2024 was the hottest year, within the hottest decade, since we have kept these records. How these consecutive, extreme heat years will impact the survival of species across the globe is an immense and pressing question that a team led by UConn researchers is working to answer. In their report published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS), they describe a tool they developed for rapid climate bioassessment, and how it could help prepare for deadly heatwaves and potentially prevent extinction for species most at risk.

UConn Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Professor and co-author Mark Urban says there is an urgent need to fill the gap and develop methods to evaluate risks to biodiversity, as current means are often years or decades behind and by the time effects are realized, it may be too late to intervene.

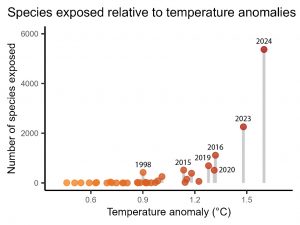

Urban partnered with lead author Assistant Research Professor Cory Merow and others to develop a tool to fill this gap that was not only fast, but could be applied to as many species as possible. The method assesses the outcomes of a species’ exposure to climate extremes and climate variation. Merow says they initially developed the method in 2023 to look at heat, and as 2024 proved to be even hotter, they immediately applied the format to a query of more than 33,000 vertebrate species worldwide in 2024.

“We are trying to hindcast or forecast species that were recently or are about to be at greater risk,” says Merow. “We might see some downstream impacts but we need targeted monitoring to determine what these impacts are to develop a mitigation plan. That’s the broader context that we’re hoping to provide.”

The researchers say this tool can help pinpoint species that have been exposed to unprecedented or abnormal conditions, and this wellness checkup of sorts can happen to see how they are faring.

This assessment analyzed the historical record across the range for each species, says Merow. For temperature, they noted the hottest year and whether or not 2024 was hotter. The process is computationally intensive but quantitatively, it is relatively simple.

“We can say for each species at each location in its range whether it has been exposed. Then we add it up over the whole range,” says Merow. “We could say 50% of the range has been exposed, or 3% of the range has been exposed. Then we stack up all the species that occur at a location and look at risks to entire communities. We determined the worst a species has seen and then asked whether 2024 was worse, and quite often, it was.”

Urban says they found that one in six species were exposed to unprecedented temperatures in 2024. 80% of the species exposed in 2023, which had previously been the hottest year on record, were also exposed in 2024.

“We entered this project thinking maybe it’s random across the world, one place gets hit one year and a different one gets hit another year. That’s not how it seems to work,” says Urban. “It seems to be the same species and regions are getting hit during these really hot years and that seems to compound over time, like a bad mortgage. We like to say there’s no rest for the wilted.”

They identified hotspots mostly clustered within equatorial South America and Africa. Urban explains that though they tested many hypotheses about exactly what drives these areas to be the hardest hit, there is no one smoking gun to explain the patterns.

“A surprising thing is that it’s not simply widespread across tropical locations. We’re not just saying in hot places, things are hot. It’s pretty specific,” says Merow.

Urban and Merow hope this raises concern in conservation circles because each event adds to the compound interest of weakening resilience and potentially leading to the decline of the species. They plan to up the game on this approach and expand to include annual reports for more species, including insects and plants, to incorporate more risk factors, and increase the precision of the analysis, but that takes a nuanced approach.

“It’s tricky, because all species respond to different things in unique ways. We want a risk assessment that’s both relevant for a wide variety of taxa with different needs but doesn’t require detailed life history knowledge across each species range, because that information doesn’t exist, and probably never will before it’s too late,” says Merow. “It’s a delicate balance.”

Urban says that ultimately, they hope to develop forecasts that can be used to direct resources on the ground for monitoring and preparing for extreme heat events, for example, by providing water, shelter, or food to prevent the worst effects.

“That’s what motivates us. 2024 was likely the hottest year in 100,000 years. Species have adapted to recent conditions, and maybe they can survive these novel conditions, or maybe they can’t, but we won’t know without checking, in a focused way,” says Urban.

Merow points out another important aspect of today’s climate change is that it is happening at a much faster pace than previous climatic changes, and this may impact responses that worked in the past, like adaptive evolution.

“We don’t know the impacts of the compounding years. Building on the mortgage interest idea, that’s also how populations change. If your bank account goes to zero, it doesn’t matter what your interest rate is,” says Merow. “When five out of the last 10 years are the worst that we’ve seen in recent history, it can have compounding effects on populations, and unfortunately, we’re doing the experiment to see how much they can tolerate.”