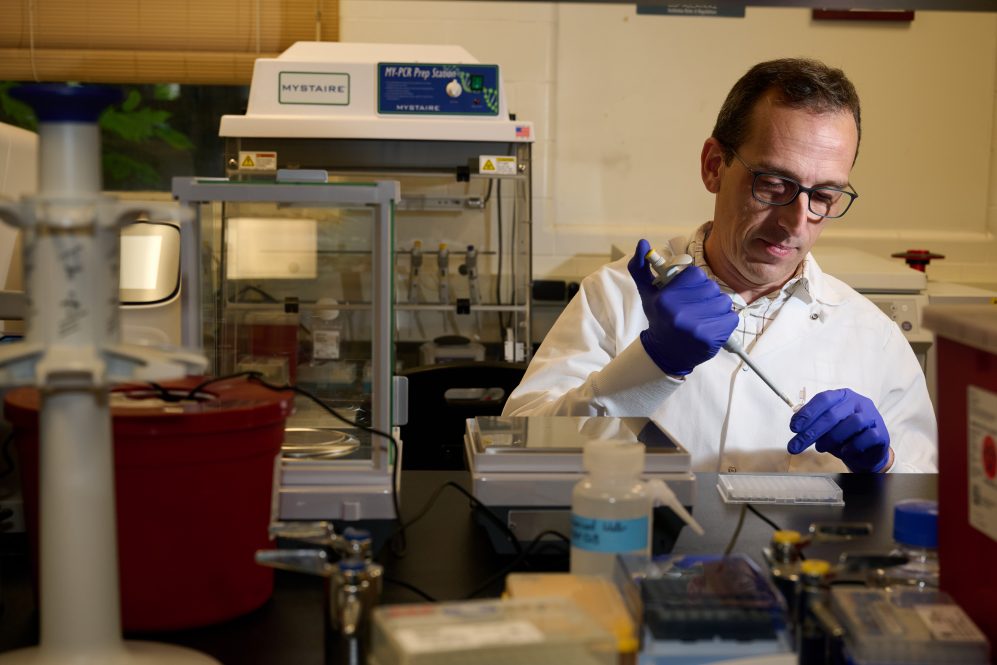

Assistant Professor Elsio Wunder has been awarded a $3.8 million R01 grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This grant will support Wunder and his collaborators in developing universal vaccine candidates for leptospirosis, an animal-borne disease which causes serious illness and an estimated 60,000 annual deaths worldwide.

Wunder teaches in the Department of Pathobiology and Veterinary Science in the UConn College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources (CAHNR), where he leverages his background in both veterinary medicine and human public health to research zoonotic diseases. Improving diagnostic and prevention mechanisms for leptospirosis has been the chief focus of Wunder’s research career.

There is currently no worldwide approved vaccine for leptospirosis in humans. It is considered a “neglected disease,” because it typically impacts poorer communities and individuals who lack access to adequate sanitation. Overall, neglected diseases do not receive the same attention or funding as diseases which impact more powerful groups.

Dedicated researchers like Wunder are working tirelessly to help correct this public health injustice. Now, with the help of this major award, they are one step closer.

“It is a big investment from the NIH,” says Wunder. “I’m very grateful. The fact that you have this major investment in a neglected disease is a really big step.”

Wunder is collaborating with researchers from Yale University; the University of California-Irvine; and Serimmune, an immune intelligence company located in southern California. In addition to Wunder (the project’s principal investigator), the full research team includes co-investigators Jun Liu (Yale), Philip Felgner (UC Irvine), David Huw Davies (UC Irvine), Li Liang (UC Irvine), Jon Shon (Serimmune), and Kathy Kamath (Serimmune).

Together, the team brings strong and diverse expertise across the fields of pathobiology, immunology, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), and vaccine development. They will spend the next five years developing vaccine candidates and testing them in animal models. At the conclusion of the five-year grant, they hope to have developed a viable vaccine candidate that is ready to be tested in human clinical trials.

A key goal for the project is to develop a universal leptospirosis vaccine, says Wunder.

“Then you have one vaccine that can be used in any epidemiological setting in the world, and it can protect people against leptospirosis, no matter which strain is circulating in the area,” he says.

This is no small task, as little is understood about leptospirosis causing illness. Wunder is one of just a handful of researchers worldwide focusing on this very issue.

Wunder has previously worked on an attenuated leptospirosis vaccine, which uses an inactivated form of the Leptospira bacteria to produce an immune response. This type of vaccine works like a flu shot, which uses an attenuated form of the influenza virus.

Although attenuated vaccines against leptospirosis have their own limitations for use in humans and animals – they tend to produce immune responses for specific strains of the bacteria, rather than the multiple variants that may be circulating in an area — this research paved the way for this grant.

Results from the attenuated vaccine showed that proteins of the Leptospira bacteria are important to protect against the disease. This research generated a list of potential new vaccine candidates to be evaluated.

With this new grant, Wunder and his team are working to develop a multi-recombinant protein vaccine – an immunization that works by using engineered proteins, rather than the bacteria itself, to elicit an immune response.

“All attempts [to develop a human leptospirosis vaccine] so far have failed, because it’s very hard,” Wunder says. “Bacteria have so many tools to evade host immune defenses – it’s hard to find that one protein that will lead to the broad immune response we want. So what we’ve done in our research is, instead of trying to just use one protein, try to use several proteins at the same time.”

The end goal is to create a vaccine using only small and relevant portions of those recombinant proteins (epitopes), ensuring the inoculation can be produced and distributed cheaply, since it needs to reach people in developing countries where leptospirosis is a major public health issue.

In the meantime, Wunder is continuing other leptospirosis research and teaching in CAHNR, where he helps students learn how to apply scientific knowledge to develop life-saving products.

“I teach a class that’s an introduction to pathobiology and a mix of basic and translational research,” Wunder says, “and how important translational research is to improve life for people – in terms of vaccines, treatments, diagnostics. But in order to have translational research, you do need basic science. And this grant is very much a mix of both.”