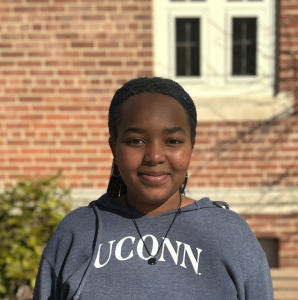

Kanny Salike ’26 (CLAS) didn’t grow up in the Deaf community and no one around her uses American Sign Language – she didn’t even know her A, B, Cs until just over a year ago.

The linguistics and anthropology double major says she developed an interest in learning ASL after thumbing through a sign language dictionary gifted by her mother. The handshapes were intriguing and the idea of using facial expressions to communicate was fascinating.

“I’ve always been interested in languages and wish I knew more. But learning about how language changes over time and how our society can influence those changes is most interesting to me,” she says.

Salike took Elementary American Sign Language I in fall 2023, then followed up with the second level in spring 2024. This year, with an undergraduate research fellowship from the UConn Humanities Institute, she’s independently discovering “The Evolution of African American English (AAE) and Black American Sign Language (BASL) in the United States.”

It was in one of those early ASL classes that Salike says she learned there was even such a thing as BASL and that its origin parallels the evolution of AAE, each becoming distinct dialects with roots in ASL and Standard American English (SAE), respectively.

That got her thinking: Does racism and audism impact the way language evolves and the way people freely speak or sign? Does racism exist in the Deaf community? Does being deaf and Black influence how people are treated in a hearing-centric world? Do AAE and BASL share historical similarities in the way they became their own languages?

“It’s important to unpack how systemic structures influence the way people live,” she says, “and having more literature out there on this could start to break down the racism and audism that still exists.”

When speakers of SAE hear someone conversing in AAE, or vice versa, Salike says, they take notice of the grammar differences. AAE uses certain constructions including double negatives, for example.

“People have this idea that African American English is not a proper way to speak English because they are using ideas of what Standard American English should sound like. But each is different unto its own,” she says.

The same is true for the differences between BASL and ASL, she continues: “There’s a common misconception that there is one universal sign language, but there’s the same diversity in signing as there are number of groups in the larger Deaf community. For instance, if someone from the East Coast were to sign with someone from the West Coast, just like with oral communication, there would be detectable accents.”

Salike says that for her one of the trickiest parts of learning sign language comes with its reliance on facial expressions to convey words, phrases, and sentiments, in addition to the use of hand gestures.

That’s only amplified in BASL, which is even heavier on facial expressions and utilizes two-handed gestures more frequently.

While she says she can’t put a timestamp on precisely when BASL developed, it came about during segregation when white students were educated separately from Black students, a separation that allowed BASL to flourish.

“For a long time, manual languages were banned in white schools. You weren’t allowed to teach deaf children how to sign. They would need to learn to speak or use oral language as well,” Salike explains. “But the rules were different in Black schools where Black children had a space to learn sign language and practice signing because their education wasn’t given the same attention as white students.”

In the same way that SAE and AAE are mutually intelligible, so is ASL and BASL, she adds, noting that nonetheless there would be some fits and starts in communication, much like there are when two people with distinct regional dialects communicate (for example, the difference between the use of the word “soda” in the Northeast and “pop” in the Midwest).

Sign language is not a word-for-word translation, just as converting English to Spanish isn’t and often depends on context. That’s why sign language interpreters are not called translators, Salike says. Their job is to convey the essence of what the person is trying to say.

As Salike spends the rest of the semester pouring through the research around BASL and AAE, she also is seeking to talk with a few deaf people from the Black community to survey their experiences and compare them to the findings of noted researcher Carolyn McCaskill, a Gallaudet University professor who’s been honored for her research on ASL in the Black Deaf community.

“Language is powerful and people who speak AAE or sign BASL often get discriminated against just because they don’t communicate in the standard dialect,” Salike says. “We need to create a more inclusive environment for everyone to communicate freely no matter their origins or their background.”