In our recurring 10 Questions series, the Neag School of Education catches up with students, alumni, faculty, and others throughout the year to offer a glimpse into their Neag School experience and their current career, research, or community activities.

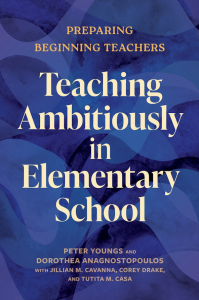

Dorothea Anagnostopoulos and Tutita Casa recently co-authored a new book with colleagues through Harvard Education Press, “Teaching Ambitiously in Elementary School: Preparing Beginning Teachers,” which promotes deep, conceptual learning at the elementary level through targeted assignments, tailored support, and skillful feedback.

Anagnostopoulos, professor of curriculum and instruction at the Neag School, previously served as associate dean for academic affairs and executive director of teacher education. Her research examines teaching quality, teacher education, and how accountability and reform affect teachers’ work and has been funded by the Spencer Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and The National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. In addition to “Teaching Ambitiously in Elementary School: Preparing Beginning Teachers,” her books include “The Infrastructure of Accountability: Data Use and the Transformation of American Education,” and “The Corona Chronicles,” which examined how COVID-19 reshaped life and education, highlighting leadership and the enduring power to inspire and build allyship through hardship. A former secondary English teacher, she previously taught at Michigan State University and served as vice president of the American Educational Research Association’s (AERA) Division K.

Casa, associate professor of curriculum and instruction at the Neag School, studies how classroom discourse can empower students to engage with mathematics as mathematicians do. Her research focuses on oral and written mathematical communication and its role in deepening understanding. Casa has led multiple National Science Foundation–funded projects, including Project M²: Mentoring Young Mathematicians and the Elementary Mathematical Writing Task Force, which developed resources to guide teachers in fostering meaningful mathematical writing in elementary classrooms. She co-edited the book, “Illuminating and Advancing the Path for Mathematical Writing Research,” which highlights the current state of writing to reason mathematically and proposes future research in this formative area of scholarship. She taught in elementary and middle school settings and has served in various leadership roles, including as editorial panel chair of Journal for Research in Mathematics Education and co-chair of AERA’s Division K, Section 1, Teaching and Teacher Education in the Content Areas.

In this feature, we learn how their new book helps ambitious teachers thrive when they first enter the profession.

Q: Five authors, one big topic — that’s no small feat. How did you come together to write “Teaching Ambitiously in Elementary School,” and what sparked your shared interest in this work?

A: The book draws on a research study that followed 125 preservice elementary teachers from five teacher preparation programs, from student teaching through their first years in the classroom. This included 80 beginning teachers we interviewed and observed teaching mathematics and English language arts (ELA) during their first and second years, as well as 16 teachers we followed into their third year. We wanted to understand how teacher education experiences, school resources, and teachers’ individual goals and beliefs shaped their development of ambitious instructional practices.

Working with colleagues at the University of Virginia and Michigan State University, we sought to answer whether and how university-based teacher education affects the quality of beginning teachers’ instruction. We focused on learning opportunities in teacher preparation that help novices enact instructional practices proven to support students’ deep understanding. We also examined how beginning teachers’ school contexts and personal beliefs influenced how they used what they learned in their programs.

Q: The phrase “ambitious teaching” is central to your book. How do you define it, and why is it especially important in today’s elementary classrooms?

A: Ambitious instruction engages students in making sense of academic tasks and developing disciplinary practices, such as comparing solution methods in math or considering an audience when writing. Teachers who teach ambitiously center students’ ideas and thinking while using scaffolds to help them deepen their learning.

This approach is especially important in elementary education. Research shows that effective elementary teachers positively affect students’ long-term academic and career outcomes. Preparing beginning teachers to teach ambitiously can improve student learning, particularly for those historically underserved due to economic inequality, racism, and other inequities.

Q: The team’s research included more than 1,000 hours of classroom observation. What stood out most?

A: Beginning teachers were able to develop some ambitious practices more easily than others. They improved their ability to engage students in rigorous learning tasks in both math and ELA, but struggled with what we call instructional scaffolding — modeling and teaching conceptual and procedural learning strategies.

Because scaffolding is vital to student learning, teacher educators and school leaders should focus more attention on helping novices build these skills through coursework and feedback, both before and after they enter the profession.

We also want to acknowledge Kylie Anglin, assistant professor in the Neag School’s Department of Educational Psychology, who played a key role in the analyses that revealed this insight.

Q: The team looked closely at teacher preparation programs. What are they getting right and where can they improve?

A: Teacher education has often been criticized as “incoherent,” offering disconnected learning experiences. The programs we studied, however, were adopting a practice-based model that centers coursework on a set of core teaching practices shown to support student learning. Across programs, preservice teachers reported that their coursework gave them a coherent vision of teaching on which to build their practice.

We found that coursework focused on general teaching methods and principles of instruction was especially helpful in teachers’ first year, providing a foundation for ambitious instruction in both math and ELA. Learning opportunities related to teaching diverse learners were particularly valuable in teachers’ second year — especially in math — as these teachers were more likely to model and teach conceptual and procedural strategies.

We found that coursework focused on general teaching methods and principles of instruction was especially helpful in teachers’ first year, providing a foundation for ambitious instruction in both math and ELA. — Dorothea Anagnostopoulos and Tutita Casa

Student teaching was another powerful factor. Opportunities to learn, practice, and receive feedback on ambitious instruction during student teaching were linked to stronger teaching early in teachers’ careers. These experiences were most effective when connected to university coursework. Beginning teachers who had these opportunities were more likely to take charge of their own professional development and even become resources for colleagues.

Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of strong partnerships between universities and schools, particularly around helping beginning teachers develop their skills in instructional scaffolding.

Q: Mentorship and support are recurring themes in your work. What makes mentoring effective for new teachers?

A: Beginning teachers must develop their practice while forming relationships with students, colleagues, administrators, and families — often while teaching multiple subjects. They need various supports, including emotional encouragement that builds confidence and resilience. Mentor teachers, principals, and colleagues play key roles in this.

New teachers also need practical support for building ambitious instructional practices. This includes access to high-quality curricula and guidance on engaging students in intellectually demanding tasks. Instructional coaches, who work directly with beginning teachers in classrooms, are especially effective. Grade-level teams can also be valuable when they move beyond sharing materials to jointly examining student data to inform instruction.

Importantly, some beginning teachers found they needed to distance themselves from colleagues who expressed deficit views of students or resisted ambitious instructional practices. Building ambitious teaching skills requires aligning with colleagues who believe in students’ capacity to learn.

Q: What advice would you offer to new teachers striving to teach ambitiously despite limited time or resources?

A: Teachers who taught most ambitiously shared a belief that all students are capable learners and that the knowledge students bring from their families and communities is a valuable resource. They viewed their own growth as teachers as intertwined with their students’ learning and focused on mastering a few key instructional practices that best fostered student engagement and understanding. This focus helped them direct their own professional learning and grow more confident in their teaching.

Teachers who taught most ambitiously shared a belief that all students are capable learners and that the knowledge students bring from their families and communities is a valuable resource. — Dorothea Anagnostopoulos and Tutita Casa

Q: With students bringing so many backgrounds, languages, and learning needs, how can teachers design ambitious instruction that works for everyone?

A: Ambitious instruction starts with valuing students’ ideas and experiences. It requires teachers to recognize and draw upon students’ diverse cultures, identities, and languages as critical resources for learning. Teachers who view diversity as an asset can design instruction that engages all students meaningfully.

Q: Your team studied both math and English language arts instruction. What did you learn from comparing the two subjects?

A: Beginning teachers’ development of ambitious practices was similar across subjects. In both math and ELA, they improved in creating rigorous lessons but struggled to model and teach conceptual and procedural strategies. This suggests teacher educators and school leaders should dedicate more time and resources to supporting teachers’ understanding and enactment of scaffolding practices.

Interestingly, we also found that teacher education learning opportunities tended to support ambitious teaching more in math than in ELA — an area that warrants further study.

Q: Teacher beliefs and values play a big role in practice. What helps teachers align their beliefs with ambitious teaching goals?

A: Ambitious teaching begins with believing all students can learn rich, meaningful content. Providing preservice teachers with opportunities to learn, practice, and get feedback on instructional strategies that center students’ ideas helps them sustain these beliefs and put them into action in their classrooms.

Q: Whether they’re educators, mentors, or policymakers, what lasting message do you hope “Teaching Ambitiously in Elementary School” leaves with them?

A: The transition from teacher preparation to the in-service years can establish long-term teaching practices that affect many students. Coordinating efforts among teacher educators, mentors, and policymakers can help novices implement ambitious teaching early in their careers. Elementary teachers who recognize shared pedagogical approaches across English language arts and mathematics, along with each discipline’s nuances, benefit even more.

To learn more about their book or work, email dorothea.anagnostopoulos@uconn.edu or tutita.casa@uconn.edu.