The Mediterranean island of Sicily has long been a crossroads of different cultures and societies, and now a team of scientists that includes UConn faculty and students is working to answer some questions about its earliest inhabitants. Namely: when did people first arrive, and what happened when they did?

The project is led by Ilaria Patania from Washington University, with UConn Department of Anthropology Department Head and Professor Christian Tryon, graduate students Iris Querenet Onfroy de Breville, Nicholas Gonzalez, and Peyton Carroll, and alum Danielle Falci ’23 (CLAS) partnering with other project members to help in the effort. The research was made possible in part by grants from a Summer Research Initiative grant from the UConn College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and the Multidisciplinary Environmental Research Awards for Graduate Students program from UConn’s Center for Environmental Sciences and Engineering and the Institute for the Environment.

The question of when people arrived is a strange one, Tryon says, because current evidence points to human occupation happening relatively late, maybe 17,000 years ago. To archaeologists, this a bit of a surprise because people had trekked overland to difficult-to-access areas like Siberia 45,000 years ago, or used boats for repeated journeys across the open ocean to Australia between 65-45,000 years ago. So why was the largest Mediterranean island seemingly uninhabited at a time when it could be seen from mainland Europe?

Were these early people avoiding smaller islands because they seemed poor in food and other resources compared to the mainland? Or did they lack the means to access them, such as boats that could navigate the famously dangerous Straits of Messina? Or is the evidence now underwater, buried by the rising sea levels that have characterized the world since the last Ice Age? Tryon thinks it is unlikely that a lack of the appropriate boating technology was a barrier to early access, but given how little evidence there is overall, treats the idea of such a “late” occupation of the island as a hypothesis worth testing. Until now, Tryon says there have not been any major projects focused on answering this question.

“This project started when Ilaria and I were brainstorming ideas, and she mentioned that her grandfather had dug a rock shelter in her parent’s backyard in Sicily. Ilaria really drives the project, but I said, ‘Well, if you need a stone tool guy, give me a call,’” says Tryon.

The more they considered the idea, the more support they found for moving forward with it.

“One of the factors why so little research has been done on Ice Age archaeology is because of Sicily’s incredibly abundant and outstanding Greek, Roman, and Norman UNESCO World Heritage sites,” says Tryon. “By comparison, the broken stones and bones of a Paleolithic site have just not been seen as interesting a topic for investigation.”

However, the researchers are finding that people are in fact very excited about the earliest human history on Sicily.

Now with the Early Occupation of Sicily Project (EOS), the team is focused on the southeastern part of the island, where they are surveying a series of sites both on land and underwater, examining existing museum and private collections, and enlisting the help of citizen scientists to locate potential new areas to survey or sites to excavate.

“It’s a fun and very photogenic project. There are caves on the coast, caves you have to swim into, and volcanoes erupting in the background. It’s pretty over the top,” says Tryon.

Looking for sites submerged underwater isn’t straightforward. Sicily’s complicated geological history means that ancient shorelines and landscapes are tilted to varying degrees across the island, and estimating ancient sea level – and thus where people might have lived – isn’t straightforward.

A source of data to help with these calculations is tiny, quarter-sized holes on the inside wall of one of the caves. The holes are made by a type of burrowing mollusk that anchors itself to the rock slightly below the water line, making these holes a good approximation of sea level. The researchers are mapping where they find these holes to help track the rate of uplift the island has experienced over time.

The EOS team is also interested in the changing ecology of the island. During ice ages, when the sea level dropped, the island was periodically accessible to mainland Italy via a land bridge, providing an opportunity for animals of all kinds to settle in Sicily and even adjacent islands, says Tryon. When glaciers melted and flooded the oceans, sea levels rose and the land bridges were once again underwater, resulting in the isolation of animals on islands, particularly those that don’t swim well, something that can lead to distinctive evolutionary changes in animal communities. For instance, Sicily was once home to tiny elephants the size of dogs, as well as gigantic swans, and one of the questions the researchers hope to answer is whether humans played any role in the extinction of these species.

“Islands are often good case studies, or natural laboratories, because their physical boundaries are well-defined, and they can be treated more or less as like a controlled experiment,” Tryon says. “Around 20,000 years ago or so, sea level had dropped enough that people could walk across from mainland Italy to Sicily. It looks like it was probably in two phases, where at one point it was a swamp, so big animals got across, and at another point it was dry enough that little animals got across, too. Whenever some new animal or plant comes in, there’s a major ecological shift that often includes the extinction of existing species, but it’s unclear if the shifts happened in Sicily at the same time when people arrived or perhaps shortly before they showed up. This is why we need better archeological data and fossils to help us understand what ecological communities might have been like before and after people arrived.”

Typically, to get this baseline information, one approach is to take sediment samples from lakes, ponds, or swamps where researchers can analyze things like different kinds of pollen in the sediment to show what local vegetation would have been like. However, Sicily is very dry, so this technique hasn’t worked so far, Tryon says:

“When other teams drilled the few lakes that there are, it was clear they had dried up during the period in question. This meant that was no mud, pollen, or anything else was being deposited in these lakes, or if it had been there long ago, later erosion wore it away. Now we’re trying to see what other kinds of data might be out there.”

For her undergraduate thesis, Falci combed the literature to find all available information on what animals had been documented on Sicily from about 20,000 to 10,000 years ago. Tryon says though it made for an excellent thesis, there simply isn’t enough data available to conclude exactly when species went extinct or if humans played a part in those events. However, Falci’s work helped focus on what data needs to be collected for the bigger project.

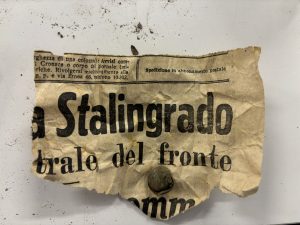

Querenet helped with surveying, and Gonzalez examined fossil animals and shells from museum collections, some of which hadn’t been studied in decades and were still wrapped in World War II-era newspapers. Carroll is doing her thesis on some of the stone artifacts from Sicily. As a first step, Tryon says, Carroll is focusing on studying a collection of tools from a site that was dug in the 1970s, examining how the tools were made and the materials they were made from, work which has yielded surprising insights into the people who made them.

“It turns out that when we first looked at the collection, based on how the tools were made, it didn’t look like these Ice Age people cared about conserving materials,” Tryon says. “For instance, they were throwing away tools they could have still used, so I thought they must be sitting right on the source of the good kinds of rock for toolmaking as the reason why they weren’t not being careful. When we later relocated the site and looked at the geology carefully, it became obvious that the rocks couldn’t be coming from nearby. People were clearly bringing this stuff in from somewhere, and it looks like the source of those rocks is probably at least 12 or 13 miles away up and over some pretty steep mountains, and that tells us something about how mobile these people were.”

Tryon says a unique aspect of the project is that Patania emphasizes outreach through public lectures and training to engage the public, get the word out, and even to enlist the aid of the Italian Navy, with many of their expert divers based in nearby Augusta. This approach seems to be working.

“Once we start digging a site, it’s exposed and at risk for vandalism or accidental damage. Unlike in Connecticut, where almost everything is privately owned, everyone has access to the beach in Italy. This means that coastal sites can be accessed by anyone, so getting the communities involved also has a practical side of things. It is important to give people a sense of ownership or involvement, and therefore to work together to preserve the sites that are part of their heritage.”

With the help of citizen science, the researchers are finding more sites than they ever could have on their own, a collaboration that has led to some unexpected finds. These include otherwise inaccessible cave systems on an Italian Navy base that were expanded into a tunnel network connecting pill boxes and bunkers during World War II.

“One cave in that system has a stalagmite that’s still dripping water. We’ve sampled that to see if that has been the case for 15,000 years or so. Even if not, stalagmites trap the water, pollen, and other materials and you can get all kinds of ancient and modern climate data from studying them,” Tryon says.

You can follow the project’s progress on the EOS Facebook page EOS instagram page or read more about in their article published this month in the journal PLoS One.