Like a poison pen, dying cells prick their neighbors with a lethal message. This may worsen sepsis, Vijay Rathinam and colleagues in the UConn School of Medicine report in the Jan. 23 issue of Cell. Their findings could lead to a new understanding of this dangerous illness.

Sepsis is one of the most frequent causes of death worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), killing 11 million people each year. It’s characterized by runaway inflammation, usually sparked by an infection. It can lead to shock, multiple organ failure, and death if treatment is not rapid enough or effective.

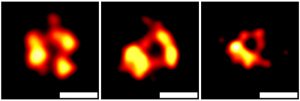

(Image courtesy of Shirin Kappelhoff, Eleonora G. Margheriti and Katia Cosentino / Osnabrück University, Germany).

But recent research has shown that it isn’t actually the infection that causes the spiraling inflammation: it’s the cells caught up in it. Even if those cells aren’t infected, they act as if they are, and die. As they die, they send out messages to other cells. Those messages somehow cause the recipient cells to die. If scientists understood what caused this deadly message chain, they might be able to stop it. And that could help heal sepsis.

The deadly message mystery may now be solved. It appears that the “messages” are a byproduct of the cells trying to stay alive, UConn School of Medicine researchers report in Cell.

The process starts with cells that really are infected. To prevent the infection from spreading, those cells destroy themselves by sending a protein called gasdermin-D to their surface. Several gasdermin-D proteins will link together to create a round pore on the cell, like a hole punched in a balloon. The cell’s contents leak out, the cell collapses, and dies.

But the collapse isn’t inevitable. Sometimes cells can act quickly and eject the section of their surface membrane with the gasdermin-D pore. The cell then zips the membrane closed and survives. The ejected membrane forms a little bubble, called a vesicle, that just happens to carry the deadly gasdermin-D pore. The vesicle floats around, and when it encounters a cell nearby, that deadly gasdermin-D pore punches into the healthy nearby cell’s membrane and causes that cell to spill and die.

“When a dying cell releases these vesicles, they can transplant these pores to a neighboring cell’s surface, which leads to the neighboring cell’s death,” says Vijay Rathinam, an immunologist in the UConn School of Medicine. In other words, the deadly messages are a side effect of cells just trying to save themselves. A group of dying cells can release enough gasdermin-D vesicles to kill a considerable number of nearby cells. That spreading message of death fuels the spiraling inflammation of sepsis.

Rathinam and his colleagues are now looking for a way to damp down the deadly gasdermin-D vesicles. If successful, it could lead to a treatment for inflammatory diseases like sepsis.

This study led by Skylar Wright, an MD/PhD student in the Rathinam lab, was done in collaboration with the laboratories of Drs. Jianbin Ruan, Beiyan Zhou, Sivapriya Kailasan Vanaja of UConn Health and Dr. Katia Cosentino of University of Osnabrück, Germany. This project was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health to Dr. Rathinam.