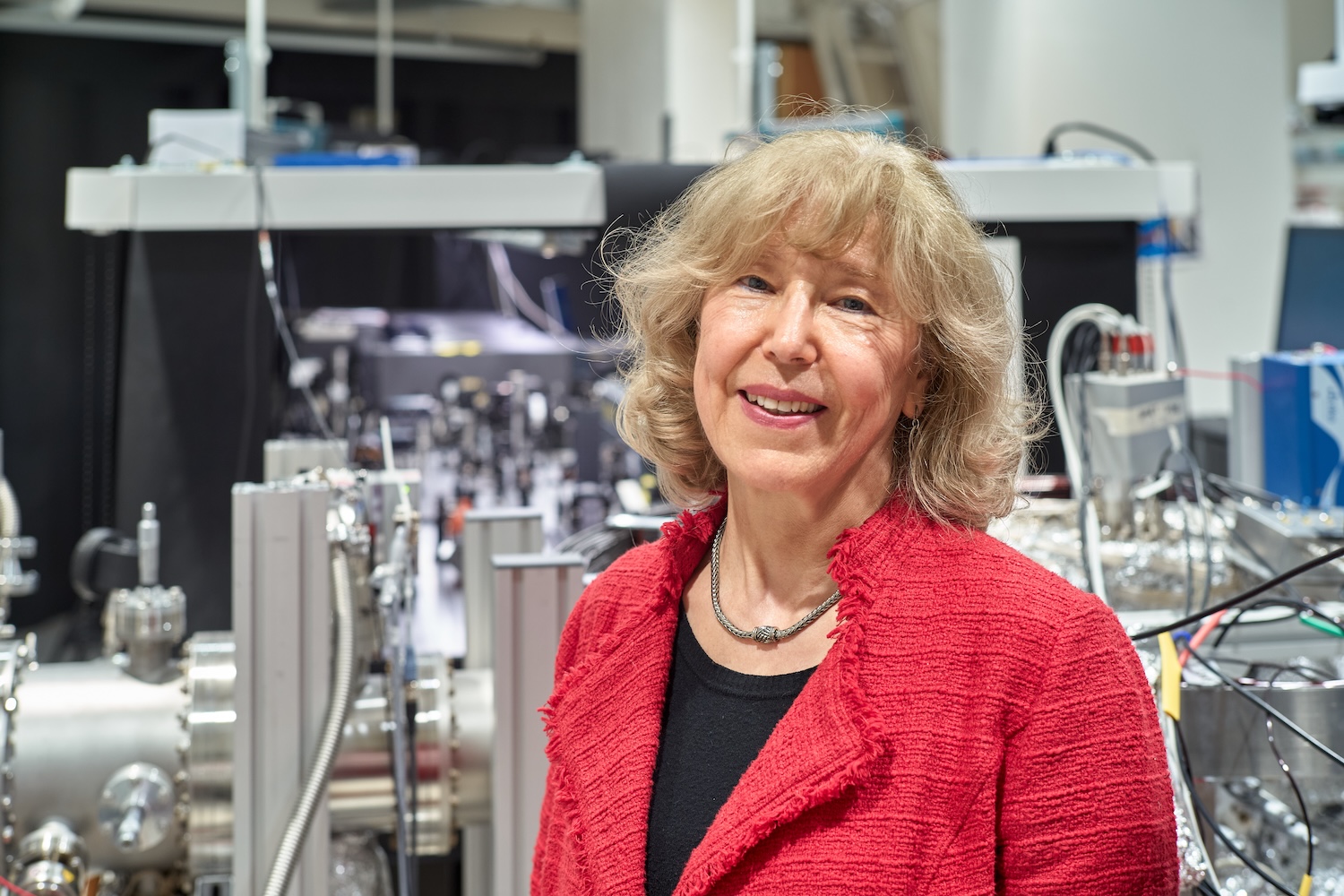

UConn physics professor Nora Berrah has been elected as a member of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), becoming the seventh member from the UConn community to join the selective national society.

The Society was established in 1863 by an Act of Congress and signed into law by former President Abraham Lincoln as a private, nongovernmental institution.

Members are elected “in recognition of their distinguished and continuing achievements in original research,” and the academy serves as an advisory board for the nation on issues relating to science and technology.

As a member of NAS, Berrah joins faculty and emeritus faculty members Kathy Segerson, professor of economics; Dr. Cato Laurencin, Chief Executive Officer of The Connecticut Convergence Institute for Translation in Regenerative Engineering at UConn Health; Laurinda Jaffe, department chair and professor of cell biology at UConn Health; Dr. Se-Jin Lee, Presidential Distinguished Professor in the Department of Genetics and Genome Sciences at UConn Health; Mary Jane Osborn, professor of microbiology who died in 2019; and Henry N. Andrews, professor of botany who died in 2002.

“Membership in the NAS is one of the highest honors that can be given to a scientist,” says Ofer Harel, Interim Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “It is a recognition by peers and the academy of outstanding research achievements, and Nora absolutely falls into that category.”

Current academy members must nominate and vote for new members to join the academy, with no more than 120 members being elected each year.

“It’s just an unbelievably great honor,” says Berrah. “I feel very grateful for all the National Academy members who voted for me and for being elected.”

Berrah, the former department head of physics from 2014 to 2018, was elected in recognition of her research that focuses on ultrafast physical and chemical processes in quantum systems.

Berrah’s research has wide ranging impact

In her lab on campus, as well as at the Linac Coherent Light Source Free Electron Laser at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Stanford, California, Berrah conducts “time resolved, photo-induced experiments to understand ultrafast fundamental mechanisms such as charge transfer, energy transfer, and proton transfer.”

The experiments measure super-fast reactions up to the femtosecond, or one quadrillionth of a second, as well as to the attosecond, or one quintillionth of a second which has important impacts on other scientific fields.

“We want to understand these processes, and ultimately we want to control them to achieve desired outcomes,” says Berrah. “I and my research group measure manifestations of quantum mechanics — using ultrafast lasers at the femtosecond and attosecond timescale to test fundamentals of quantum mechanics. Our research has a broad impact on chemistry, biology, material science, and environmental science.”

Berrah was also previously elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She earned a Davisson-Germer award from the American Physical Society and is a fellow of the American Physical Society.

She has also been an advocate for increasing the participation and retention of women in physics.

“I realized as an undergraduate student that there were just very few women, whether they’re undergraduate or graduate students, and it doesn’t make sense to me, because we all have a brain, and if we have an interest in physics, then we should pursue it,” says Berrah. “It’s a man-dominated field. And way back, women were not welcomed in physics.”

Over the course of her career, Berrah has worked to help women feel less isolated in the field, including serving as the chair of APS’ Committee on the Status of Women in Physics.

Berrah is currently chairing a committee in the physics department to organize a conference for undergraduate women and gender minorities in physics, that she says will occur January 24-26, 2025. She says it is an opportunity to help undergraduate women network and peer mentor with each other, so they don’t feel isolated, since they are often the only women in their classrooms.

The conference is a chance for women to learn together and become comfortable in the field, Berrah says.

“It’s important to mentor the next generation of women physicists and increase significantly their number,” says Berrah.