Fourteen minutes ago, the nonprofit advocacy group Children’s Cancer Cause posted on the social media app X that members were on Capitol Hill asking Congress for funding to fight #childhoodcancer.

Three days ago, a special education teacher from Texas posted about a young girl, Caitlyn, who twice survived #childhoodcancer, along with a difficult bone marrow transplant. She included a link to the girl’s GoFundMe account.

Seventeen hours ago, the chairman and CEO of a cancer response team sought prayers for Kellan, who’s in a battle with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and by virtue of his courage is heralded a “#childhoodcancer warrior.”

These are just three posts from a search of the hashtag on X (formerly Twitter) in late February, a snapshot of the thousands – many, many thousands – shared on the app over the years. A new study from UConn researchers looked at 1,000 posts from October to December 2022 to understand who’s leading the conversation about childhood cancer and what they’re saying.

“We found the largest number of tweets on childhood cancer were not from health care professionals, like oncologists. They were not from nonprofit organizations, like American Cancer Society. They were from individuals – parents, caregivers, and family members. These were the people actually doing the most in terms of raising awareness,” says Sherry Pagoto, allied health sciences professor and director of the UConn Center for mHealth & Social Media.

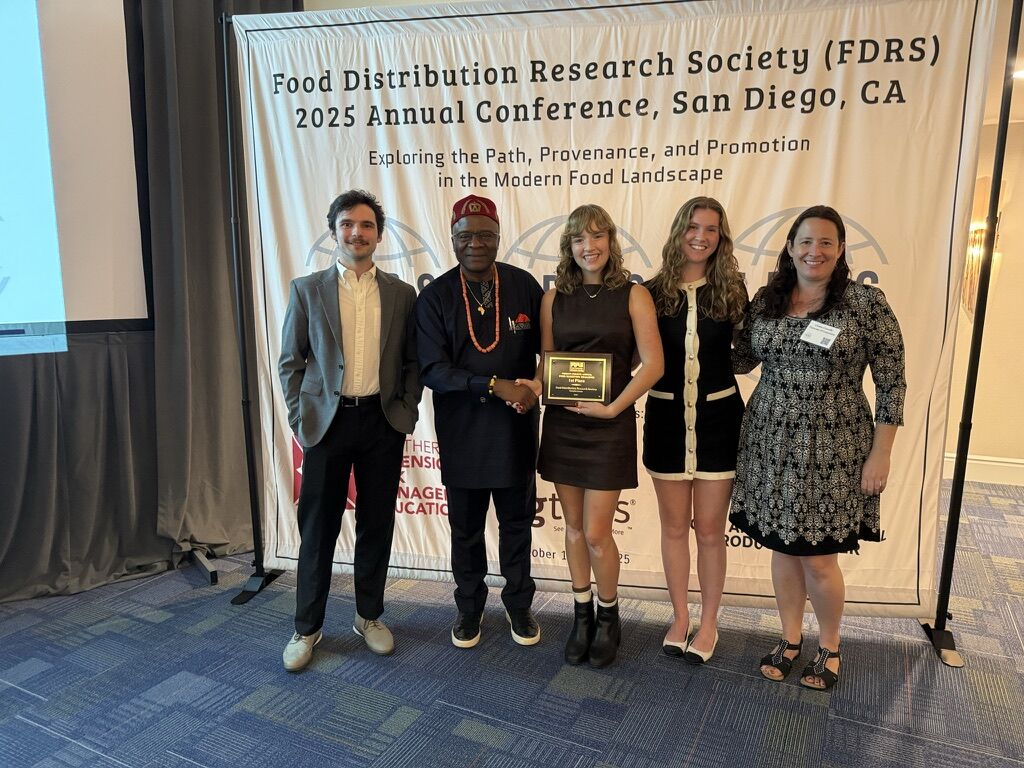

Pagoto and human development and family sciences professor Keith Bellizzi, along with four students from the high school, undergrad, and graduate levels, recently published, “A Content Analysis of #Childhoodcancer Chatter on X,” in the Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology.

They found that “educational” tweets and ones that discussed “science” accounted for a combined 28.1% of posts about childhood cancer. Next came “fundraising” with 21.2% of tweets – Twitter did not become X until mid-2023, after the study. “Advocacy” was most prominent in 20.2% of tweets, and “motivational” posts comprised 17.5%.

“Cancer disrupts lives, bringing uncertainty and hardship to individuals and their families,” Bellizzi says. “These findings highlight how different stakeholders may reclaim a sense of control in a situation that often feels uncontrollable. By turning to social media, they are not just sharing stories, they are actively shaping the conversation, raising funds, spreading awareness, and building a supportive community.”

The study says a total of 3,217 tweets were captured from that three-month period in late 2022 by searching on the hashtag, so researchers pared down the total and randomly selected 1,000 to review. They came from 454 unique accounts.

We can study all these different sources of data, but social media gives us a unique form of data by showing us how patients, caregivers, and health care professionals talk about health in their natural environment. — Professor Sherry Pagoto

Among those accounts, researchers found that family members of children with cancer accounted for most of the content on childhood cancer, making up 41.5% of the tweets that were reviewed. Nonprofit organizations were next at 38.6%, followed by health professionals at 8.7%, academic and/or medical centers at 4.2%, and for-profit companies at 3.5%.

“We can study human behavior in a lot of ways,” Pagoto says. “We can do surveys. We can do focus groups. We can take blood samples. We can study all these different sources of data, but social media gives us a unique form of data by showing us how patients, caregivers, and health care professionals talk about health in their natural environment.”

Cameron Cordaway ’23 (CLAS), who majored in physiology and neurobiology and worked on the study her last year at UConn, says she wasn’t surprised to find individuals sharing their stories, sometimes in great detail, on social media.

After all, sharing experiences with others in a digital way is second nature for her generation, she says.

“When I got into dental school, the first thing I did was text my whole family and post it on social media,” Cordaway says of her acceptance to the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, where she’ll begin studies this fall. “For my generation, our whole lives are on social media. It’s second nature when something happens in your life to tell people on your phone in some way.”

She continues, “Something as heavy as a cancer diagnosis, while it might not be the first thing you would post in public, people definitely would use social media to communicate, inform, and educate about it. It’s also a good way to let people know, ‘Hey, this is what’s going on with me. This is why I haven’t reached out or why I haven’t been as present.’”

Pagoto says she and Bellizzi conceived the project after noticing that a father chronicling his young son’s cancer journey on Twitter had become a trending topic on the site.

“It really enraptured Twitter users for months, as people watched from afar as this father shared his family’s journey through his child’s cancer treatment,” Pagoto says, explaining that got her thinking about how social media was being used among those thinking about, dealing with, and focused on childhood cancer.

She and Bellizzi turned to digital natives like Cordaway, Cindy Pan ’24 MPH, clinical psychology grad student Jessica Foy, and Andie Napolitano ’28 (CAHNR) who was a high school junior when she worked on the project.

Napolitano, who was a student at Amity Regional High School in Woodbridge, says the school offers a science research program that allows young teens in their sophomore year to start working with university-based researchers.

That year she worked with a professor from the University of New Haven, she says. The last two years of high school, though, were spent with Pagoto and Bellizzi.

She says she liked the idea of a research project dealing with social media and wanted to use the experience to test drive UConn as a potential for her undergraduate work. A bonus was that like the other students, she could be part of the project from start to finish.

Pagoto notes that many research studies take many years to complete, thus students see only a small piece during the year or two they’re on board.

Since tweets are in the public domain and searching Twitter back then was easy, data collection was almost effortless, and the four students could quickly get to work analyzing the tweets.

That’s the fun stuff, they say.

“I have an interest in social media research because people spend so much time on it and so many think it’s a bad thing and that only misinformation spreads online,” Napolitano says.

Doing a project that looks at its benefits especially appealed to her.

Pagato says that in addition to X, Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok also get heavy use from people using the platforms to talk about their other physical issues and even mental health problems.

“There are influencers with Tourette syndrome, depression, cancer, and any condition you can imagine, and, yes, while there is misinformation on social media, there’s also community on social media and these influencers are sharing their experiences and garnering support,” she explains.

“It’s a little like, ‘Here’s my experience. I have this diagnosis, and this is what my life is like,’” she continues. “Health influencers on social media destigmatize many disorders that have been hiding in the shadows, particularly mental health disorders.”

Those with similar diagnoses, she says, can learn from others about what to expect, how to cope with side effects, how to find clinical trials, and what questions to ask.

“Patients have a lot to say about their experience. They’re the ones who must live with the disease. Their voices matter. I wonder if that’s what draws them to social media – to be heard. Oftentimes, we’ll hear in studies that patients don’t feel heard by their doctors. They may not even feel heard by their family members,” Pagoto says.

Napolitano agrees.

“In today’s mainstream media environment, for a lot of reasons, stories don’t get heard. Social media is a way for people to make themselves be heard,” she says.

And that includes the mother of a son treated for neuroblastoma in 1999 who posted four hours ago in a conversation about bringing a newborn into a crowded airport that she had to protect her young son from viral exposures the first eight years of his life: “This is what having a child w/ #childhoodcancer or a #survivor with vulnerable health is like.”