In the wake of a major storm, like the one that battered the Connecticut shoreline in 2012, community resilience could depend on communication.

That’s the conclusion of a recently published report by UConn Department of Communication Professor Carolyn A. Lin in partnership with the Connecticut Institute for Resilience and Climate Adaptation (CIRCA) is the first of its kind to look at the social and psychological impacts of climate change mitigation strategies in two coastal communities hit hard by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. The study examines how Bridgeport and Fairfield residents handled the storm and the after-effects, and also how they are addressing plans to mitigate the impacts of future storms in their communities.

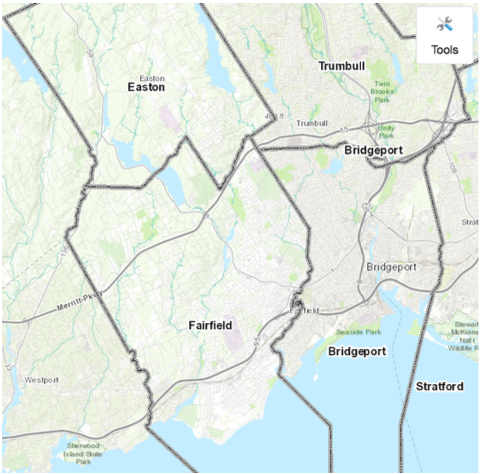

Fairfield and Bridgeport were chosen not only because they were impacted by Sandy, but also because they are very different demographically, explains Lin.

“Fairfield was hit very hard by Sandy and it tends to be more homogenous in terms of demographics. Bridgeport was also heavily impacted by Sandy and it is diverse and the largest city in Connecticut,” she says.

Soon after the storm, communities began the task of rebuilding, and Lin wanted to study elements of rebuilding and fortifying community resilience, particularly through the process of gaining consensus to make changes happen, and how those changes impact the community.

Lin used a mixed-methods approach, including focus groups and surveys, to evaluate how communities respond to recommendations and plans in the wake of storms. This in turn helped provide insight about shaping communication strategies to improve reception of those plans in motivating and engaging the community.

Residents and respondents included in the survey process all live within the same flood-prone areas; for instance, areas that were severely affected by Hurricane Sandy.

The report made clear that regardless of socioeconomic or demographic profile, residents in both cities share similar fear, anxiety, and vulnerability regarding the risks, says Lin.

A majority of the participants in the study noted the importance of science in planning for the resilience projects, and perhaps more importantly, they expressed a desire for effective communication from researchers and policy makers.

More respondents from Bridgeport suffered damage from flooding after Hurricane Sandy compared to Fairfield. However, Bridgeport respondents were two to three times more confident in their abilities to collaborate with other community members towards resilience and solutions, compared to Fairfield respondents.

“In Bridgeport the community has been engaged as part of the ongoing Resilient Bridgeport Project,” explains Lin, and this could be a reason for the confidence in the Bridgeport community.

Building resilient communities starts with engagement and a communication strategy. Lin recommends establishing a sense of community through openness, discourse, sharing of values, and instilling an assurance of accountability. This is an empowering and necessary component, says Lin, in teaching collaborative communication skills and showing community members that their actions matter. How to go about this differs with every community, though.

“One thing that I learned from this experience is that community engagement is not an easy task, which is nothing new, but there is so much we can do to improve the approach,” says Lin. “Trust is a really important element. If the community trusts you, you can help the community develop strategies to bring people together.”

Communities are as unique as the individuals that compose them, and so a one-size-fits-all approach is not the solution to build social resilience. The first challenge that needs to be met is to find common ground and establish a shared vision to get the community on board with resiliency plans.

“Having either researchers or teachers who have a really firm understanding of how a community functions and knows how to communicate is crucial,” Lin says. “Communications is much more than just talking. You have to understand how the community is thinking and feeling.”

Though the study yielded plenty of valuable data, Lin notes the report is published for public consumption in helping shape communication plans, but as a researcher it is only a first step.

“I will analyze the data in more depth and really dig into some of the theoretical elements,” she says. “My future publications based on this research will be more explanatory and delve into the human psychology behind the data.”

In the meantime, each day seems to bring reports of the accelerated pace of climate change, and science communication is becoming an increasingly important area of study, says Lin.

“Media plays a huge role in this in terms of influencing public opinion. Corporations could also do a lot of good if they were encouraged to do so,” Lin says. “News media now has a problem where their authenticity is questioned. This is a big problem.”

The report is clear that there needs to be a way to effectively communicate the data to the public, and that this communication needs to be taken under careful consideration to ensure it is effective.

“We need to help people understand that this one issue impacts so many other things, things which impact everyone every day,” says Lin, “Much of the effort has to come from the community itself.”

This project was funded by the Connecticut Institute for Resilience and Climate Adaptation.