As if poet Emily Dickinson wasn’t distinctive enough for the 19th century, her very own handwriting also gave away the poet’s rebellious nature.

“She had a man’s handwriting,” says Thomas Long, a professor emeritus who taught writing in UConn’s School of Nursing. “Her handwriting was big and loopy, even her contemporaries commented on that.”

During Dickinson’s life in the 1800s, Long says, men and women were taught different penmanship styles. Men would learn to make broad strokes, while women were instructed to keep letters diminutive to match the way they were expected to be: petite, quiet, unassuming.

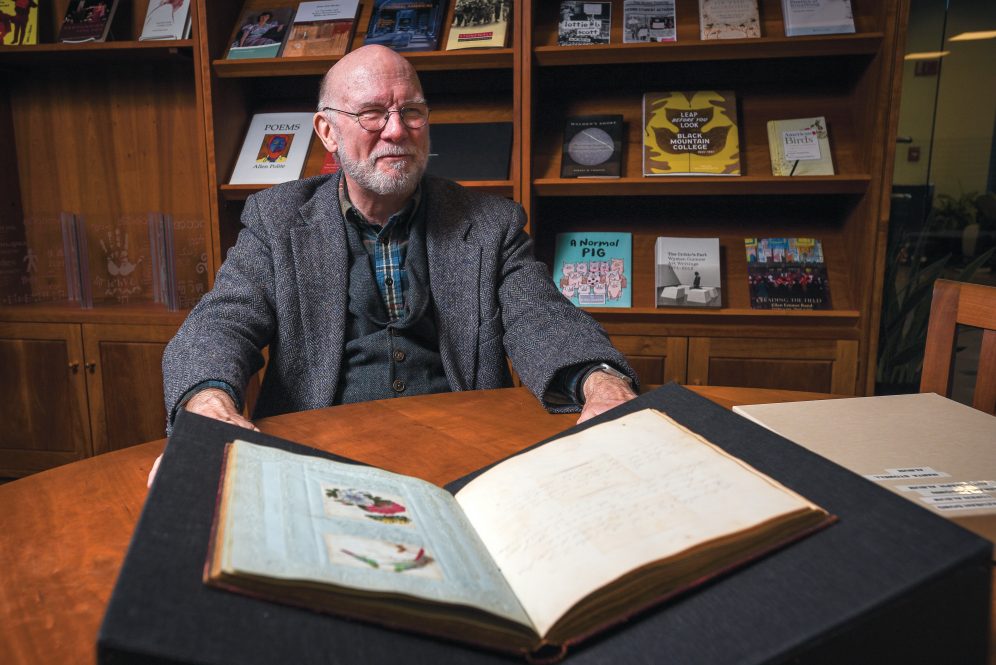

Long’s collection of more than a dozen mostly anonymous scrapbooks from that time – more precisely, penmanship fascicles, commonplace books, and friendship albums – offer example after example of handwriting from the time, much of it female script and, unfortunately, none of it from Dickinson.

But the personalized books, which Long has donated to the UConn Library and Archives & Special Collections, are part of a 19th century practice Dickinson would have known about and in which she may very well have participated.

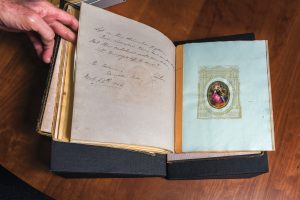

“People would have passed these books around, in some cases carrying them from town to town, for others to write things in them – verses that were memorized, poetry you wrote, quotable quotes that were overheard. Sometimes you can find pressed flowers between the pages or even small sketches. Also, when people came to visit, they would sign the books, so they served as autograph books, too,” Long explains.

Eventually, book publishers caught onto the practice and began to print blank books with leather covers, much like today’s journals, maybe peppering in empty pages of music staffs or embossed frames screaming for creative attention.

But oftentimes, people handstitched together scraps of paper, a prized possession of the simplest kind.

It’s no wonder, Long contends, that Dickinson left behind such handsewn fascicles with hundreds of her poems in a dresser drawer when she died. Her means of publishing wasn’t eccentric; simply a popular, deeply personal, method for the time.

“Self-publication in handwritten booklets was a much more common way of writing than had been originally thought. It’s the mainstream way 19th century women were published,” Long says. “When you look at these books, you’re seeing what people read and loved. This is the lived experience of poetry in people’s lives.”

Back then, he says, poetry was everywhere in society. It was published in the daily newspaper and sung during Sunday church services. Even today – as the country recognizes National Poetry Month in April – music playlists include songs replete with poetry, and social media posts are captioned with inspirational poetic snips.

Long says poetry is important, first, for pleasure, the simple joy of reading verse, and second, to commemorate the big, beautiful, and dramatic turning points in life – death, birth, marriage, graduation – if only in a greeting card.

“Oftentimes they’re trite, silly, and sentimental,” he says of greeting cards, “but the fact is we turn to poetry in life’s intense moments. There is no more noble medium for expressing the mystery and intensity of our lives. It takes us out of the everyday. The lines of a poem speak to us in a way that a paragraph of prose would not.”

Decades ago, Long happened upon the first commonplace book of his collection at an antiques show in Virginia Beach, the same one where much later he discovered a page from the famed Beauvais Missal.

He describes the initial find as a homemade anthology of verses assembled by someone who lived in Massachusetts. One poem is titled, “Formation of a Lyceum,” another is dedicated to someone called Little Willy. There’s one written on the death of Miss Cogswell and another written on the death of someone named Ranny Harris.

“It was only a little Black girl, for whom the bell did toll,” he reads of Ranny Harris, noting the historical importance of such a poem in antebellum New England.

“Tom has a way of filling the gaps in our collection,” Melissa Batt, an archivist at the Archives, says of his donation. “These are wonderful documents of 19th century writing practices, but they also tell us about the networks of females who contributed to them, the friends, family, mentors, perhaps even lovers, with whom these women circulated.”

In some of the books, the authors practiced their penmanship, Long says. They pressed in newspaper clippings of poems and other items. In one, someone pressed a clover and on the next page another sketched a flower.

Long picks up a book he found among a lot of miscellanea in Plymouth, England, a gift from 19th century playwright James Sheriden Knowles to someone named Jemma Haigh. There are autographs from various people and a pressed lithograph inside.

“Scrapbooks are a way of making meaning of a period in your life – girlhood, young adulthood, a change in one’s life, graduation,” Batt says. “This collection draws us into bigger questions about history and tells us something about the assemblers and the way they’re processing what’s happening around them. It’s really a form of journaling.”

When UConn students visit the Archives for classes and she brings out various objects for study, Batt says the scrapbooks and friendship albums are what they’re drawn to most. Perhaps it’s what they can relate to, she posits.

But what about those who find poetry inaccessible?

“You were schooled during the ‘interpretation regime’ that said there are secret meanings in poems,” Long suggests to someone. “The hunt for hidden meanings gives most of us a headache. Why not look at poetry just for pleasure?

“One of my favorite lines comes from the French poet Stephen Mallarme,” he continues. “It translates roughly to, ‘To precise a meaning erases your mysterious literature.’ Poetry is meant to be lived with and loved. It’s really that simple.”