“Race and Revolution: Still Separate – Still Unequal,” the third installment in a series of art exhibitions that call on history to expose repeated patterns of systemic racism in the United States, will be on display at the Stamford Campus through March 11.

My hope is that using art as a tool to access history can reach people in a way that words and protest have not. — Katie Fuller

The exhibit features works by nine artists and is mounted at locations throughout the Main Building. During the opening reception on Jan. 31, from 6 to 8 p.m., there will be a special performance by artist Dennis Redmoon Darkeem, whose work critiques social and political issues affecting U.S. and indigenous Native American culture.

“My hope is that using art as a tool to access history can reach people in a way that words and protest have not,” says Katie Fuller, co-curator for the exhibit.

“We are especially pleased to be able to host this important exhibit throughout Black History Month,” adds Stamford Campus director Terrence Cheng.

The exhibition “Still Separate – Still Unequal” seeks to examine ongoing racial and economic disparity in the U.S. public school system. Reports in 2014 – the year that marked the 60th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision declaring segregated schools to be unconstitutional – showed an increase in school segregation. The exhibition questions how this has happened, and how we can use art to push the conversation into the public discourse in a new and provocative way.

The exhibit “is a necessary platform to explore the complexities of race and class as it relates to our public school system,” says Larry Ossei-Mensah, co-curator. “Education is an issue that affects everyone, and in this current climate it is imperative that we utilize the power of art and history to foster a necessary dialogue for social change.”

Here’s what the artists have to say about their works:

Damien Davis

These four large plexi works are inspired by interviews with my mother, Delores Davis. My mother was one of the first students to integrate the all-white Crowley High School in her hometown of Crowley, Louisiana. She attended a historically black college – Grambling University – and then worked as a high school teacher for 30 years, before retiring recently.

The smaller plexi pieces directly below the larger works include text from the interviews. My mother chronicles her experiences going to a predominantly white school in the 1970s, her college education, and her experiences as a teacher.

These pieces reflect my interest in how lines can be used both aesthetically and conceptually to divide and connect ideas, while also having the potential to encircle and diagram even broader ones.

Uraline Septembre Hager

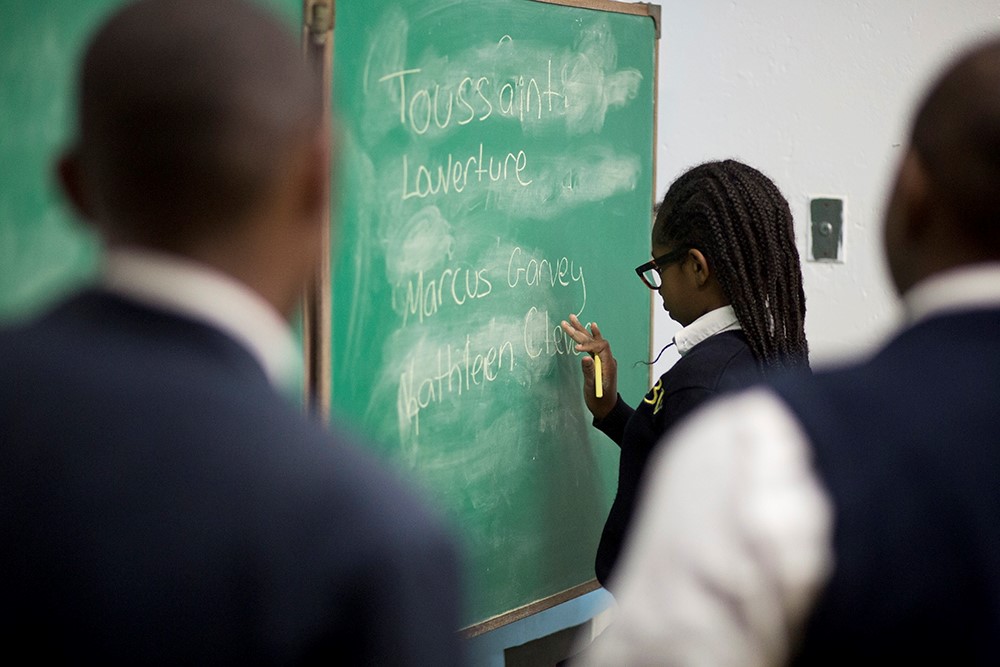

“Like Feeding a Dog His Own Tail” is an installation composed of a 6’ x 8’ model classroom containing a classic 1950s student desk, a chalkboard, a composition notebook, and No. 2 pencils. The piece is informed by my work as a middle school special education teacher in New York City, and observing the criminalization of our youth within the school environment. To enclose this classroom built for one, I have constructed a black fence that mimics both the bars of a prison cell and the fences that often surround schools and playgrounds. Conceptually, this work is inspired by my fascination with the dual purpose of fences: Depending on which side of the fence you stand, fences can serve to protect or exclude. “Like Feeding a Dog His Own Tail” invites the viewer to think about and question the links between America’s urban public education system and America’s mass incarceration system.

L. Kasimu Harris

War on the Benighted is a narrative constructed reality series about students who became frustrated with the inequalities in education; they rose up and began a quest to educate themselves. The story commences after each student’s response to a dearth of educational possibilities. Their grievances were with the school-to-prison pipeline, emphasis on standardized testing, and a diminishing arts curriculum.

Olalekan Jeyifous

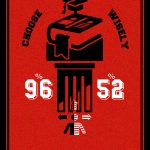

This work exploits the visual language of the High School Championship banner, a large tapestry which typically celebrates a school’s athletic triumphs. I have created a series of “anti-banners” that present a few startling statistics on the testing, policing, and incarceration of Black and Latino students.

The first banner, “The Examiners,” focuses on the illusion of choice given to Black and Latino students in under-performing neighborhood middle schools in New York City. Ostensibly, they are able to gain access to top-tier high schools within the city, if they score well on the state’s annual math and English test and maintain a high grade-point average. However as a result of socioeconomic status, school zoning, access, and opportunity, the students who gain admittance to the city’s best high schools continue to be disproportionately middle class and white or Asian. The 96 percent and 51 percent displayed on the banner refer to the graduation rates of the top-tier high schools and those of the most under-performing high schools in the city.

The second banner titled, “The Enforcers,” focuses through iconography on police presence in high schools, the criminalization of student misconduct, and disciplinary bias toward Black and Latino students. who are 3.5 times more likely to be suspended than White students for the same infractions.

In the final banner, “The Panopticons, the focus is on the effects of the practices and policies highlighted in the first two banners. The Panopticon, an institutional building designed in the late 18th century that enabled total surveillance of all inmates in a prison. The 70 percent displayed on the ribbon below refers to the percentage of Black and Latino students placed under in-school arrest, as well as the percentage of high school dropouts that end up incarcerated.

The backs of each banner, when viewed in sequence with one another, present a storyboard of a seated student raising his/her hand, a police officer running toward him/her, and then holding him/her in a choke-hold. This is in reference to the school-to-prison pipeline and the video that surfaced of a police officer body-slamming a black, female high school student.

jc lenochan

“Unfinished Business” and the “Melanin Chronicles” are subtitles for ongoing bodies of work with research-based content as the foundation for the works’ decolonization process.

“What you think matters, too,” a public drawing, derives from conversations about necessity and possibilities, in terms of our experience of class structures that we assume are democratic. When the very definition of democracy is the absence or disapproval of class distinction or privilege, the question is how do we subvert or expose these structures through social engagement, to empower through experience.

“What time you got?” is part of the process of deconstructing myths and biased concepts of cultures and subcultures in order to reconfigure/reconstruct them the way they could exist over time. In isolation, we have had conversations about justice that are both counterintuitive and counterproductive to real progress. How do we de-race a society that designed the very idea of class stratification as a prescribed existence?

“What my kids need to know by grade 4” is an ongoing project developed through the art of listening, which came about with fatherhood, when intentional listening became a question of can we listen enough? I share with students that we have two ears and one mouth for a reason, to listen twice as much as speak, but do we practice this? My daughter found this mini shopping cart and told me she wants it back after I finish making art with it. One day, she will fully realize that the “cart” is for her and has been hers from the start.

Carina Maye

The “Troubled Seat” and “Tools of Separation” series directs attention to the faceless student forced to participate in the American educational system. There are clear and intentional obstacles in place that obstruct the academic progress of students in the public education system. Today’s testing and curriculum design are not structured to holistically develop all students. This leaves one to question the future of these students and the life they will lead beyond the classroom. This exhibition provides a space for creative minds to critically analyze the current version of this passé system, which continues to afflict minorities. Such a platform reflects the idea that change cannot be made through this existing formula. It is proven that students are reduced for capital gains and exploited as test subjects during their matriculation. Examining the contentions minorities face in education and the organized techniques implemented by the defective structure to divide their students is the pivotal first step in a true call for reconstruction.

Shervone Neckles

“The Tales of Red Rag Rosie” blends surface with depth, past with present, real with imaginary, and serious with playful. Through the use of craft techniques – doll making, quilt making, and crocheting – the work attempts to identify the stories we choose to tell and those we choose to deny.

In “Blackboard,” Red Rag Rosie uses pictorial symbols, the earliest known form of writing, to retell the complex tale of slavery, subjugation, and the spirit of resistance.

Nicole Soto-Rodríguez

“Act # 3 Southwestern High School” is the third video in a series of four (the Abandonment Series) in which I explore the concept and experience of abandonment.

In my research for this series, I explored three possibilities that gave way to what later on became the video pieces. The exploration starts with site-specific choreographic exercises in which I take into consideration three aspects of abandonment. The intervention in the space, along with the choreography and the self-recorded and self-edited documentation, is what constitutes the video piece.

The history of the Southwestern High School building and the social reasons or consequences of it being abandoned today still resonate. The students who attended Southwestern were predominantly Latin America, and their families worked in the nearby Cadillac factory, which officially closed its doors in 1994 and during its peak employed an estimated 12,000 people. Families were forced to move to areas where there were available jobs.

What I hope to create is a way of sharing an experience with the spectator in which they can get a glimpse of a personal experience that I am making public. It is a call to sit down with the uncomfortable feeling of abandonment, and allow yourself to experience it and maybe be able to bear it.

Marvin Toure

This piece details the experiences of my first and second year in my MFA Fine Arts program in New York City. As one of four black students admitted to a program that hadn’t seen black bodies for years prior, I examined the results of inherent bias in this “safe space.” Initially, I created a site-specific wall relief, in one of the main hallways, detailing statements that classmates, professors, visiting artists, alumni, etc. made to me in the form of a blank crossword puzzle yet to be solved. The current newspaper iteration serves to retell my story.