Although the classic popular culture image of science involves people in white coats surrounded by bubbling beakers and flaming Bunsen burners, not all scientific experiments take place in labs. For many researchers studying global warming, the field is their laboratory, a situation that presents plenty of challenges.

For example: studying the way steadily warmer temperatures may affect the way species interact in a particular ecosystem. In a laboratory, experiments can be designed while taking for granted things like a steady supply of electricity and a ready source of materials. But what about experiments in the very ecosystem being studied?

That question now has an answer, thanks to a team of researchers who recently published how they were able to tackle the problem in the journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution. The team, which includes UConn Ecology and Evolutionary Biology researchers Christina Baer and Carlos Robledo-Garcia and Diego Dierick from the University of Costa Rica, devised a way to build portable heaters for experiments in microhabitats, and have made the details completely open-source so this type of equipment is accessible to researchers everywhere.

“I’ve been doing research in the tropics for a while and as that was happening, I was realizing that climate change was having easily observable effects on this ecosystem. I wanted to be able to study that better and try to figure out what is going to happen next,” says Baer. “This is, of course, a very complicated question.”

Baer explains that one of the ways to approach this research is to heat up microhabitats and track how they change.

“That gives you at least some idea of which animals are in a better place already to deal with warming temperatures and which are already in their upper limit in terms of the temperatures they can deal with.”

To better understand these limits, consider the difference between Connecticut, with its cold winters and hot summers, and the tropics, where temperature fluctuates far less throughout the year. Baer says that even in summer, the temperatures in Costa Rica stay pleasant, whereas those in Connecticut may be much higher. Temperatures in the tropics do not typically see extreme seasonal fluxes and that could be bad news for tropical ecosystems.

“Down in the tropics, it is like living in the perfect climate-controlled place year-round,” Baer says. “One of the things we are worried about is that tropical animals and plants may not have flexibility when it comes to temperature change. One of the ways to find out if that is the case is to do these kinds of experiments.”

Luckily, Baer tends to study insect communities, so the area that needs to be heated is not as large if she were studying larger creatures like lizards or monkeys.

“Basically what you are trying to do is put a heater around a bunch of interacting animals without interfering with how they interact with each other, [and] without also having the heat source be so big and complicated that you have to spend a lot of money on the whole thing,” she says.

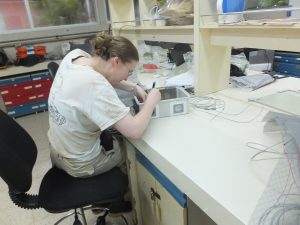

To simplify the process, Baer and her co-authors created portable heaters by weaving heat-emitting wire through window screen mesh. The result is a light and flexible heater that can be formed into any shape needed.

The heaters can be powered by car batteries, but for the initial studies with this design Baer says they were lucky to be working at La Selva Research Station in Costa Rica, which has electricity readily available. The heaters can be programmed, and will adjust based on the ambient temperature. For the initial experiments, the heaters were able to heat the microhabitat by about 2.5°C, which Baer says happens to be right about in the middle of expected temperature increases in Costa Rica by 2100.

For researchers who work in the field, having experience with “MacGyvering” equipment can be a vital skillset, and is often the difference between performing the research and not getting it done. Baer says these skills were ones she was interested in getting into her toolkit, and is happy to share this information with the world.

All the information on how to construct the heaters and program them have been made available on GitHub. This is a very important point, says Baer, who hopes open-source information like this will help make this much-needed research more accessible to people all over the world.

“Sometimes, depending on what country you are in, getting specialized scientific equipment can be more expensive than in the US because of import and custom taxes, for example,” Baer says. “The more people that can have the option of building their own stuff and having tools that don’t require big resources or infrastructure will mean more people can do these experiments. We definitely need more people doing this work.”

This work was funded by a grant from the Center of Biological Risk at the University of Connecticut and funds from the NSF LSAMP REU for U.S. Underrepresented Minority Students Summer Program in Costa Rica.