Scarring is a key feature of chronic kidney disease. Now, University of Connecticut researchers report in Kidney International that a specific protein encourages scar tissue formation. Their research could someday help preserve kidney function in people with the disease.

About one in seven American adults has chronic kidney disease, according the Centers for Disease Control. And the majority of them don’t know it. Medicare’s total cost to treat people with chronic and end-stage kidney disease in 2019 was $125 billion, and that number keeps going up.

Chronic kidney disease is caused by a spectrum of disorders that stress the kidneys over time, gradually causing scar tissue to build up. The scar tissue gradually replaces healthy kidney tissue. The more scarring in a kidney, the less able it is to do its job filtering the blood and balancing the body’s mineral levels. Eventually people with advanced kidney disease must go on dialysis or get a kidney transplant to survive. Preventing scarring from happening in the first place could help enormous numbers of people avoid dialysis and the burden of end-stage disease.

UConn School of Medicine nephrologist and scientist Yanlin Wang and colleagues were looking at how kidney scarring occurs. A protein called SOX4 caught their attention. SOX4 is involved in many of the processes that transform cells, both in normal development and in cancer. However, its role in the fibrotic transformation that leads to scar tissue formation is not known.

Wang and his colleagues looked at kidney tissue from both animal models of chronic kidney disease and human patients. They could see that the tubular epithelial cells that do the crucial work of filtering the blood would get stuck in a stressed state in diseased kidneys, and SOX4 seemed to involved. SOX4 interacted with other factors to reprogram these tubular epithelial cells and activate nearby scar-forming cells that create scar tissue.

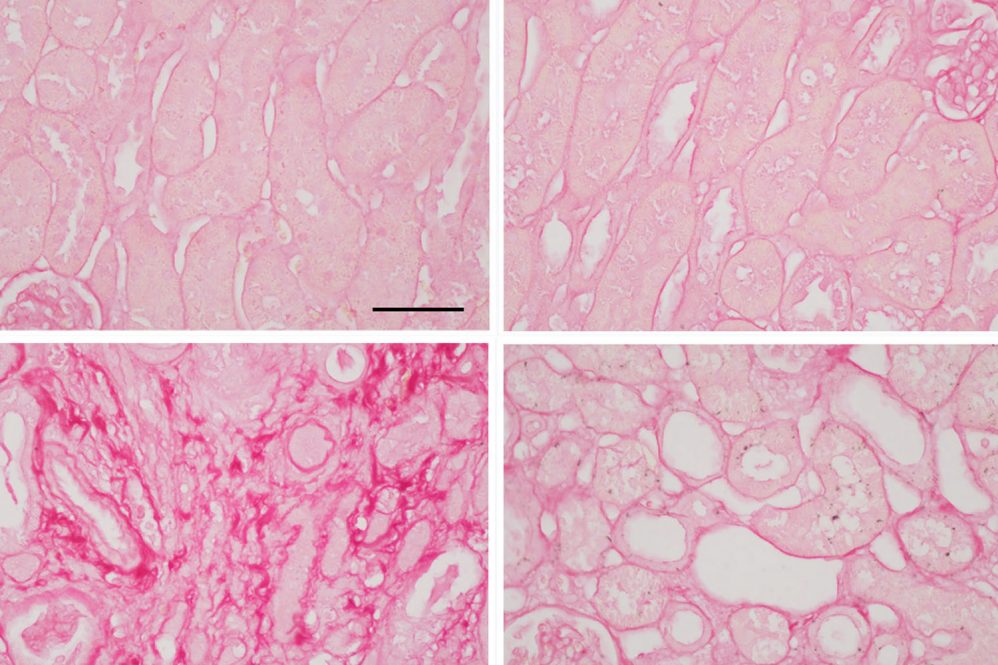

To test whether SOX4 was necessary for this scarring to occur, the researchers looked at mice that lacked SOX4.

“The result was striking: without SOX4, kidneys had far less scarring,” says Wang. SOX4 seemed to actively push stressed cells to form scar tissue. The Wang laboratory is investigating how SOX4 regulates these processes and is developing new therapeutic strategies targeting SOX4 for the treatment of chronic kidney disease.