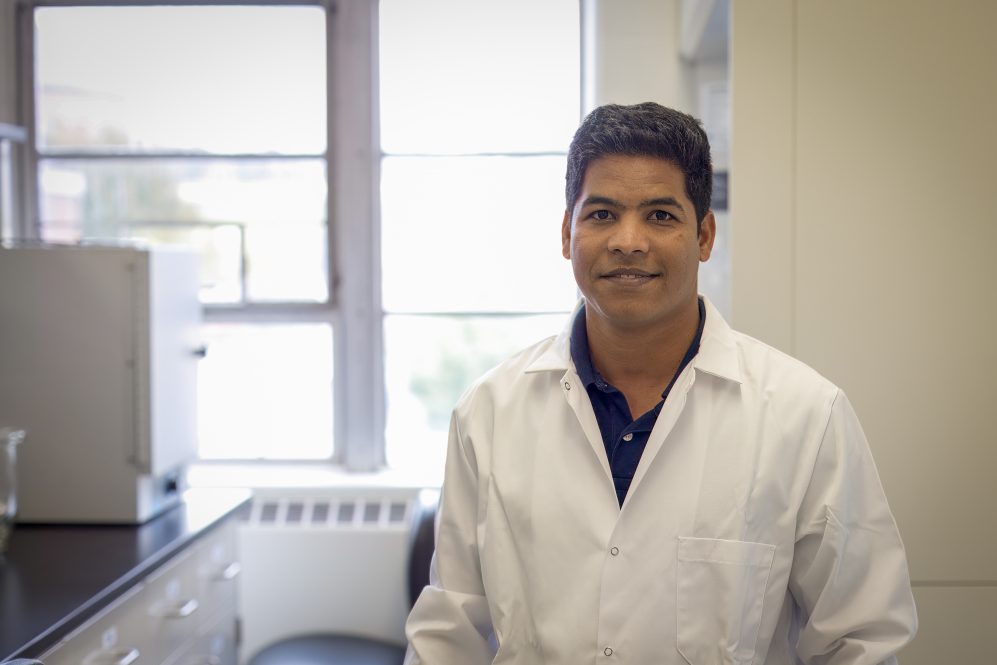

Elias Uddin, assistant professor of animal nutrition, is an expert in the field of ruminant nutrition and life cycle assessment. But he didn’t always plan to study animal science.

Uddin was raised on a family farm. But he wanted to pursue a career in human medicine. Over the course of his education, however, Uddin drifted back to his roots, studying animal science focusing on ruminants.

Ruminants are grazing herbivores, like cows or sheep, that have a unique form of digestion whereby they ferment their feed in a special compartment of their stomach called rumen prior to digestion thanks to microbes in their gut. This process allows ruminants to absorb nutrients from their feed. However, it also produces methane, a potent greenhouse gas, and emits through their respiration.

While agriculture only accounts for about 10% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., a whopping one third of methane emissions come from cattle. A single cow produces an average of 350-500 grams of methane per day depending on size of the cow and their feed composition.

Uddin’s research in the College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources (CAHNR) focuses on the interaction between ruminant nutrition and climate change. He is particularly focused on cattle because, while all ruminants produce methane, cows are by far the most common domesticated ruminant in the U.S.

Uddin studies how changes to the animals’ diets can reduce the amount of methane they produce. More fibrous diets have increased methane production. Swapping out some fibrous elements, like hay, for grain can reduce methane.

“You can switch the diet to change the substrate needed by the microbiome to produce methane,” Uddin says.

Changes to the animals’ diet, however, is a careful balancing act, Uddin explains. You can’t just take fiber out of the animals’ diet beyond a certain level as this can lead to serious health problems and even death.

Decreasing the amount of fiber in a cow’s diet can also change the fat percentage of the milk, which impacts the products farmers need to sell. Grain is also more expensive to produce, putting financial pressure on farmers while creating food-feed competition.

“A farm is a business,” Uddin says. “To survive in farming, you have to make your business profitable, and to do that you need to produce your final product in a cost-effective way.”

Enhancing Cattle Diets for Sustainability and Economics

Uddin also looks at feed additives that can reduce methane production.

“Yes, diet manipulation works,” Uddin says. “But we also have to think about other strategies like feed additive strategies that have been shown to be very effective and promising.”

One promising additive is Asparagopsis, a type of red seaweed, which contains a compound known as bromoform that inactivates an enzyme needed for methane production by the microbes in the rumen. However, this compound can also be hazardous to human health.

“You have to think about food safety for human beings and as well as safety for people who are involved with handling process of Asparagopsis,” Uddin says. “Because if a compound is coming through the animal system to the milk that means it’s going to come to your food system, and it might affect human health.”

Another issue is that the current infrastructure cannot produce enough Asparagopsis to even conduct an animal trial.

To address this, Uddin is collaborating with laboratories in Connecticut and in South Korea to identify more readily available alternative species as well as methods for scaling up Asparagopsis production.

Another limitation is that feed additives are currently very expensive. Without any kind of incentive, like a carbon credit, there is no financial benefit for farmers to adopt them.

Uddin is working to change this by combining feed additives to not only reduce methane emissions, but increase the cows’ productivity.

A very recent study published by Uddin’s lab demonstrated that adding isoacids to cattle feed can increase a cow’s milk yield by 2.5 kilograms per day while improving digestibility of nutrients depending on diet composition. Another article demonstrated that isoacids supplementation can also reduce enteric methane emissions under certain dietary conditions of the lactating cows.

“It will not only pay off feed additive costs, but also provide additional benefits,” Uddin says.

Carbon Footprint of Animal-Originated Products Using Life Cycle Assessment

Uddin’s research focuses on the whole lifecycle of a product. This approach measures the emissions produced by feed production, animal production, manure management, and fossil fuels used to power farm equipment to determine the carbon footprint of the product.

“What it does, mainly, is to acknowledge the whole life of a product, in this case milk,” Uddin says.

Uddin published several life cycle assessment study in the past and is currently working on a USDA-funded grant to incorporate economic measures into this life cycle assessment to better understand which environmentally friendly methods are most adoptable for farmers.

“We’re trying to understand the tradeoff between profitability and carbon footprint,” Uddin says. “If some farms are doing much better environmentally, their carbon footprint is lower, are they also making more profits? If that is the case that means they are engaging in some best practices so our next step would be to identify those so they can be disseminated to others.”

The overarching goal of Uddin’s work is to make agriculture more sustainable, both environmentally and economically as with a growing global population, the demand for food is also growing.

“There’s no single silver bullet,” Uddin says. “So, you have to find multiple options that work alongside one another.”