, the yield and quality will be compromised. But how much is needed, and how much farmers should apply, is based on recommendations from land-grant universities.”

Generating these fertilizing recommendations will not only help farmers achieve greater crop yields, but also allow them to reduce costs and improve soil health by ensuring that they apply only as much fertilizer as the crops require at any given location in any given year — no more, no less.

According to research from UConn’s Zwick Center for Food and Resource Policy, guidance and support from land-grant universities like UConn has become even more crucial in recent years, as climate change, state regulations, and difficult economic conditions all challenge domestic farmers. And, since Connecticut farms provide approximately 22,000 jobs (at last official count, which was in 2017) and account for 8% of state residents’ food purchases, protecting these farms benefits the whole state.

While she performs her meticulous field experiments, Tao is glad to know she’s giving farmers one less thing to worry about as they look toward a changing future.

“The goal is to improve the accuracy and precision of nutrient recommendations so that we can help producers adapt to extreme weather events and build resilience for climate-smart agriculture production systems,” she says.