When it rains, it pours.

And for the last couple of years, it’s poured a lot in Connecticut.

The state experienced its third wettest year on record in 2023, accumulating nearly 65 inches of rain in the Hartford area – about 17 inches above the annual average. In developed locales, like on the UConn Storrs campus, all of that rainwater has to go somewhere.

That somewhere is typically an engineered stormwater system – something most undergraduate students don’t often think much about.

“I did not know a lot about stormwater management,” says Indigo Irwin ’25 (CLAS), an anthropology major from Hamden and an honors student graduating this coming December, “and now I’m writing a whole thesis about it.”

Irwin had also never installed drainage pipes, designed an infrastructure improvement plan, or worked within an administration to advocate for and implement a project. Neither had Trevor Donahue ’25 (CLAS), Rowan Solomon ’26 (CLAS), or Amanda Stowe ’26 (CAHNR) – the four undergraduate students didn’t even know each other before the fall 2023 semester.

But they each signed up for a unique anthropology and environmental studies course that combines intense classroom work with hands-on service learning.

Through that course, the four students joined together as a team to conceptualize and create a new stormwater management feature that’s active and highly visible on the Storrs Campus today: a rain garden.

Going Beyond Theory

A high-level, honors, service-learning course – that also allows undergraduate students to fulfill their general education environmental literacy, or “E,” requirement – Anthropology 3340 offers students a theoretical deep-dive on human-environmental interaction, ethics, climate change, disasters, environmental justice, and health.

But it also includes an applied aspect, where students engage with the broader campus community to try to implement some of what they are learning – to educate, to advocate, or to take environmental action.

“Its title is ‘Culture and Conservation,’ but the course very much is rooted in environmental anthropology,” says Eleanor Shoreman-Ouimet, an assistant professor anthropology who teaches the course. “Environmental anthropology, by nature, is very applied – it goes beyond simply the theory of human engagement with the environment toward really addressing how we can take the skill set of understanding human motivation and relationships with the environment to actually solve some of the wicked problems that are plaguing society today, plaguing the environment, plaguing non-human species, plaguing Indigenous communities around the world.”

The course alternates between theory weeks and applied weeks. In the theory weeks, students in the class come prepared to discuss topics involving high-level environmental anthropology issues, field work, and ethnography.

During the applied weeks, they start by brainstorming the kinds of projects they might like to work on – the scale and scope of which can vary greatly – before starting to sort themselves into groups based on individual interests and skills.

“All of the projects this semester were really remarkable in the sense that they were driven by activism and they were solutions-oriented,” says Shoreman-Ouimet, “but they were also lodged in respect for the campus, for the students, and even for the administration, and for wanting to figure out ways that they could contribute to the long-term health and sustainability of the campus.”

Through the brainstorming process, the students involved in the rain garden project all initially found that they had an overlapping goal of learning more about water management and green infrastructure on campus.

“There were people talking about how we could make the grass at UConn more eco-friendly, or use less pesticides, researching what is already done,” says Solomon, a chemistry major from Groton/New London. “We had some people talking about how we replace grass with other things. And then, we had people talking about stormwater management and looking at what kinds of projects had been done before.”

“We knew that we wanted to address storm water management on campus, and then also introduce more native plants,” says Stowe, who is from Newtown and is an environmental sciences major at UConn. “Building a rain garden would be the perfect way to do that.”

A Natural Fit

Rain gardens are shallow depressions in a landscape that typically include plants and a layer of mulch or ground cover. They can be built in either residential or commercial settings, where they’re typically larger and have an engineered design.

Regardless of the setting, rain gardens serve multiple functions in the areas where they’re installed.

“In basic terms, rain gardens are short circuiting the flow of water to limit pesticide drift,” says Donahue, an anthropology and environmental studies double major from Franklin, Massachusetts. “It’s essentially a collection of native plants that work well together, that can be pretty deep rooted.”

“And it helps reduce the storm flow, so that it’s not an excessive flow of water,” says Stowe. “Because obviously, that disrupts natural systems.”

Instead of directing that storm flow into stormwater systems, the water is sequestered into the landscape depression where its then slowly taken up and filtered by the plants growing in the garden.

“Since we’re getting so much excessive rain nowadays, we have to address more flooding issues,” Donahue says, “and that is another aspect.”

“One of the great things about rain gardens is that most are designed to be a natural depression in the ground, so it becomes a natural collection space,” Solomon says. “If they’re designed and placed well, all of that extra flooding water from how heavy the rain we get here can be will collect in that space, instead of collecting where you’re trying to walk or causing other problems.”

There are green stormwater features all over the Storrs campus, if you know where to look. Rain gardens, bioretention basins, and other infrastructure improvements have been strategically placed in areas where they can help reduce runoff, erosion, and the introduction of pollutants into local waterways.

“Very simply, we’re trying to mimic how this ecosystem functioned, the forest functioned, before this site was developed,” says Michael Dietz ’94 (CLAS) ’01 MS ’05 Ph.D., a water resources extension educator with the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment and director of the Connecticut Institute of Water Resources. “UConn is like a city, and these things are going in all over the country in our suburban and our urban areas, trying to help reduce the impacts of stormwater runoff from all these various surfaces and sidewalks and parking lots.”

In his role at UConn, Dietz works alongside UConn’s Facilities Operations and University Planning, Design and Construction to help install and maintain a number of green stormwater management features on campus.

“We’ve actually gotten some grants to install some of the things that are around campus that you’ll notice, some of the green stormwater features,” says Dietz. “The University has done a lot of this on their own.”

Answering Questions

Part of what Shoreman-Ouimet teaches students in her course is to start by asking questions.

“You can’t assume that a problem exists until you actually have the background knowledge to ask the questions and find out what other work is underway,” says Shoreman-Ouimet, “and I encourage them to find the people who are responsible for or working in the areas that they’re interested in studying. Ask the questions, interview them, and respect them. Do not assume for a moment that there’s something nefarious underway or something that’s lacking.”

That’s where the team from her class began – and they asked a lot of people a lot of questions.

In the fall 2023 semester, they created and launched an online survey where they asked fellow UConn students for their opinions on what the University was already doing in the areas of water and grass management. They asked how students used outdoor spaces and what kinds of things they would like to see changed.

In a short amount of time, they amassed more than 300 responses.

“It was more of that ethnographic component, because it is an anthropology class and we really needed that,” says Irwin. “But obviously, it’s great to see student input on what’s beneficial. And I found out that a lot of people didn’t really know what a rain garden was.”

“If you’re going to try to motivate a change on a college campus – if you’re going to try to motivate any change – it really helps to have numbers behind you,” says Shoreman-Ouimet. “They formulated a survey to demonstrate that what they were proposing to do had real value to students. They were able to then present that to the administration and say: People want this, they want to see this. Students value this. Students value environmental conservation. They value the aesthetic and the true environmental conservation efforts by the University.”

With numbers behind them, the team was ready to ask more questions, and Stowe reached out to Dietz with their idea for a rain garden.

“He was really interested in it,” Stowe says. “We did a campus walk with him where we walked around different parts of campus, and he showed us places where there already were rain garden installation-type projects. And then he took us to the Dairy Bar, because that was a site he had identified. He was like, I think this would be great for a rain garden.”

That particular site – right next to the Dairy Bar and behind the Agricultural Biotechnology Laboratory, in clear view of a row of picnic tables – is well suited to the kind of project the students envisioned for a number of reasons, Dietz explained.

“It was a really nice retrofit opportunity, because it already had a natural bowl, and the pipes, the building’s downspouts, were easily accessible, and it had a place for the overflow to go,” he says. “Plus, we had the visibility for educational purposes. So, they loved that idea. I loved it, and we just tried to transmit that love up the chain as we progressed in the discussions.”

With Dietz’s help, the team approached the administration with their idea.

“Mike initially came to me, because we had looked at that area in the past for a rain garden,” says Eileen McHugh, a senior project manager, landscape architect, and tree warden with University Planning, Design and Construction. “He wanted to disconnect some of the downspouts, and there was a low spot there.”

McHugh worked with the students to create a comprehensive plan for the site, which takes up about 250 square feet of space and was covered with turf.

“Of course, I work in plans all the time,” McHugh says. “They have their own ways of putting together plans – they take a picture, they draw on it, or they take an aerial and they draw on it. But it gets the idea across. And then, we had them stake it out. We met on-site, and we talked about how many plants were needed, and we talked about making sure we had enough coverage, so that it wasn’t too much mulch and so that it looked complete on day one.”

The plan also had to detail how the site would be laid out, which varieties of plants would be placed in the garden, who would be responsible for taking care of the garden until it was established, and how it would be funded.

“I think it was a little intimidating at first,” says Stowe, “but I feel like, because we were working together, it wasn’t as bad. Plus, Eileen and Mike helped guide us through it. So, it wasn’t like we were bouncing questions off the wall. They were there to help answer questions that we had.”

The team received administration approval to move forward with their rain garden project in November, right around Thanksgiving break – and just before applications were due to the Office of Undergraduate Research for Change Grants.

Born out of the UConn Co-op’s commitment to public engagement, innovative entrepreneurship, social impact, and active mentorship, the UConn Co-op Legacy Fellowship – Change Grants provide undergraduates the opportunity to engage in projects that make an impact.

UConn undergraduates in all majors can apply for up to $2,000 in funding to support community service, research, advocacy, or social innovation projects. Projects need to be student-designed or student-led, and applications are accepted from individuals and from small groups who will be working collaboratively or co-leading an initiative.

Irwin, Stowe, and Donahue applied for a Change Grant to financially support the project last year – they received their approval over winter break.

“This project represents what the UConn Co-op Legacy Fellowship – Change Grant is all about,” says Melissa Berkey, assistant director of the Office of Undergraduate Research, “supporting student efforts to make an impact on topics, problems, or issues that matter to them and expressing the core values of innovation, leadership, and service.”

“It’s been very helpful to work with Melissa from the Change Grant, and make sure that we’re following every protocol that UConn has, that we’re following the steps that we need to take,” Irwin says. “And then, obviously, we got funding from it, and we needed both approval and funding to actually make things happen, which has been great.”

They also devised a plan for the longer-term maintenance of the garden, a critical component according to McHugh.

“We have to be careful because, even though eventually these landscape details take less time to maintain, initially they don’t, and that’s a burden to our Facilities group,” she says. “Often with our projects, we will ask for two years of maintenance so that we don’t turn it over to our Facilities groups until it’s established and needs less time to take care of.”

“I’m the secretary of the Soil and Water Conservation Society,” says Stowe. “We’re planning on having that club do the maintenance for it, and then hopefully I can establish it so that by the time I leave, it’s a continuous thing every year.”

Pipes and Plants

With approval and funding, the team was finally ready to begin installing their garden once freezing temperatures began to subside during the spring semester.

They started by disconnecting the gutter downspouts from the nearby building, digging trenches, and installing new drainage pipes that now guide runoff from the building’s roof directly into the garden, instead of into the stormwater system.

Dietz arranged for turf to be removed from the area, and then the students worked to spread new soil in preparation for the plantings and placed river rock where the pipes stream into the garden.

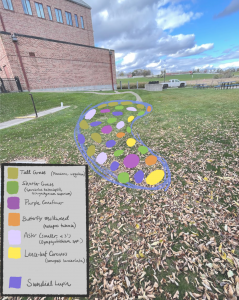

In late April, their carefully selected plants were delivered from a local wholesale nursery, Prides Corner Farms in Lebanon – native varieties like cone flowers, butterfly weed, little bluestem, and various native grasses.

“They were so helpful,” says Irwin. “We got all of our plants from them – like 140 gallons of plants. It’s just a whole lot, and it was really helpful to speak with them. We had to pick specific varieties for every plant, and they sent me email after email to help narrow it down.”

The plant choices were in line with recommendations for rain garden installations, Dietz explained.

“They chose species that were native to this area,” he says, “so that once they’re established, they’re not going to need a lot of extra water or fertilizer.”

“Most of them have flowers that are known to be really popular with pollinators,” says Solomon. “Most of them are also either host plants for various butterflies and moths, they’re host plants for caterpillars, or they produce seed heads that birds and small rodents will eat through the winter. We really wanted to maximize the benefits that this small area could produce, so getting plants that have multiple functions was the goal.”

On a warm Friday in late April, a slew of volunteers met the team at the site to help place the plants into the ground based on a grid system that Solomon drew up, and to then mulch the area.

Soon, signage will also be installed in the area explaining what the garden is and how it works.

“We’ve done some other signage for some of the green stormwater features on campus, and we kept it really small and concise, because we just figured people are walking by and weren’t stopping, but this is a different spot,” says Dietz. “We get a lot of people from outside the University coming in here, and we really want to use it as a good teaching opportunity.”

Lessons Abound

Once established, the new rain garden will help sequester about 60,000 gallons of stormwater a year from the roof of the neighboring building.

It’s a small improvement in the grand scheme of a campus as large as UConn Storrs, or in a state the size of Connecticut, or in a country as big as the United States.

But that’s part of what Shoreman-Ouimet hopes her students will learn from the class – to start by thinking locally.

“Start where you see yourself and tend your own garden, and then expand as you’re able,” says Shoreman-Ouimet. “These students saw what they wanted to do, and they saw spaces where assistance was needed and where a rain garden could make a tremendous difference in terms of water conservation.”

She adds, “The fact that they were able to build the proposal, have the proposal accepted by the administration, and then get funding before the end of a semester is just unheard of. It was pretty spectacular.”

For the students, the project offered lessons far beyond the actual installation itself.

“This helped me tailor my honors thesis,” says Irwin, who says the project helped steer her more toward a future in sustainable and environmental anthropology. “I want to talk about stormwater management and green infrastructure, so it’s been immensely helpful that I actually got to physically create something. Now, let me explore this on a global scale, and also on a local scale, and hopefully write about that in-depth.”

Solomon says that the project helped them see how group projects could be a truly positive and collaborative learning experience.

“How wonderful it can be when you find the right people to work with, who really complement everybody’s different skills and abilities, of how well that can go,” they say. “I love that I could just step in and do what I was good at and that was enough.”

For Donahue, the project was a lesson on the power of collective action.

“You really can make a change and you can make an impact in where you live and what surrounds you,” he says. “You’re not going to be able to do it on your own. But when you work with others, you can make an impact that can be seen, and it can actually be calculated. We can see how much runoff we have mitigated, and that’s something that’s super cool.”

Stowe hopes that the team’s work can be a model for other students who want to take action and implement change on campus.

“UConn is such a big campus, there’s so many opportunities,” she says. “I think just finding all the different people on campus who are passionate about these sorts of projects, and then working with them to actually have this come to fruition, is really cool.”

It’s those experiences, says Dietz, that inspire him to continue doing all he can to support student-driven work and educational opportunities.

“This is really what it’s about – the students learning an actual real-world thing that they can put their hands on, something that they can remember, and they can bring their families here and show them,” he says. “To me, that’s really a true benefit.”

For more information about green stormwater infrastructure at UConn, or for guidance on building a rain garden of your own, visit UConn’s Center for Land Use Education and Research NEMO Program website at nemo.uconn.edu.

For more information about UConn Co-op Legacy Fellowship – Change Grants, and other student funding opportunities available through the Office of Undergraduate Research, visit ugradresearch.uconn.edu.